If you have been paying attention to the world of late, wrapped up rather despairingly as it is in pandemic, war, climate change and creeping intolerance and extremism, it will not surprise you that hope is in short supply for many people.

How can it possibly assert itself in any meaningful fashion when anti-vaxxers and civil libertarians are decrying science and sound government advice as tools of authoritarian control, when democracies are under attack from Trumpist leaders who see facts as a malleable and all too easily discarded commodity and when the basic humanity seems to be disappearing from the face of the earth?

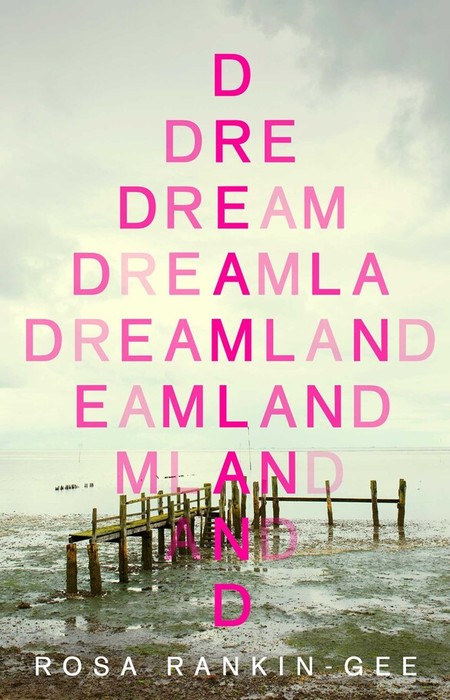

And yet in Rosa Rankin-Gee’s superbly gripping and deeply, emotionally resonant novel, Dreamland, where all of these disturbing trends have reached a nightmarishly definitive crescendo, when hope and the capacity for fierce unconditional love should have reached an irretrievable nadir, the ability to believe in better things to come is somehow still alive, and if not well, at least present and accounted for.

Make no mistake; Dreamland is not some Disney-esque fable where the very worst of things and time are dispatched with a snappy, sugary song, inspirational words and emboldened humanistic determination.

It is in many respects a bleak and sobering tale as Rankin-Gee explores the possible end point of government policies which reward the rich and punish the poor, the seemingly endless march of climate change as it lays waste to our planetary home, and the way in which many communities outside of major urban centres such as London (the novel is UK-set) are being used as dumping grounds for the poor and dispossessed.

“I don’t know. There are so many scenes, and most of them seem frozen now. My mum too — I’d freeze her right then if I could. After we got the news about her parents, she decided, she told us, to relax a little. Which meant go out more. There were nights when she came home with blood on her top, or no shoes on — with Liam, without him — but she was still just about on the edge of being okay then.

There were so many edges, edges everywhere. It’s just you never know where exactly the edge is until you tip over it.” (P. 46)

This march to an increasingly unjust society rife with social inequality and political extremism is documented through the eyes of Chance, a young girl-then-woman who has been brought to the fading coastal resort of Margate by her once middle class, now junkie mother who has a predilection for choosing the entirely wrong type of men.

Theirs is a world lives in tatty hostels and violent neighbourhoods, where school is sometimes open, sometimes not, where social programs start and stop with alarming regularity and where a hard scrabble is the default not the exeception.

All Chance, her elder brother to another father J.D. and her younger brother Blue have is sheer grit and determination, driven by a ceaseless need to survive, an impulse which not always rewarded and which comes up emptyhanded.

Even so, for all this bleakness, and the ominous presence of Chance’s mother’s abusive younger boyfriend Kole, Chance somehow keeps keeping on, driven largely by a need to love and protect Blue, but also by some innate sense that life, damaged and broken as it is, is worth fighting for.

Again Rankin-Gee does not gild this particularly lacklustre lily; rather, by being unstintingly honest about the challenged Chance faces in her daily struggle to survive, and yet how this impressive young woman gets up each day and tries to make things work, she beautifully brings to life the capacity of the human spirit to keep hope alive even in the most diabolical of circumstances.

The hope and love that Rankin-Gee celebrates throughout Dreamland, the world of which is as dystopian as you can get, feel incredibly muscular, real, and authentic.

It is proof that while these two qualities are often rendered as rose-tinted, heartwarmingly light and bright things, they are in fact incredibly robust and tenacious, as far from a sweet ditty in a cloying animated feature film as its possible to get.

With writing that is always entrancing and lyrically rich, Dreamland evokes how powerful hope can be.

In Chance’s day-to-day life, the hope she clings to may not have the power to move mountains necessarily – if it did, she would have long ago used it to alter her life beyond all current recognition – but it does have the power, most of the time at least to sustain Chance through a life full of abuse, deprivation, loss, death, economic collapse and manipulative cruelty.

She is also buoyed up by meeting Franky, a mysterious young woman who is clearly from outside of Margate, a Londoner Chance rightly guesses who has access to everything Chance does not, and who becomes a lifeline of love for a young woman whose experience of Cupid’s core commodity has been tainted at best, murderously ruinous at worst (save of course for Blue, her best friend Davey and her mother when she’s at her best).

“He sat with me for an hour. Fed me chocolate. Kept saying I was an idiot. I kept saying I was an idiot too, and that he was. I don’t know why we said that to each other so much all through our lives. Maybe because we both always knew we weren’t. Somehow he managed to make me laugh too. We both laughed. I can’t remember what about. Fear, euphoria — they’re weirdly close together sometimes.” (P. 298)

Franky’s arrival awakens something long lost, if it was ever present at all, in Chance, the sense that one person can unconditionally change your life and make it better in a way that a hundred broken-into homes cannot.

It is the twin sustainers of love and hope that help Chance to weather grief, disappointment and what effectively amounts to governmental genocide of its poorer citizens, and which given Dreamland such a rich, living quality, a tangible, palpable reminder that the human spirit can rise to immense challenges if given even half a chance.

There is nothing fairytale about this world, which finds itself evoked in writing that is both searingly serious and unexpectedly funny (how else do you deal with day-to-day disappointments without a heady sense of the ridiculous), and Rankin-Gee never once pretends otherwise; however, the weight of so much misery and extremist hellishness does not then preclude any sense of optimism, however tenuous, which finds expression in ways that will surprise and enthrall you.

If Dreamland is the future, and Rankin-Gee does make an alarming case for it being just that if current trends hold true, then many of us are in for a whole world of pain, especially those most at risk on society’s margins, but what’s important to note, and it finds buoyant liveliness in the person of Chance, is that even against something this nightmarish, hope and love might yet persist, testament if nothing else to the tenacity of the human spirit.