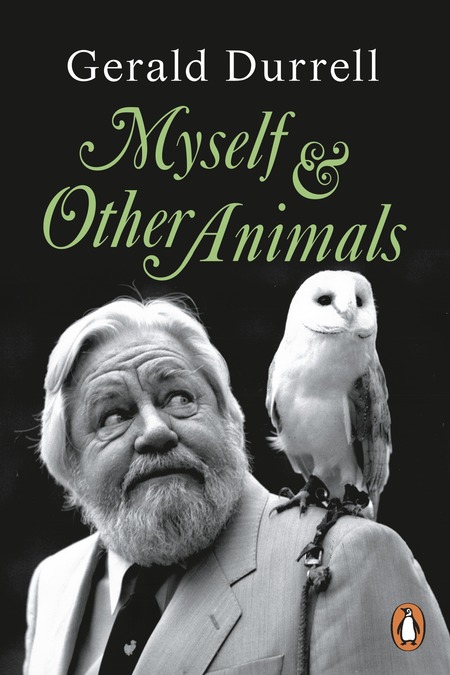

(courtesy Penguin Books Australia)

As part of my 60th birthday celebrations, I am highlighting figures and characters and franchises which have meant the world to me, enriching my life beyond measure and granting the ability to see this amazing world of ours in ways that might otherwise have evaded me.

In a life full of wondrously good and endlessly enriching reading experiences, perhaps one of the greatest discoveries were the books of British naturalist, writer and conservationist, Gerald Durrell.

A contemporary of Sir David Attenborough and possessed of a similar awe of and need to conserve the amazing natural world around us, Gerald Durrell spoke to something within me when I began to read his books as a boy, spending precious pocket money, well spent so I believed, on books that talked of the need to preserve the forests and savannahs and oceans and everything that lived in, on and around them.

Sadly Gerald passed away in 1995, but not before writing 37 books, starting the Jersey Zoo in the Channel Islands, training an army of conservationists from around the world and undertaking successful captive breeding efforts for over 100 species to date.

While his brother Lawrence is regarded as the serious literary figure, Gerald was clearly possessed of an amazing writing talent, turning descriptive passages into works on exquisitely beautiful art and bringing the natural world alive so vividly it was as if I could see it right in front of me.

Gradually the magic of the island settled over us as gently and clingingly as pollen. Each day had a tranquility, a timelessness about it, so that you wished it would never end. But then the dark skin of night would peel off and there would be a fresh day waiting for us, glossy and colourful as a child’s transfer and with the same tinge of unreality. (P. 32)

In an age when there was no internet, and you couldn’t simply look up a place or an animal or plant – that took a trip to the library, assuming, of course, said institution had a book on the topic (thankfully our small council was brilliantly well stocked) – Gerald’s ability to conjure up time and place, to make the unseen feel seen was a true gift, not to mention essential since the works were his chief means, fundraising aside, of supporting the vital work he was undertaking.

In honour of what would have been the esteemed naturalist’s 100th birthday, the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, and chiefly, his wife Lee, a talented and naturalist in her own right, put together Myself & Other Animals, a wonderful collection of specially chosen excerpts of Durrell’s writing from his many books, but also including tidbits from an unpublished autobiography, letters and observations by Lee herself on what drove her husband to do what he so successfully did.

Reading Myself & Other Animals, which had sat on my shelf for this special month of celebrations, I was taken right back to not only how much I loved Gerald and his incandescently good writing but how much he stoked a love of the natural world in me and how his words still carry so much weight today in a world that still sadly seems hellbent on destroying itself.

It would all too easy to simply harangue people for the hash they are making of the natural world, and while Gerald undoubtedly did that, he also rather wonderfully did much to spur people on to positive action by simply making the natural world not seem like something removed from us but as a vital part of who we are as indeed it is.

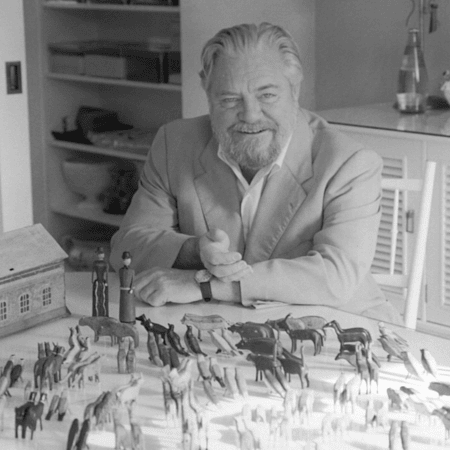

(courtesy official Jersey Zoo Instagram)

One of the great joys of Myself & Other Animals is that it takes you, more or less chronologically, thought often thematically too, through Gerald’s life.

We start at the literal beginning with Gerald’s birth in Jamshedpur, India, his childhood which took place, in part, in Corfu in the four years leading up to the start of World War Two, and his life following a blissful childhood where, while he may not have excelled in school in the traditional sense, he developed a lifelong love of the natural world which made such a difference world to its enduring longevity, beleaguered though it may be, and which transformed this reviewer’s life for the better.

Diving into Myself & Other Animals, I was reminded once again about enthusiasm for what you love can be so transformatively contagious.

While granted I have not gone on to save a species of animals or undertake a successful campaign on their behalf, Gerald’s fervent advocacy of the natural world has spurred me on to do what I can, in my small way, to change the world for the better.

Having had that influence at such a young age, made such a difference to me because I didn’t simply see the world as something to be used and exploited but as something to be treasured and preserved, a perspective which has meant I have approached all kinds of things differently to how I might otherwise have done.

Madagascar is one of those parts of our planet that any self-respecting scientist would be overjoyed to find one Christmas morning that Santa Claus had put into his stocking, because it would not matter if his interests were primarily zoological, botanical, anthropological or geological, for this great island – the fourth largest in the world – could be called, scientifically speaking, a multi-purpose present. (P. 190)

Has that meant I changed the world? Sadly, no.

But it has meant is that I champion those who are and I do what I can by recycling (regardless of the deficiencies of the system, it’s better than nothing) and water conservation and anything else, however minor, that falls within my agency to do so.

The importance of people like Gerald Durrell becomes abundantly clear in books like Myself & Other Animals which is far from just a love letter to a great mean, though it is definitely that, but rather a clarion call to people wrapped up in getting and having more, no matter the effect on the natural world, to look around them and weigh up everything they do and consider whether there is more they can do to lessen their impact on a planet that badly needs to be cut a break.

Or a thousand of them.

Gerald Durrell is one of the people who has changed my life for the better, enriching me with his wondrously evocative writing, inspiring me with a love of the natural world which is with me still, and motivating me to do my small part to counter the unthinking hell humanity is unleashing on planet earth.

Perhaps you could deride the efforts of one man in one city in one country as worth not much at all, but the actions of millions, and hopefully tens of millions of people like me can have a profound outcome and it’s no doubt something Gerald would champion, much as he does in the brilliantly good celebration of his life’s work, Myself & Other Animals, which will go on, we can only hope, to inspire future generations to fight the good work and made a difference where they can.

You can support the work of Gerald Durrell and the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust by heading to durrell.org