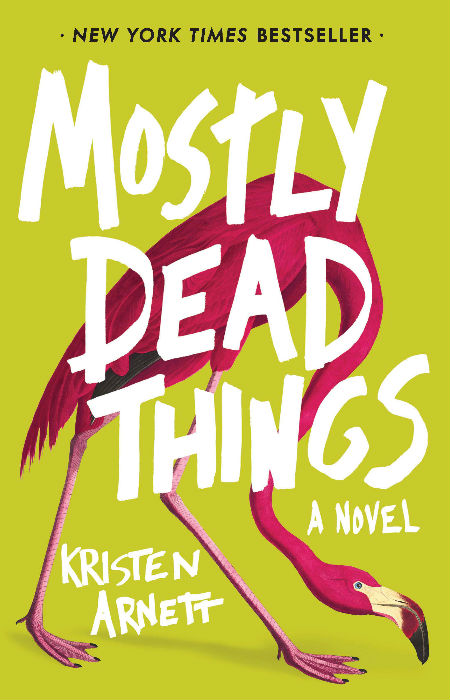

One of the great truisms of reading, indeed life itself it seems at times, is not judging a book by its cover.

However, it is well nigh impossible to pass by the boldly bright cover of Kristen Arnett’s Mostly Dead Things, a tale of messed up families, love and weirdly-expressed grief, without taking a good hard look at a book that pretty begs to be bought and read as quickly as humanly possible.

The good news is that the book itself is every bit as captivating as its alluring cover, written with real emotion, understanding and a queer sensibility that informs the protagonist Jessa-Lynn Morton with a richness you don’t often find in stories that veer from the heteronormative mainstream.

Truth be told, everyone else in the book is avowedly straight but Jessa-Lynn, complete with all the self-recognised tropes of her sexuality such as a penchant for wearing jeans, fixing things and getting a U-Haul loaded and ready to go after the first date (okay that last part is a work in progress, thanks to some crushingly big emotional intimacy issues) is a lesbian through and through, a lesbian, it should be added who is also a taxidermist in a small town in baking-hot central Florida.

She is also, as is the rest of her dysfunctional family, mired in the grief of the loss of her father who committed suicide a number of months earlier, leaving Jessa-Lynn, her brother Milo and her mother unmoored as never before.

“Then I went to the back and pulled out the mop bucket and the bleach, staring hard into the water as it churned up in the yellow tub. Told myself it was the fumes that teared me up as I dunked the mophead into the liquid, and then began the slow process of cleaning up the mess. I left the letter on the counter until I could get myself under control, wondering if it would say anything to help me understand the animal in front of me.” (P. 13)

If you think of grief as a bomb that slowly explodes through a family’s status quo, you get some idea of how Jessa-Lynn’s father’s passing affects a family who was teetering on the edge as it was.

Lost in a past that isn’t coming back, and failing, Jessa-Lynn belatedly realises, to get to truly know each other in a very painful present, the Mortons are flailing, unable to connect to each other or deal with their grief, a messy state of being that leads to some very amusingly painful outworkings.

Take Jessa-Lynn’s mum who has spent many years under the thumb of her husband whom she loved but who treated her, and his children, with the loving contempt of someone who always knew better, a man who took the precision and certainty of his beloved taxidermy and tried his best to apply it to a family who were nowhere as compliant or pliable as the dead animals for whom he crafted a narrative in which they had no real say (and spun off in their own protective orbits as a result).

His family, and especially his wife, were in much the same position, and so, after Jessa-Lynn makes contact with captivatingly mysterious local art gallery owner Lucinda Rex, who loves the taxidermied animals that fills the store in which alcoholic, emotionally-repressed Jessa-Lynn feels most at home, her mother seizes the chance to make art with her husband’s creations which push the boundaries of all kinds of good taste but which offer her a release long denied.

Jessa-Lynn doesn’t understand or dislike this aspect of her mother, as much as she can’t understand why her brother Milo, kind and caring but all-at-sea Milo, won’t be a better dad to son Bastien and daugher Lolee, but it eventually forces to confront her self-imposed remoteness from her family and a number of other life-limiting emotional choices she has made.

Such as being unable to fall in love with any other woman such as, oh, Lucinda, because she is still in mourning at the abrupt departure of her onetime best friend Brynn, who was the love of her life and her sexual partner over many, many years and yet who, craving stability and normalcy, married Milo until that emotional adventure came to an end.

If you’re beginning to appreciate that Mostly Dead Things is full of all kinds of gloriously twisted and dysfunctional family dynamics that are entertaining as they quirkily bizarre, you would be right.

However, fun though they are to read, these elements alone would not be enough to sustain a novel of sublime substance and emotional intelligence which Mostly Dead Things most certainly is.

Into the wacky and the strange, Arnett has deftly and affectingly inserted an intensely beautiful and highly-relatable exploration of grief, and the myriad ways it finds expression.

It’s tempting to think that grief has only one, easily-recognisable form but that’s not the case as anyone who has ever experienced it soul-scorching passage will intimately know, and it’s a lesson that Jessa-Lynn has to learn as she reassesses her opinions of the odd and unknown ways that her brother and mother are responding to her father’s sudden and unexpected death.

“I’d already gotten whaT I wanted from the peacocks. Every time I looked at them I felt bone-deep satisfaction, as if a burden has been lifted. I wondered if this was how my mother felt about her own art, a selfish pleasure from forcing the work to give her what she wanted. For a short moment I was filled with guilt, to consider depriving her of that wildly good feeling. Then I remembered the father figure on top of the water buffalo, pale face peeking from the patent leather mask. The gray, bristling mustache fixed about its motionless lip. There was nothing redeeming about it. I couldn’t allow it to live.” (P. 223)

Arnett, who offers up finely-etched characters whose dysfunction makes sense when you get to really know them and you do to a deeply-pleasing and engaging degree, invests the Mortons with some very down to earth human fallibility in the midst of their surface oddities.

They are, when you dig down, simply trying to process a world without the man who for years defined the style, flavour and emotional expression of their family.

With him gone, they have to renegotiate life and come up with new ways to navigate its many challenging paths, a journey that we see primarily from Jessa-Lynn’s vantage point as she grapples with moving from what you know and have always known and taken comfort in to a whole new ways of living that bears no easy resemblance to what’s gone before.

It’s a journey anyone lost in grief has to undertake and it is a credit to Arnett’s gift for not just emotionally-intuitive writing but some penetratingly affecting insights that you come, sadly, to the end of Mostly Dead Things, a whole lot wiser about what it might look like if you can just open yourself up and make your peace with a world you no longer recognise and your own battered self who has a lot of learning and changing to do if life is to mean anything again.