Grief, though intimately personal, can often feel like a very public weapon of mass disruption.

As the searing loss of saying goodbye to someone, or not in some cases with the grief more for what’s lost than whom, ripples out in an every-widening wave, families, friendship groups and communities can find themselves rent asunder, to greater or lesser degrees.

There is something bizarrely liberating about grief; in its messy, chaotic aftermath, people seem to feel free to say or feel all those things that have long been hidden, whether out of fear, a sense of misguided propriety or a weariness at the horror of revisiting traumatic events long past.

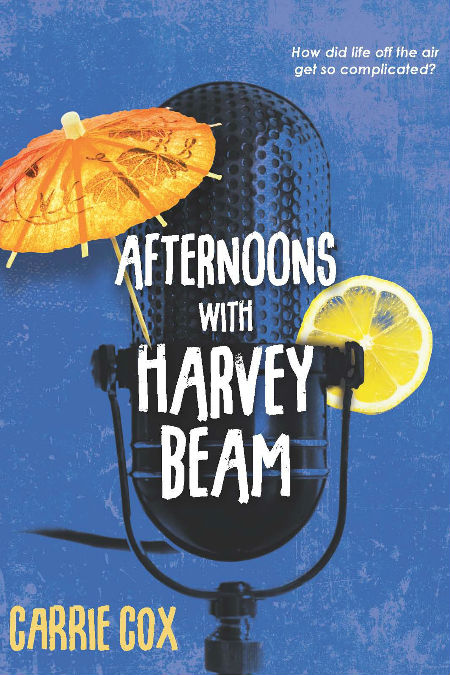

That’s pretty much how Harvey Beam, high-profile Sydney radio talkback host, half-competent dad and divorced man, finds it when he goes back to his hometown of Shorton in Carrie Cox’s beautifully-realised debut novel Afternoons with Harvey Beam to see his cancer-stricken dad one last time before he dies.

Of course, nothing plays out quite as nicely as that summation of grief’s mob rule-like effect would have to believe; in fact, while the disruption is most acutely there, and everyone is painfully aware of its status quo-trashing potential, no one really has the energy to fully give into the impulse to let it all hang out.

Not, it must be said, that they’re not tempted.

“And Harvey is taken aback by this. Because as long as he can remember, no-one has ever ventured an appraisal of Harvey’s relationship with his father that found Lionel lacking in any way. The conclusion has always been that Lionel simply is what he is, a man with his mind on other eons, and that perhaps expectations are patently too high or unfair.” (P. 77)

After all, the Beams are hardly Hallmark’s Family of the Week.

Split apart quite some years back when Lionel, newly-enamoured of tertiary-studying and the history of which he was so fond, gave everything to his studious pursuits and precious little to his long-suffering wife Lynn or his four children, Bryan, Harvey, Penny and Naomi, before abandoning everyone but Bryan (who was picked by Lionel to live with him in a weird familial Hunger Games that left Harvey devastated) and leaving home.

In the succeeding years, the relationship between Penny and Naomi, both still resident in Shorton and married with kids, has developed into a feud that only abates briefly during Lionel’s tense funeral and wake, Harvey has absented himself to faraway Sydney where his ex-wife Suze and teenage daughters Cate and Jayne live, and Bryan has taken up the mantle of his father’s successor in temperament, career and academic pursuit (though it is hinted this may be a result of some sort of Stockholm Syndrome as much as devotion).

Lynn is living with Naomi to help her with the kids, but that’s as close as this family gets, with only Harvey and Penny enjoying any real kind of closeness.

So there’s a lot of stuff brewing just below the surface, the reality and knowledge of which fills Harvey with sickening dread as his plane touches down at Shorton airport, with the only bright spot being a spark that seems to have been lit between Shorton’s famous prodigal son and a locum nurse named Grace.

The impressive thing about Cox’s writing, which is endlessly clever and luminously descriptive, is how she restrains herself from simply letting Afternoons with Harvey Beam descend into some sort of slapstick, vitriolic black comedy, which in lesser hands it could so easily have been.

In this case, less is most definitely more, and as we experience events from Harvey’s jaded perspective – the refreshing thing is he’s not some disillusioned, unredeemable cynic that becomes insufferable to spend time with; he is simply a fallible likeable human being whose life has not exactly played out as planned … Et tu, Brute? – we come to see just how much has gone wrong in the Beam family and explore whether it is really worth upending the familial apple cart to sort it all out.

As the wait for Lionel’s inevitable death grinds on, and Harvey, who was abused constantly by his father in a way none of the other siblings were, grapples with whether he is even sad his father is passing, we come to appreciate in ways large and small, resigned and liberating, that there are some things, many things possibly, that simply can’t be fixed.

Sure, you could have it all out in a blisteringly incendiary back-and-forth between family members, but really, realise Harvey in one of the many incremental moments of clarity that punctuate his time in Shorton pre and post Lionel’s death, would that gain?

“He glances toward the back of the church (no sign of Grace) and then turns his attention to the priest, a man in his early seventies at best, shiny face sprouting from a swathe of heavy cloth and sashes. He is looking out over the congregation, an ambitious term for this lot, Harvey thinks, and unmistakably the man looks disappointed. Surely he must see, on days like this, a collection of disconnected people for whom religion is just scaffolding for major life events, nothing more.” (P. 186)

Would it erase all the hurt and estrangement? Would it suddenly make Lionel like his son? None of that would come to pass, and so instead we see Harvey, who finds unexpected connections where there were none before with likes of his brother-in-law Matt and his daughter Cate, come to some sort of imperfect peace about the fact that life, especially in the emotional battleground that is many families, is, as Naomi is wont to say, what it is.

Harvey and his sister Penny hate the phrase, but in the end, there is a truth to it that Harvey has to admit to; for all the pain and loss a person may cause, and Lionel was responsible for more than his fair share, no amount of grief-fuelled slinging can fix that.

That’s not to say there can’t be moments of absolution, clarity and explanation and certainly they come via Lynn, Matt and Penny most notably, nor that you shouldn’t seek to heal old wounds, but as Cox sagely notes again and again in a gloriously well-nuanced tale, sometimes that’s not possible and you simply have to make your peace with it.

Ringing with exquisitely-rendered phrases that sing and startle with their originality and insight, Afternoons with Harvey Beam fairly brims with a gently-expressed but no less penetrating for that understanding of family dynamics that may help many people to come to grips with the less than ideal circumstances of their own lives.

We’d all like that magical moment of closure at the time of someone’s passing, particularly someone with whom relations were less than ideal and possibly downright nasty, but we may not always get, and Afternoons with Harvey Beam beautifully explores with compassion, honesty and good humour (and deliciosuly good writing; did I mention that?) what happens in the netherlands of grief when you realise the hoped-for happily-ever-after will never come your way.