If you take a good hard look at love in the real world, it is far from the light, fluffy confection of romantic comedy legend.

Sure, that’s appealing and who doesn’t want to feel wafted along on Cupid’s lighter-than-air ministrations, but the reality is that love, real love, is muscular and gritty, able to handle all manner of calamities and problems and accepting and accommodating of a world of unexpected variables that it’s more confected cousin might struggle to encompass.

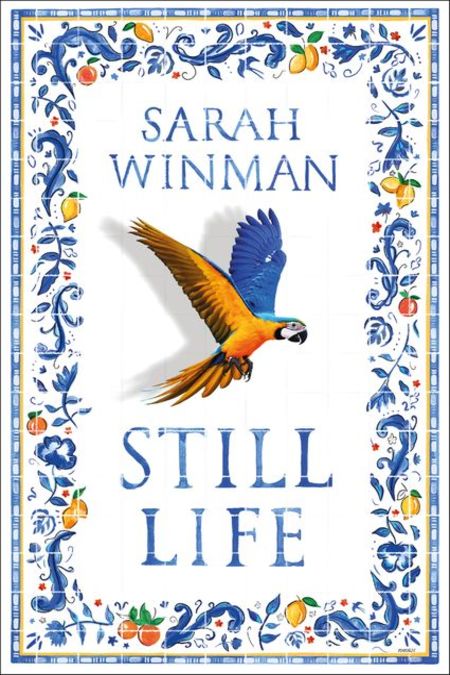

Still Life by Sarah Winman (A Year of Marvellous Ways, Tin Man) knows all about this dichotomy and more, offering up a wholly warm and rich story of love down in the trenches of life, literally so in the opening chapters set during the Allies’ liberation of Italy, and particularly Florence, in 1944, where you do not have the option of picking and choosing who and how you will love.

You just love and deal with all the consequences of that, however they manifest themselves.

Beginning with a chance meeting between English sexagenarian Evelyn Turner, a vivaciously witty, intelligent art historian and likely spy, and young British soldier Ulysses Temper (a perfect, utterly memorable protagonist name if ever there was one), who spend a memorable day together discussing life, art and the pursuit of beauty and the realness of life, Still Life is a vibrantly hopeful novel that holds high the idea that love is capable of far more than simple, overwhelming attraction (though, of course, that is very much woven into the fabric of this brilliantly told book).

“I was twenty-one, said Evelyn. Not that much younger than you, Ulysses. That was my first experience of Florence. Travelling unchaperoned and ready to fall in love.

And did you, Evelyn?

Evelyn paused as she tasted the wine. I did, as it happens, she said. Once with a person and once with the city itself. You have all that to come, Ulysses. Open your heart. Things happen there, if you let them. Wonderful things.” (P. 23)

Time and again, in situations where love might seem to be a stranger to the cold, hard hand of reality, it proves that it has the staying to overcome all manner of adversity, poor decision-making, brokenness, sadness and loss.

And in a novel that spans the years from 1944 to 1979, with a short trip back to the start of the twentieth century to tell the tale of one emotionally-resonant key character, there is a lot of darkness and terribleness for love to wrap it endlessly hopeful arms around.

The absolute, sheer, exhilarating, heart-uplifting beauty of Still Life is that is brutally honest about how awful things can be and how tough a road people have to travel but it never once says that you cannot be saved from the very worst things that can happen to you, especially when you are loved.

That might sound all fey and will-‘o-the-wispy but the truth is that love in its raw, true form is about as far from inconsequently light-as-air as you can get, and far more varied, queer and diverse than a narrowminded world is willing to admit.

Certainly when Ulysses returns to his working class part of London in the aftermath of World War Two to find much of what he knew, including his father’s globe-making business (save for the letter plates and one globe saved from the rubble by an older much-loved figure in the neighbourhood called Cress), and he realises he has a choice about the life he wants to live, love is the one, muscular guiding force that shapes all the subsequent, massively hearted storytelling that happily filly every last soul-affirming page of this most wondrous of novels.

The glorious good thing about Still Life, among the many gloriously good things that span its life enlivening length – which even at 436 pages is far too short; I could’ve stayed with Ulysses and his inclusive found family of lovable oddbods and misfits for hundreds of pages more – is the way it celebrates and embraces all kinds of strange and unusual people.

Nowhere in its length is this loving inclusiveness begrudging or halfhearted.

In fact, it is unstinting in its generosity, expansive in its depth and breadth and wholly non-judgemental in every way, shape or form; this is love as it is meant to be lived, unconditionally, fulsomely and rich alive and willing to take anything under its wing because it accepts in their entirety the person doing the things.

As we come to know Ulysses and Evelyn, Peg, Cress, Alys, Michele and Giulia, Des and Poppy, Pete, Col, Ginny, Mrs Kaur and a host of others, all of whom you will come to love and adore unquestioningly and without reserve, just as the characters accept and love each other without even placing limits on it, and the city of Florence which is its own, forthright, personality and culture-filled character, we see love painted in ways we might never considered.

Or perhaps we have, but here in Still Life we see it presented as it really is, set free from prejudice and grotty judgement, bigotry and condition, accepting the queerness and strangeness of life in its totality and create a self-sustaining world that is far from insular but which interacts with the world as it is while also crafting an oasis of its own that acknowledges the casual, cruel realness of life without being dominated or subsumed by it.

“When she got to the door, she said, What did you say?

I said you could never disappoint me, Alys. I’m proud of every inch of you. Every minscule part of your being. Of your thoughts and your joy and your rage. The way you sing and navigate you sing and navigate your way in his often godforsaken—

I love a girl.

(PAUSE.)

Lucky girl, I say— world.

They looked at one another and the distance halved. Ulysses said, A new year, Alys. I hope it’s worthy of you.

Night, Uly.

Night, kid.” (P. 243)

Still Life is profoundly, heartstoppingly moving, a warm neverending hug of a novel that knows the might and power that goes into embracing another person and accepting them wholly and completely as they are.

Writing with wit, wisdom, insight and an affecting understanding of the human condition in all its boundless difference and mainstream nonconformity, Still Life is one of those rare novels that knows the world is unremittingly difficult and harsh but which counters that love, real muscular, warts-and-all love, is more than up to the job of dealing with it.

More than simply dealing with it, love is able to stare life in the eye, daring it to challenge what it has created and demanding that it yield to the close bonds of family and belonging, selfless love and care and a boundless generosity of spirit that than can handle pretty much anything.

There is so much rich loveliness and human beauty in Still Life, a delightfully enriching story that is told with luxuriously good language, cleverly, humourously and affectingly used, a deep appreciation for the majesty of well-wrought characterisation, and a real sense of how bad life can be and how broken people are, and yet how much love can counter that in ways that are far from lightweight and fleeting but which can change and influence people over decades, all of them the better for having given themselves over to its unconditional and all-encompassing power and life-altering influence.