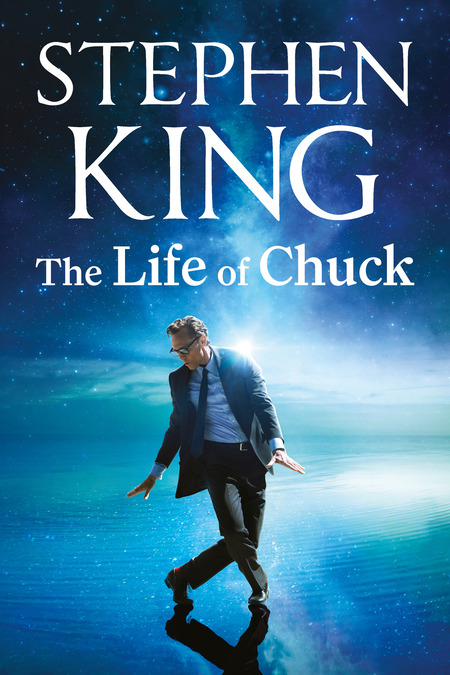

(courtesy Hachette Australia)

Like many other people, I am well acquainted with Walt Hitman’s immortal line “I contain multitudes”, taken from his poem “Song of Myself, 51”.

It is one of those popularly understood but not always fully ruminated on lines that resonate with people, even if many of us haven’t really taken the time to consider why.

At its core, Whitman’s beautiful introspective musing refers to the fact that all of us contain a great diversity of beliefs, life experiences and ideas, not all of which slot neatly together; we like to think of ourselves as one easily-defined person composed of an easily discernible set of thoughts and beliefs, but we aren’t and any attempt by someone to pigeonhole us as such is going to come to nought.

It’s this central wondrous idea that forms the heart of Stephen King’s now-novella The Life of Chuck – it was originally released as part of a novella collection, If It Bleeds, released in 2020; it has now been released a movie tie-in standalone novella – which comes subtitled as “Every life is a universe all its own”.

Told in reverse chronological order, The Life of Chuck brims with a hopefulness that stands in stark contrast to some of the events of the eponymous protagonist’s life, with each of the three acts in the story, beginning with Chuck’s death then his middle-age years then his youth, showcasing the central idea that articulated in the novella that “I am wonderful, I deserve to be wonderful, and I contain multitudes.”

‘The world is going down the drain, and all we can say is ‘that sucks’. So maybe we’re going down the drain, too.’

‘Maybe we are,’ he said, but Chuck Krantz is retiring, so I guess there’s a gleam of light in the darkness.’

What strikes you most profoundly, quite apart from The Curious Life of Benjamin Button/Pulp Fiction feel and flavour to the narrative, is now beautifully King expresses the idea of a multipilicity of selves contained within frail and mortal body.

Beginning with Chuck’s death, which happens in the most surreal of the three acts where his passing also appears ———- SPOILER ALERT !!!!! ———- to take down the entire universe, quite literally, with it, The Life of Chuck never strays from its mission to show how we are made up, over a lifetime of unconscious accretion, of a multitude of selves, not all of whom fit seamlessly with the other.

I mean, how can they?

Anyone with half a gram of self awareness or even a zest for life changes and grows and becomes someone else entirely and while the bedrock of who you are as a person may not change such as whether you’re an introvert or extrovert, adventurous or cautious, how that is expressed and lived is in a constant state of flux.

That’s by and large a good thing because standing still leads to the kind of fossilisation through which very small and woefully unfulfilling lives are lived.

The wonderful thing about The Life of Chuck is that King shows him trying to be someone who takes chances, who dances to a busker just because whimsy takes him, who dances with a girl at a school dance because why not be brave, and who doesn’t become an accountant even though his far more conservative grandfather Albie urges him too.

Now just because there’s all this rich, salient meaning, doesn’t mean The Life of Chuck isn’t a little trippy and odd at times; it wouldn’t be a story from one of the most interesting and imaginative writers of our time if it wasn’t.

There are times, especially in the first act, where you trying desperately to keep up with what appears to be the end of the world, all of it marching in fatalistic, end-of-times lockstep with the death of a man from cancer, who is seemingly everywhere in the world that the central character of this section, middle school teacher, Marty Anderson, inhabits.

It seems that as Chuck dies so does the world, an almost literal outworking of the idea that we contain multitudes and as we die, so does the universe we have unwittingly constructed within ourselves, one full of memories and stories and lives, all of whom cannot survive beyond our passing.

That’s hugely, if strangely poignant in the novella, which moves on from a unsettlingly surreal first act to a second one where Chuck, in another city for a work conference where he looks like a fairly ordinary suited guy, decides to dance to a busker’s beat with a young woman who is dealing with great pain.

It’s a delightful second act, which takes place just nine months before the death documented in the first act, and speaks to how those small moments of abandonment to joy and to impromptu surrenders to momentary escape from the everyday, can have so much meaning beyond the obvious.

He wasn’t, Chuck thought. I will insist that he wasn’t, and I will live my life until my life runs out. I am wonderful, I deserve to be wonderful, and I contain multitudes.

He closed the door and snapped the lock shut.

There is a mystical magicality to the final act where a high school-aged Chuck is given a prophetic glimpse into his own mortality – it’s not clear he connects the dots because his vision is done and dusted before he really knows what’s hit him – at the same time as he is figuring out who he is and who he wants to be.

It’s classic coming of age territory with some magical realism thrown in, and it beautifully shows how we are constantly making choices about who we are, how we will react to life events and what we will do with insights that we gain along the way.

Having seen where Chuck’s goes from the point on, the third and second acts come alive in even more vivacious, affecting detail, giving us insight into why he dances with strangers and how that is possibly the last pure moment of untrammeled joy before his life comes to a far too premature finish.

As a meditation on Whitman’s moving poetic epiphany, The Life of Chuck is a beautiful and moving piece of work that accomplishes more in 90-plus pages than many other novels accomplish in 400, and which leaves you shaken, in the bets possible way to a deeply affected core, all too cognisant suddenly that while others may see us as a singular individual, that we contain multitudes indeed and that together, contrary though they are, they make us who we are and gift us a life that though we know its ending, has so many places to go and things to express, and is wondrous indeed no matter what it contains.