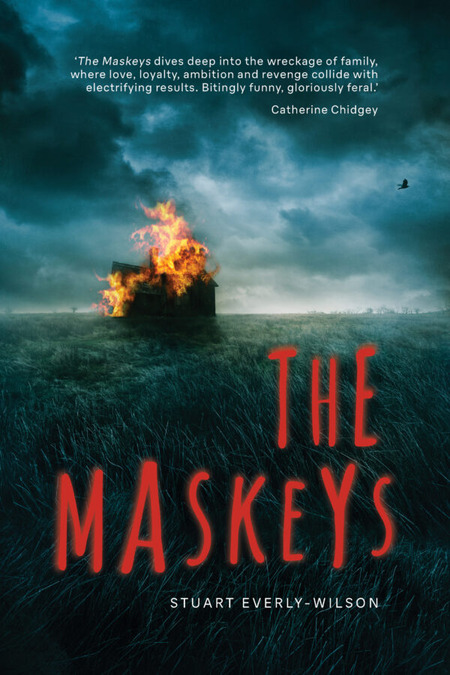

(courtesy Transit Lounge Publishing)

Despite this book’s title, The Maskeys, and no, this does not require a spoiler alert, are not the centrepiece of the novel which bears their rather blighted name.

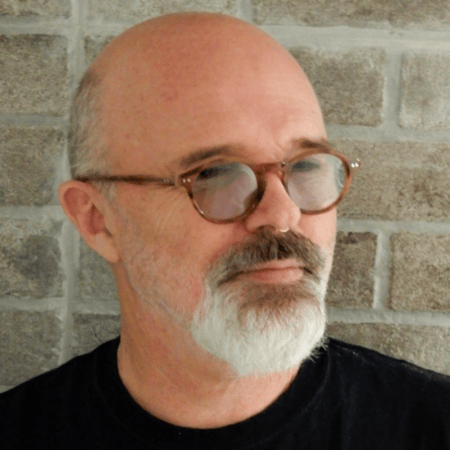

Penned by Stuart Everly-Wilson, who brought us the superlatively good Low Expectations, The Maskeys revolves instead around Rodney, a young, book-loving (rom-coms especially) unattractive man who has long existed, and sought meaning and purpose, in the orbit of a family which has been imploding for years by the time we join their eponymous story.

The destructive implosion of a family who casts a long and unwelcomingly fearful shadow across the fictional town of Naples in the Far North Coast of NSW has gathered a great deal of speed in the last year following some deep trauma which has seen the already teetering marriage of George and Hilda finally start to topple.

George was once the kingpin of the town’s drug trade, the lord of an army of dealers, who collectively destroyed themselves and others in pursuit of the big bucks to be made in a highly illegal trade, but while George still has a hand in the black market trade in illicit pleasure, it’s relatively low-key and conducted in part by his avaricious daughter-in-law, Celeste, an archetypal golddigger who is nakedly, messily clumsy about her goal of becoming a permanent part of the family.

The man behind what’s left of George’s much-detested drug trade – by the townspeople, although you could argue he’s increasingly sick of it too – is Rodney whose business guile and quick thinking has kept the family business, and arguably, the Maskeys themselves, ticking over long past their use-by date.

Feeling uneasy, he [George] turned from the ugly blaze and went indoors. He grabbed a beer from the fridge and sat alone with his thoughts at the kitchen table.

You may have worked out already that the Maskeys are not the most popular nor lovely of people.

Rounded out by 19-year-old son Caleb, who has made the poorly-judged decision to shack up with the highly dislikable Celeste, who has given George and Hilda a grandson who is hardly the apple of their eye, and gay son Billy who has only returned to Naples because his first adult relationship didn’t work quite as planned, the Maskeys are the sort of people, by and large, that you would not want to know (although, to be fair, they really don’t want to know each other either).

In less assured hands, The Maskeys would simply be the tale of a highly awful family best left to rot on the margins of society they know occupy – while people still fear and avoid them, they are less of a threat than they were, their ability to wreak havoc and revenge less actual than lingering – but Everly-Wilson does a masterfully engrossing job of giving these terrible human beings a three-dimensional edge that they might at first seem to lack.

That doesn’t make them likeable, at least not wholly, and likely not even a little in some cases – sorry Celeste but while we know what powers your gold-digging, you are still a poisonous slice of degraded humanity – but what it does do is make The Maskeys a fascinatingly compelling story of what happens to people when all they want is love and acceptance but don’t have the tools, even a little bit, to realise that in a healthy fashion.

(courtesy Transit Lounge Publishing)

Thanks to Everly-Wilson’s ability to add nuance and humanity to those seemingly and vacuously lacking it, we come to understand that even the darkest of souls have some vulnerability and pain to them.

This helps explain why they do what they do, but as The Maskeys artfully explains in a storyline which sees the town’s petrol proprietor Gayle kidnap Rodney and steal a crop of marijuana in a bid to enact revenge on George, thus setting in train combustible events which go to places she doesn’t expect, it simply explains the source of their miserable existences without once justifying them.

And therein lies the brilliance of this novel.

While Rodney emerges as someone completely at odds with your view of him at the beginning, as the young tragic offspring of a junkie finds someone he can love with all his heart, and not just the piece that can engineer his survival in a world that doesn’t seem to love him all that much, the Maskeys themselves, while empathetically well-rounded, fulfill every last idea you might have had about them.

But not in the nakedly obvious, cardboard cutout way that lesser writers might enact in their pursuit of some postmodern goal of humanising even the darkest and most degraded of souls in a bid to say “evil is just a darker shade of the original pure white of vulnerable, lost and emotionally rich humanity”.

‘As if he’d tell you [Rodney]!’ Gayle sneered. ‘You’re nothing to that man. You allow yourself to be used by him, like he used my stupid son,’ she said, snatching the letter back. ‘Don’t forget I’ve known that creep most of my life.’ She folded the letter away.

Where Everly-Wilson’s considerable skill lies is in not making the Maskeys objects of understanding and empathy, although some of that creeps in and helps us to understand why such a corrosive family has somehow lasted as long as it has, but rather helping us to understand what happens to people when they are pushed to the margins and they push right back, not always in ways legal or beneficial to themselves or the world around them.

The Maskeys is in many ways a love song to the “overlooked”, as the back cover blurb rather beautifully describes them, but it is not a love song of endless devotion or great care, save for Rodney who emerges as a moral compass of sorts and the most decent person among all the characters in the book (save for the town seer, trans woman Serenade, who knows a great deal and acts on it to impressive effect).

Rather, it lets its characters by and large hang themselves on their own foibles and failings, but situates them so that we understand that they act not out of evil, which is the obvious binary way to go, but out of a broken sense of what constitutes a good life and a desperate need to claw back what has, in some ways at least by a world not weighted in their favour, been taken from them.

Written with a penetrating gaze and a sharp gift for observation coupled with a rich understanding of what it means to be human, The Maskeys is deeply compassionate, not condoning the actions of many its characters but understanding why they do what they do, and in so doing telling a story that resonates with a palpable sense of humanity while communicating how easy it is to lose your way in the mud even if you are trying to navigate by and aim for the stars.