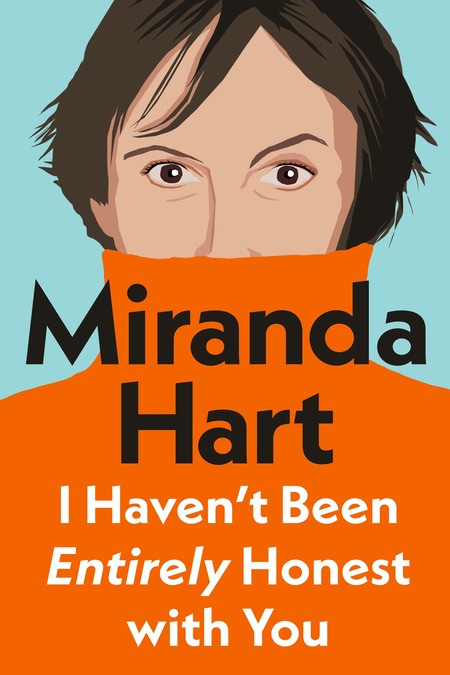

(courtesy Penguin Books Australia)

Miranda Hart, known for her whimsy and goofy good humour, would like us all to get a little serious for a moment.

Or perhaps a lot, and you can trust her, it’s for a very good reason, one which came to define her life in ways the self-admitted highly ambitious actor and comedian and endless whirl of activity never really saw coming when she collapsed in her home one way, too exhausted to even pick herself up from the floor at first.

She talks about what happened in that transformative moment and well beyond in I Haven’t Been Entirely Honest With You, which details a rich journey of physical, emotional and existential healing which is delivered with her trademark wit and funny asides but with a firm eye on the fact that sometimes the obvious thing is necessarily the whole, quite serious, story.

Referring to those who pick up this bright and breezy but deeply impactful book as “My Dear Reader Chum aka MDRC”, Hart talks about what it is like to find your life collapse into seeming nothing as your body seems to betray and rob you of everything you valued and held dear and which had powered you through a charmed life and highly successful career.

But, she asks, and asks with equal amounts of hilarity and searing thoughtfulness, was she in fact robbed or was she, as she now realises, given an unexpected opportunity to reevaluate who she is, what she wants from life and where it all should be heeded?

To conclude the heavy revvy (heavy revelation) of this treasure: if we hide our feelings to fit in and be loved as a little child, that’s initially a very clever way to find security, but ultimately, if we take that into adulthood, then we remain living in a subconscious pattern of fear … the “ists” reassured me that we can dismantle the old unhelpful patterns. Yay and phew! (P. 119)

If that all sounds like it might be a tad more serious than her usual stand-up routine or episodes of her much-loved, gleefully fourth-wall breaking sitcom Miranda, then you are right – it is way more serious than you’re used to from this beloved figure.

But by baring her soul, and that’s all thank you fellow MDRCs, Hart gifts us with a book that reads lie the sort of self-help instructional manual that those of us who can’t stand the earnest tweeness of the usual members of the genre have needed all along even if we didn’t realise it.

Drawing on an extensive range of courses, all “ists” – specialists of one kind or another who helped her chart a way forward through a wholly unknown and often distressing if illuminating landscape of the body, heart and mind – Hart dismisses the usual options for modern-day healing as not telling the full and complete story we all need to hear.

She doesn’t at any point poo-poo any of the usual remedies, acknowledging that for some people thy are necessary and effective, but what she does do is reframe everything into highly relatable ways which will resonate with anyone who has found themselves desperately ill or burnt out or simply out of answers in a world that expects us to push onwards, ever onwards, no matter how exhausted we feel, and without a word of complaint or interrogation of we are really feeling or what we actually need.

If you are someone like this reviewer who had reached a particular point in life, and it’s all there in the titular hashtag should you care to glance upwards in the post, and found yourself exhausted beyond all measure, you will find a lot to like in I Haven’t Been Entirely Honest With You.

Here at last is someone, speaking honestly and accessibly and with great and reassuring good humour at times, about what it means to do life.

And her answers, corralled from a wealth of experts and her own hard-won lived experience, actually speak to you because she zeroes in with unerring accuracy on the fact that all of us have been trained to approach life like some sort of high achievement oriented, society-wide popularity contest which actually does no favours to our overall sense of well-being.

I Haven’t Been Entirely Honest With You centres around “treasures”, insights which Hart says, transformed how she sees herself and life overall, and which recognise the close relationship between what we think and feel and the state of our physical being.

Hart posits, and it certainly rings true for this reviewer, that to live well means living authentically and saying what we mean and think – not in cruelly militant ways; rather simply dropping the politeness and the apologies in favour of being caringly honest with ourselves and others – to trusting we are loved and to silence the bleakly carping inner critics who treat us as an adversary and not as an ally.

Being productive, doing what needs to be done, nurturing our skills are all brilliant and necessary things – I am often at my happiest at work – but it’s the pace, MDRC. The way we do things, the expectation, the striving, the working conditions.* (P. 311)

Encouraging us to be “weird and wonky works in progress”, Hart wants all of us to be comfortable in our own skin, something which was a revelation to her but which also caught this reviewer by surprise some years earlier when he began to discover that he couldn’t sustain the life he’d been taught to live, one borne of people pleasing and false outward behaviour which was slowly and exhaustingly draining the life force from him.

Hart maintains in I Haven’t Been Entirely Honest With You that none of us can ultimately sustain a life lived so full-on on such unrelenting, unforgiving bases, and that what’s ailing us, and what ailed her, was trying to do in defiance of that still, small voice within us that says we simply can’t do this anymore.

Realising her life as she’d lived it wasn’t sustainable anymore was a shock to Hart and often a distressing one at times, but ultimately it was a good thing as the darling of goody British comedy came to realise that being honest with yourself and others might just be the best thing you ever do for yourself.

The brilliance of I Haven’t Been Entirely Honest With You is that it takes the sort of subject matter many of us instinctively shy away from because it all seems so superficially serious and introspectively wanky, and makes it relatable in a way that rings all kinds of recognisable bells – we know ourselves better than we think we do too says the author, and she’s right – and which might ultimately, if we live out, to lives far better than the ones we lives now.

It’s worth a thought fellow MDRCs – who knows where it might all lead?