It is rare to find a movie that gloriously and unapologetically seeks to engender a feel good vibe so infectious you are tempted to dance, or at the very least sashay, like a member of a 60s female soul group, out of the theatre at the end of it, but that also seeks to make a political statement of some kind.

Wayne Blair’s The Sapphires manages to do just that, and then some.

It evokes the heady spirit of the 60s, when the strictures of conservative 1950s society were cast aside by the flower power generation, suddenly making, at least at first glance, anything possible.

But at the same time, it is careful to remind people that it was also a period when Australia’s indigenous population were still treated as second-class citizens having only obtained the right to be officially counted as part of Australia’s population in 1967, and were constrained by a status that held them back from fully participating in the full gamut of Australian life.

The Sapphires doesn’t shirk from conveying the kind of racism, both implicit, and horrifyingly explicit (the scene in the pub where the girls perform in a talent contest graphically illustrates some of the forces at work in the country at the time), and the way in which white Australia sought to either expunge indigenous people from the mainstream by consigning them to far way missions, or via the forced removal of children from their families during the Stolen generation period ( a fate which befalls one of the girls, which is told in a terrifying flashback sequence), integrate them into it so that they effectively vanish as a distinct people group anyway.

But its real power, apart from the music that binds the lives of everyone in it together in ways too powerful for even prejudice to counteract, is that it shows the way in which certain people decided to stand up against these odious attempts to treat as less than full citizens of the country, and claim what they believed was their birthright through sheer force of will and determination.

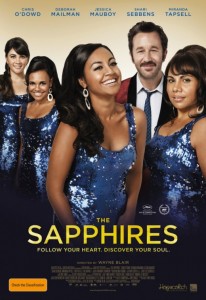

And sisters Gail (Deborah Mailman), Diana (Jessica Mauboy) and Cynthia (Miranda Tapsell) and their estranged cousin Kay (Shari Sebbens) have this defiance in abundance.

It propels far beyond the small world designated for them by an outside world that thinks they should know their place in society and meekly and thankfully stay in it.

This unwillingness to accept that they can’t realise their dreams their dreams of singing together in wider society, takes them, via the hand of “music promoter” (his claims to the title are dubious at best; his deep love of Soul music is not) Dave Lovelace (Chris O’Dowd, IT Crowd) who they meet the aforementioned pub, from the obscurity of Cummeragunja Mission in rural Australia to the relative bright lights and big cities of Vietnam during the war.

At its heart then, the movie is a love letter to the notion that you can rise above the limitations imposed upon you by social mores or economic circumstances – an issue just as relevant today was it was in 1968 when we first meet the girls – a notion it triumphantly celebrates all the way through its running time.

But it dovetails all this social commentary and quest for a better life by four young indigenous women, and yes one very lost white man, so neatly into this foot-stomping, Soul-harmonising romp through the momentous changes of the period (deftly summed up in a news montage near the start of the film) that it becomes one beautifully told story of self-realisation via the power of music, rather than the split-personality movie it could so easily have been.

Yes there are a few overly convenient plot shortcuts – the girls go from being deeply antagonistic to, and suspicious of Dave Lovelace, the man compering the pub talent quest, where the racism of the white drinkers is raw and blindingly evident, to convincing him to take them to the auditions for entertaining the troops in Vietnam in about 5 minutes flat, and Dave convinces the girls’ sceptical parents in even less time – they are necessary to get these siblings speedily to where they need to be.

And some of the dramatic moments feel curiously stunted, cut off just as they are beginning to summon a decent head of steam – Deborah Mailman excels even so as the emotional heart and soul, or the “mama bear” as Lovelace calls her during one heartfelt moment, and pulls together more than one scene that without her would have been far less than it ended up being; her chemistry with the cheeky O’Dowd too is as perfect as you’ll get in any movie – and this does rob the movie of some of its great moments of gravitas.

(image via spotlightreport.net)

However, as their glorious adventure through the new sights and sounds of a land far removed from their own descends into the hell of war, and everyone is forced to assess what they mean to each other – which triggers a more than believable reconciliation between Gail and Kay, who was removed from the mission as a young girl due to her mixed race parentage, an act which left Gail feeling guilty and resentful – the drama is pitch perfect and evokes, without flinching, the nightmare of being in a warzone.

Yes it is a feel good movie, which luxuriates in the deeply felt Soul music of the period, which Lovelace points out in a humourous moment is all about fighting back when life does you wrong, and the blissfully beautiful harmonies of the four young women.

But it is also a tale of coming of age, of the deep importance of family and the land, of the deep injustices unfairly visited on certain groups in society, and the fact that no one should ever simply accept their lot in life, no matter how great the oppression arrayed against them, if they have within themselves the power to bring about change.