Love in our modern age has been reduced in many ways to an almosy infantile, fey semblance of its former vigorous self.

Where once love compelled great Shakespearian sonnets or set in motions the events that led to the Trojan War, it is now imprisoned in cutesy greeting card rhyming couplets or stuffed into movie-of-the-week love stories so treacly you’re not sure if you’re going to swoon or fall in a dibaetic coma.

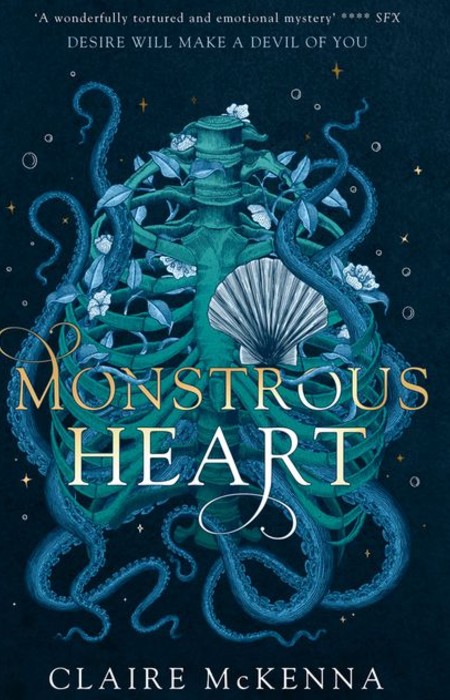

But in Monstrous Heart, Claire McKenna’s epic tale of fevered attraction, monsters and the fight to ensure your place in the world against near-impossible odds, love is an epic force, a seething, roiling beast of a thing that seizes you, demands from you and takes as much as it gives.

In this brilliantly-realised piece of vibrant gothic theatre, there is very little about life that sits calmly in teh background waiting to be noticed and this applies to love as much as anything as the newly-arrived Lightmistress of Vigil finds himself confronting forces far rougher, intense and gritty than any she knew back in her home city of Clay Portside where her family, by dint of their impressive blood talents, are aristrocracy, approved by the Eugenics Society to occupy a rarefied place in a tightly-hierarchical society.

The world of Monstrous Heart is invigoratingly, steam punk-y fantastical, a beguiling mix of 19th century technology and emerging 20th century wonders so that it is quite possible to have a sailing ship armed with sonar or a car driving along a windswept promontory where nothing has likely changed in centuries.

“I will be strong, she decided. I will be strong. So, the man had merely attempted to run her down with his boat like a coward. Let him be a coward now to her face. She had experienced worse manner of trials. A scar upon her throat remained from when a hapless dockside mutineer once took her as a hostage before taking his own life. She had worked the docks during the False Unionist war, the war of the Wharves, and the Battle of the tea Leaves. She had seen the worst of people.” (P. 82)

The worldbuilding is immaculate and immediately alive with the protagonist Arden Beacon moving between two countries, her home nation of Lyonne and her new far more rustic and salt-swept home of Vigil in Fiction, in such a way that both spring quietly but assuredly to life in ways that owe nothing to expositional drudgery.

Fiction in particular is a marvellous creation.

Seen as the backward companion to its more cilivised northern neighbour, the country to which Arden is assigned as a lighthouse flame keeper (she uses the magical qualities in her blood to sustain the flame which demands a bloody price each and every time it must be renewed) is full of intrigue, gossip and menace, with the nearest town to the now-isolated Arden described in terms of decay, oily encrustation and backward, gossip-laced mentalities.

This is not a world in which you treat lightly, not least because, as rumour has it, the monsters on land with two legs can be just as vicious and unsparing as the creatures such as plesiosaurs and krakken that fill the ocean depths.

In many ways, there is a violent, breathtaking majesty to Vigil and the offshore Sainted Isles whose name belies a place where the petroleum industry and xenophobic reign and where only the hardiest and most foolhardy of newcomers dare set foot.

In amongst a society as dark and untrusting as this one, controlled with ruthless authoritarian oversight by the Eugenics Society which assigns human value based solely on what flows in a person’s veins (or doesn’t; in Fiction, the blood gifts are rarely if ever acknowledged anymore), you must be a particularly noteworthy person to stand out.

Such a figure is Jonah Riven, an isolated man, both geographically and socially, who hunts the monsters of the deep but who is also rumoured to be quite monstrous himself, a man who murdered his wife and his family and who is best avoided where possible.

Alas, Arden, who is struggling with some fairly matters of her own, not least her teunous place in a mysogynist society and her own broken heart (and who experiences the relational best and violent worst of her new home), has no choice but to see and interact with Jonah, her neighbour on the isolated promintory on which the lighthouse sits.

The dance that develops between Arden and Jonah is a complicated and emotive one, and Monstrous Heart explores its fiendishly involved complications with a calm and oft-breathless insight that suggests there is far more at work than the simplistic perceptions of the townsfolk of Vigil have allowed for.

That is, of course, the great delight of this most gothic and human of novels.

Scene by scene, person by person and whispered morsel of gossip by bloodstained innuendo, Monstrous Heart builds a world and a story in which the great messy contradictory nature of human is both revealed in all its glory and scorned in its malignant blackheartedness.

For all its gothic majesty and gloom, the novel is primarily a story about the unremitting power and primacy of love, the way in which real robust love doesn’t linger on the edges and float on the periphery but storms in with furious certainty, propriety and small time concerns cast aside with passionate lack of concern.

“‘He was big. Angry too. Same I was angry when you bound me and bled me, no more than animal. What moral failing had you think hurting another fellow human was worth profit?'” (P. 305)

What captivates the most about Monstrous Heart is the way in which people like Arden and Jonah are forced to putside what they want the most in favour of what society or the world around them demands.

Neither are meekly compliant in this respect, and McKenna powerfully demonstrates how much they are their own people at every turn, but even so, they often have little choice but to comply with the forces pushing them onward or to fight back at great cost, with such a titanic battle taking much of the final act of this engrossing work.

There is so much invigorating passion and power in Monstrous Heart, but so much raw, affecting humanity too, and as the book builds and builds with ever more force and narrative intent, and the truth of things is revealed for both good and ill, it is this humanity which makes the greatest impression, with Arden and Jonah emerging as people who are far from the sum of their pasts or gifts or the cruel gossip that swirls around them.

McKenna manages to invest beautiful language and an often unassuming storyline with an intensity that creeps up on you, that seizes you in ways you don’t see coming and which transforms you every bit as much as its transform the two people at its heart.

Monstrous Heart is a gloriously fierce novel, one which addresses the very worst of the human condition even as it celebrates those qualities which can elevate us far above the gossip of the small-minded, the possessive destructiveness of the narcissistic and the violence and horrors of the expedient.

This is richly-imaginative, expansively-enthralling fantasy that doesn’t just combine 19th century puritan values with modern sensibilities; it goes far beyond that, telling a love story so massive, so passionate and all consuming that no one can be the same after reading it, if only because you realise it is possible to stand up to tyranny, to oppose those who would press you into tiny, suffocating conservatism, and to stand tall with love in front, behind and around you in ways that may not win all the battles in which you find yourself but which possess a power to change things far beyond anything you might expect.