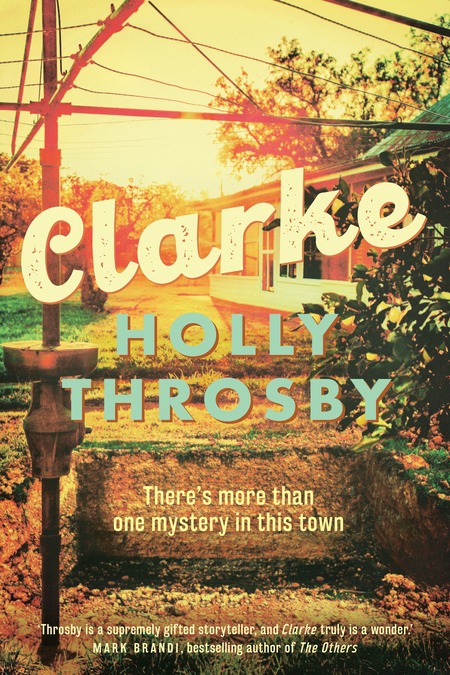

(courtesy Allen & Unwin Book Publishers)

Connection is the heart and soul of the human condition.

It gives us a sense of place and time and often identity, of feeling as we matter because we love and we are loved back; but for all the good things that come our way because we know and are known by others, there is also a great deal of pain, of loss, of aching uncertainty and dangling loose bloody threads of life unresolved and unexplained.

Someone who is intimately and achingly familiar with this is Leonie Wallace, a woman in her younger forties who lives in the town that gives Clarke by Holly Throsby its name, and who looks after four-year-old Joe, a boy whose mum is absent but who is curious and loved and sad and happy all at once.

Barney Clarke – his surname is a sheer coincidence and no, he is no relation to the town’s eponymous founders – is also all too concerned with the good and the bad of connectivity, having been both blessed by it with friends who stick around through the worst of his personal trauma and grievously injured by it to the very depths of his scarred and sorrowing soul.

These two vulnerable yet richly loved people form the emotional core of this remarkably affecting novel which offers up a story which is both a love letter to the connection that comes from small towns and a salient reflection on how the same things that bless you can’t just as easily strike you down.

‘She’s in there after all.’

‘Well, that’s what they must be thinking.’

‘I knew it, Dorrie,’ said Leonie, rippling with a sad sort of excitement. ‘We both did. We’ve always known she was in there.’

For all the sadness at the heart of Clarke, there is a great deal of hope and love and healing too.

As the novel opens, Barney’s backyard is being excavated by police who are looking for the body of Ginny Lawson, a woman who once lived in Barney’s now-rented home and who disappeared not long before her alleged abusive husband fled to Queensland where he found a new love and life.

Leonie is hopeful of many things as the home’s shed is torn down, its concrete base shredded and its earth exhumed – she wants justice for her close friend Ginny, as does her BFF neighbour, retired therapist Dorrie who along with her husband Clint, grieve what they suspect happened to Ginny six years earlier.

But Leonie also wants a sense of completion; she wants to know that the biggest question of her life – what happened to Ginny and where is she now? – can be answered and that her life, which has changed both for the better and the worst in recent years with the arrival of Joe and the searing grief that accompanied him, can move on without the pall of unexplained loss that has long hung over it.

Told with richly emotional and thoughtful nuanced quietude, Clarke is once of those richly realised novels that acknowledges the very worst that life can throw at us even as it embraces the salving idea that there is a way to come back from all that pain and loss and that it’s the same connection that delivered it in the first place.

(courtesy official author site)

Sitting at its heart, Leonie and Barney, two strangers who become friends as the police hopefully start to get to the bottom of a mystery that has long consumed more than a few people in the town, are characters who beat with the drumbeat of what it means to be human.

Brought to life with quiet intimacy by Throsby who has a real gift for saying big things in thoughtfully nuanced ways that are epically loud without ever raising their narrative voice, the lives of Leonie and Barney are proof that big, enormous things, both good and bad, do not happen in the grand blockbuster manner beloved by Hollywood but in the small folds of the everyday where we consigned blandness and nothingness, but where, if we’re paying attention, life actually happens.

There is a dance to the way in which Leonie and Barney get to know each other, their growing friendship proof that while being connected to others has caused them great pain, that it is responsible for a far stronger and greater sense of nourishment, support and love.

Far from being a cliched dollop of greeting card tweeness, Clarke gives these positive qualities grunt and heft and raw truthfulness, making it clear that while life can be bestial in its cruelty and the way it seems to inflict grief without so much as by your leave, it can also give us so much that making living more than worthwhile.

Barney cleared his throat and said, “Yes okay. Thank you, Leonie.’

She said, “What are neighbours for?’

It is this down-in-the-trenches, mud-and-guts lived experience that percolates all the way through Clarke which knows that while we lose a great deal on our journey through life, we are given much too.

The balance is never quite right and we always risk sliding towards more sadness than joy, but Clarke stands firm on the idea that for all the risk of things going awry, that we gain far more from being connected than we lose.

It’s that honest assessment of life’s equations and the push-and-pull nature of connection that brings so much joy to Clarke, a novel that feels like all of life has been poured into it but in a way that is accessible, truthful and honest, its rawness giving us comfort as some extraordinarily difficult things happen.

We might often think that things have to be out and loud and proud to really mean anything, but Clarke is proof positive that we exist in the whispers and the hopes and the quiet expressions of grief and healing, and the key to all of it is connection.

Picking up Clarke after its spent three years on a massively impenetrable TBR (to be read) pile is one of the best things this reviewer has ever done as he came to appreciate how devastatingly sad and endlessly unknowable life can be but also how rich and nourishing it can be if we let ourselves be known and know right back, all through one brave grieving woman, a young boy who wants to be loved after all kinds of pain and a man trying to figure where next in a world where the answer lies with those you know and the ways they point you forward to healing and new life if you let them.