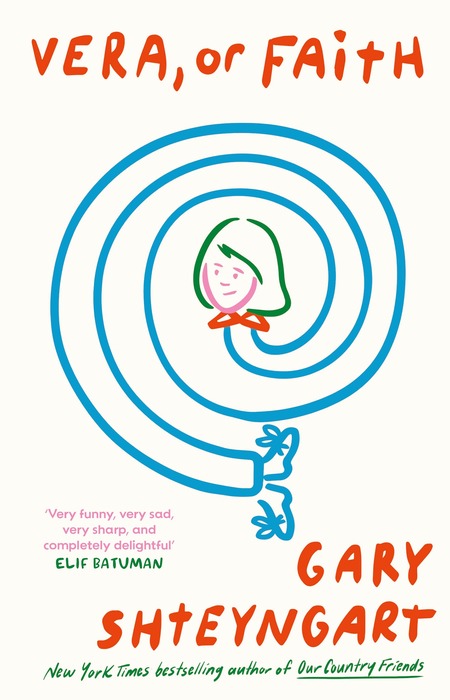

(courtesy Allen & Unwin Book Publishers)

Coming to grips with who you are isn’t easy.

It’s even less easy when you’re a ten-year-old girl who’s been raised almost in a vacuum of information about yourself and who can tell that the world she inhabits is not only built on convenient hiding of the truth but on a rickety familial structure that looks destined for imminent and possible final collapse.

The girl in question is the titular protagonist of Vera, or Faith by Gary Shteyngart, and while she is prodigiously smart, a student who clamours to be recognised for her impressive bank of knowledge by her teachers (“Being smart is one of the few things I have to be proud of”), she is also keenly aware that there’s a great deal of which she is not adept at in a near-future America where society which is in enthral to quietly corrupting forms of fascism.

In this world where self-driving cars can rat you out to the government and women’s menstrual cycles are monitored, Vera is trying to figure out what it means to be her in a world of which she only really has a limited understanding.

Her attempts to get to grips with who she is in a world that mystifies her are hampered by a fractious family set up where her intellectual Russian-Jewish father is pouring his considerable savings into a political magazine with a niche audience at best, his obsession with his publishing undertakings so complete that he neglects Vera, and her half-brother Dylan, born of the union between Vera’s father and his second wife, Anne.

She felt Miss Campari’s bosom approach her from behind and sucked in her breath, preparing to be smart so she could “advance in the world”. Often when she felt like she couldn’t breathe, her hand found the center of the clip-on bow tie and she pulled on it as if it were the string of a wind-up toy.

Vera is convinced that Anne doesn’t like her, or at least isn’t as invested in her as she is in Dylan but as Vera, or Faith progresses, all told through the limited perspective of Vera who freely admits there are things she simply doesn’t understand, it becomes clear that this relationship isn’t what Vera think it is.

In fact, her relationship with her stepmother, which is far more complicated and yet wonderfully simple and straightforward too, is emblematic of so much of how Vera sees the world.

She is, after all, only ten so it makes sense she would get things wrong, or at the very least, perceive them in half-baked terms; what Vera, or Faith does so beautifully is expose this in ways that aren’t cruel but which understand that even the adults among us don’t always see the light and the shade or the nuance of a great many situations.

What is particularly fascinating about a largely friendless Vera is that, brilliant though she is, she doesn’t fully appreciate that her accommodations with whatever happens to her or around her may not necessarily be the best way to approach things.

For instance, she is placed on one side of a debate competition at school whose mission is to explore the pros and cons of a particularly odious piece of racist legislation that will grant certain “worthy” Americans (read: white) greater voting rights than their non-white counterparts.

(courtesy Penguin Random House © Brigitte Lacombe)

She intellectually knows that her liberal parents will be appalled she is being asked to argue in favour of the legislation but Vera is too excited by the educational opportunities, and the chance to be recognised for her brilliance, that the debate offers to really see beyond this limited perspective.

One thing she can see is that the debate offers her the chance to finally make a friend, Yumi, the daughter of Japanese diplomats, who embrace Vera and show a welcoming sense of family and friendship that she longed for for quite some time.

The preparation for the debate, while typically vigorous for a girl who knows anything else beyond excelling intellectually, becomes far more important to Vera as a way to spend time with Yumi, whose friendship feels like a strangely unexplored country that Vera has to navigate like she is the first one on its shores.

And for Vera, that’s exactly how it feels.

Adrift in ways she can’t articulate, Vera clings to Yumi’s friendship, though she’s bright enough not to look to clingy or needy, as the emotional plug for a hole in the soul that education can fill to some extent but which needs one big mystery to be solved for Vera to feel totally at ease – exactly who is her real mother?

The thing is, of course, that when that massive question does get answered at the end of Vera, or Faith, it does do what Vera thinks it will and she, in fact, finds surprising love and acceptance from a wholly unexpected quarter.

For the first time in her life, Vera had stopped reading in the middle of something. She could read no longer. She could read no longer about herself in the third person. She did not want to exist as words on a document, words in a letter. She did not understand all of what she had read, but somehow she had to.

But that is the end of things, and much of Vera, or Faith exists in the here and now where America is tilting ever further to authoritarianism, Vera’s family is slowly crumbling around her as Igor lives in his own hermetically-sealed world and Anne tries to keep the family running anyway, and one young girl is trying to figure out who she is, why she is and where she is.

It’s a lot to ask of anyone and Vera at least understands that to some extent but like a palaeontologist making educated guesses about how a dinosaur might have looked based on an incomplete skeleton, Vera does her best to work out what’s happening in her life on a number of levels by observing and trying to interpret what’s going on around her.

She’s aided in this most adroitly as it turns out by her AI chess partner Kaspie whose ability to make sense of things beats Igor and Anne hands down, even though, being an artificial entity at the end of the day, its perspectives are only as good as its algorithms and its limited self-learning opportunities.

While Gary Shteyngart casts his narrative net far and wide, examining America’s descent into quietly barbarous fascism and how family is often a rocky shoal rather than a safe and welcoming harbour, Vera, or Faith is a beautifully compact novel about one girl trying to figure out her sense of self, her family and her possible friend as she tries to work out where all that fits into a wider world which, despite her best efforts, defeats her valiant, if limited, attempts to understand it.