While COVID hasn’t gone away, and is currently once again doing its best to derail Christmas, 2022 did return sufficiently to something approaching normal to allow a lot of cinema visits over the last 12 months.

Suddenly catching up with friends over dinner and a movie became an almost weekly thing again, mask on even when they were no longer officially mandated, and while there were still lots of streaming possibilities, which I made the most of, there was something wonderful about once escaping into a darkened room for a couple of hours and keeping the rule very much at bay.

Once again, I watched an eclectic bunch of movies, reflecting the fact that my interests run wide and deep, with a week possibly including an animated feature and an indie drama or a sci-fi adventure or a coming-of-age thoughtful story.

What I love is diversity in storytelling and cinema gave me that again this year, making my work-a-day world feel a whole more alive and vibrant and enthralling my spirit with a host of stories like the 25 I’ve selected as my best of the year …

Musically exuberant and emotionally raw and dynamically optimistic, the film signals a rebirth for just about everyone involved, literally singing the power of connection and belonging as a found family of rock chicks and conservative neighbours, mail carriers and record store owners looking for a way forward come together in a way that warms the heart without once feeling twee or uselessly sentimental.

While the third act is a little too rushed and predictable in certain respects, Mixtape is for the most part a delightful joy, the kind of film that should be watched by anyone mired in the past who wonders if the future holds much promise at all, and who’s ready for a journey of discovery, the kind that might take them to places unexpected and painful but also wonderfully rich and possible, the ones that can ultimately redefine who we are are, and as Beverly hopes, who we might come to be.

Herbert’s story is rightly seen as an intricately intense and huge tale of humanity at war with itself, with themes of genocide, colonisation, exploitation and war all prominent and engagingly and thoughtfully delivered, but it is also the small “h” humanity of one person who finds himself, far from being an unsure bystander to the great sweep of history as a whole, and that of House Atreides and Arrakis in particular, at the very centre of everything.

The director keeps these big and small aspects of the film perfectly in compelling tension, giving the vastness of landscape and action room to express themselves while allowing characters such as Paul, his father and mother, Duncan, and even characters like Dr. Leit-Keynes (Sharon Duncan-Brewster), the Imperial ecologist charged with overseeing the transition from Atreides to Harkonnen on Arrakis, to fully come alive and radiate their humanity into a story which is all the better for their groundedness and emotional openness.

Dune is a landmark piece of cinematic sci-fi storytelling which is enthrallingly immersive, brilliantly epic, rich in character and emotionally evocative while delivering up political intrigue and action – a perfect sci-fi space opera writ brilliantly large as these types of movies always should be and which stands the film in good stead for the thrilling conclusion of the tale to come.

As a brilliantly exuberant adventure to save the future, The Adam Project is a joyous piece of fun, buoyed considerably the witty repartee between ATY and ATO, who believably represent the idea that they are one and the same person, just separated by almost three decades.

The quips, oneliners and witty putdowns fly fast and free, some of them juvenile (they’re kind of weird time travel siblings after all) and some of them poignantly incisive, and they are a blast to watch with the chemistry between the two actors a real delight, but they really come alive because the film never once forgets the pain and loss elephant sitting clearly in sight in the figurative room.

The Adams are hurting, and while ATO is there to rescue someone and fix things good and proper as every hero from a bright, shiny (or not) time travelling future is wont to do, The Adam Project is kind of, in the best tradition of all family-friendly blockbusters, there to put a hand on your heart, squeeze heartily and get you laying on a couch blabbing out all your great regrets and grief about life in one taut, tight, thrilling package.

Sure there’s a big massive time paradox to fix, and awe-inspiring tech with which to fix it, and it’s big, bold and utterly brilliant, but at its heart, one fashioned with some real originality and a distinct sense of fun, its about how one broken boy meets his still-broken, and a little bit twisted by time older self, and fixes what ails him in ways that will go a long way to mending your own broken heart in ways you didn’t know you needed.

For all its willingness to be unstinting about life’s potential for darkness and loss, reflected in some desperately lonely passages when Tom looks so bereft and alone that you want to hug him tight and drive him to Land’s End yourself, The Last Bus is also a reassuring delight with Tom temporarily becoming part of the lives of people like Peter and Tracy (Steven Duffy and Patricia Panther respectively) or Ukrainian woman Maria (Susannah Laing) who’s birthday party Tom becomes a part of after one of the bleakest days of his trip.

One of the loveliest scenes in the film begins as one of its most uncertain, with Tom surrounded by drunk male football fans and hen’s party girls, all of whom are quieted to an unusual late night bus stop reverence when Tom, encouraged by a mournful drunk man almost his age, sings “Amazing Grace” and literally stops everyone in their tracks.

It is emblematic of a film that isn’t given to overblown statement or emotionally manipulative impulses, preferring instead, quietly and with a poetic nuance that embraces life as it is, good and bad alike, to let Tom be the centre of attention, an assuming man of singular focus whose only focus is the one he has had all his life which is to do the right thing by his beautiful wife.

The Last Bus is almost mournfully ruminative at times, but it always present Tom as a full-realised man of decency, respect for others and uncommon bravery who even at the darkest, near-final point of his life is committed to doing the right thing by others who in return do the right thing by him (mostly but not always) and whose singular devotion to the love of his life rings true with a moving truthfulness that seizes your heart at the outset and never really lets it go.

Everything Everywhere All At Once

The ending of Everything Everywhere All At Once is unashamedly warm and fuzzy and emotionally inclusive that reaffirms how reconnecting with those you are actively or often just unwittingly estranged from can remake your life in remarkably powerful ways, but right to the end it manages to balance the mad with the meaningful, the crazy with the caring and the silly with the very, very serious.

Like a magical trip to all the place your life could take you bundled in with an examination of all the reasons why it didn’t, Everything Everywhere All At Once is a rare and madcap gem of a film that manages to dazzle you with an inventiveness of worldbuilding that astounds and overwhelms in the most marvellous of ways while putting humanity and heart front and centre, creating in the process one of the most original and thought-provokingly movies you are likely to see in this or any other year (providing of course that your alternate self hasn’t got access to an even better slate of films which seems doubtful when movies are as gloriously good as this).

At its very beating, affecting and thoughtfully meaningful core, Belfast is one of those films which manages to combine the grand sweep of history with the intimacy of close family life, and do so in such a way that it’s impossible not to wonder what we would do if our world was shaking to the core and we had the unenviable choice of staying or going?

What would we do? Belfast agonises over this in ways witty and charming, and confrontingly sad, with its final act providing a powerful answer, one which will tug profoundly at your heartstrings, engage your mind and make you consider how you are defined by where you are, and where you were, and how the loss of that might define you in substantial ways that will resonate through the rest of your life.

Doctor Strange and the Multiverse of Madness

Realities, by the way, that, thanks to director Sam Raimi, and masterful screenwriter Michael Waldron, are scored heavily with distinctly unsettling but thrilling horror elements which work brilliantly in a story where up is down, hope is despair and death is not always the end of things.

These dark, often occultic elements find a natural home in Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness which even in the 2016 predecessor hinted that the world, or worlds, that Strange inhabit have the potential to become scarily different to the flesh and blood reality we all know and occasionally love.

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness runs with these elements and host of other gobsmackingly immersive narrative ticks and blindingly good leaps of imagination, all of which land exactly as intended, yielding a film that makes the absolute most of its premise, while keeping some very broken humanity at its beating core, giving us not simply one of the most brazenly good and emotionally impactful films of the year but of the entire Marvel canon, confirming the current phase of films as likely the best of an already impressive bunch of superheroic movies.

While Johnny initially rejects Jesse’s decidedly odd way of dealing with the trauma of his broken, though loving family, he soon realises this is his nephew’s way of dealing with it, and without any clear plan of what to do (he relies, on Viv’s advice on parenting prompts via Google, which leads to one gorgeously meaningful scene with a clearly amused Jesse), he slowly builds a relationship with his nephew that leads, in some, tense, funny and realistically touching ways, to them both finding some accommodation with a seriously f**ked up present.

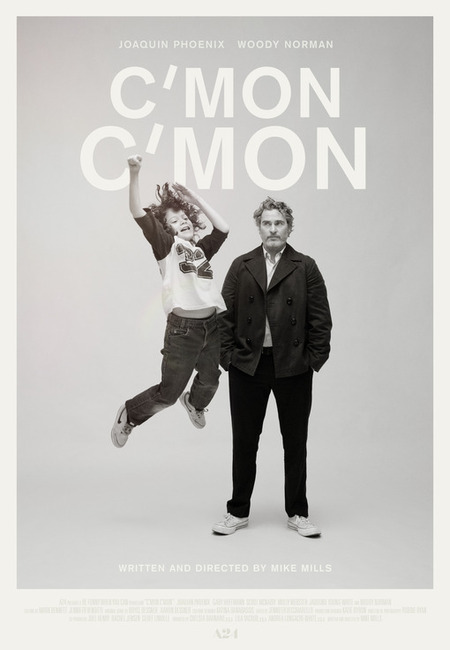

Every step of its narratively and visually, character-rich way, C’mon, C’mon is a quietly immersive joy, a film which might look wholly separate from the cinematic pack but which feels warm, alive and quietly in touch with what it means to be human, all too aware that for all the good things life can offer like family and belonging, there’s a host of dark and terrible things too, none of which it groundedly maintains should be fatal if you’re open to be real, honest and importantly, willing to put in the time to see where, together with those you love, life may take you.

By the end of After Yang, Jake, Kyra and even Mika, who draws closer to her father especially during the emotionally turbulent rush to save Yang – again “rush” may be the wrong word though there is brittle, desperate urgency in every languid scene and hesitantly troubled moment – there is a sense of moving on but only in the way that that is forced on the family.

They would far prefer Yang to still be there, as would anyone who grieves the passing of a loved one, and their journey to finally accepting his absence is an agonising one that Kogonada captures with insightful humanity and deep understanding that will catch your breath at times, but move on they must finally do in a reflection of the way life keeps dragging us ever on, even if we wish we could stay bubbled away in those small precious moments of memory that sustain us in the wake of the capacity to make new ones being ripped from our grasp.

As poetic meditations on death, love, grief, humanity and loss go, After Yang is a brilliantly affecting piece of work, a journey into the darker places of the soul but also to renewed love and connection, the kind that often find themselves when a chasm appears in our lives, which looks beautiful and stunningly gorgeous, all while embracing an emotional honesty that captivates and immerses, and which, containing compelling performances from all concerned, enthralls you from start to finish as you watch Jake, Kyra and dear little Mika come to terms with what the rest of their life might look like when what it was ends with no fanfare or warning and they are forced to embark on the hardest journey anyone is ever called to make.

It’s a film that has plenty of slapstick and verbally comic athleticism, but also the tremendous existential pain of Buzz having to watch all his contemporaries, now 62 years older than he is, live rich and full lives while he is barely hours older, and MacLane, who co-wrote the immensely affecting screenplay with Jason Headley, also keeps this very much in mind throughout the film which had to wrestle with the central idea of whether Buzz not getting people home almost a century older is a failure that should be righted or a reality he simply needs to accept.

You can almost watch the tussle on beautifully animated Buzz’s face – his hair in the wind is a thing of animated beauty that is worth the price of admission; kidding but damn it’s hypnotically gripping (in fact all the animation is photo-realistically rich and immersively wonderful) – as he has to make some huge existential decisions that will have a direct impact on his new friends.

It’s an intensely affecting emotional arc that is not lessened one bit by the appealing flippancy that surrounds it, testament once again that the superlative skill and maturity that Pixar brings to their animation which, like life itself, is a mix of the good and the bad, the obvious and the fiendishly, heartrendingly challenging.

Lightyear is a superbly good origin tale, not simply we can see why Buzz the toy was initially how he is, but because it’s swashbuckling, ’50s movie serial sense of fun and high stakes, beautifully captures what it means to belong and to lose that sense of connection, to fight for one ideal only to find the truth is another has taken its place thanks to the passage of time, and to fight for what matters when, of course, you finally, and affectingly figure out what that is.

Watching Cha Cha Real Smooth you get a beautiful sense of what it means to find a kindred soul in your corner when it seems no one really gets what’s happening to you.

Sure, Andrew has his supportive mum and is heartwarmingly close to his younger brother, but even so he is alone in his lostness so when he meets Domino who gets what’s going on for him because she’s about to leave that place even if she is a little hesitant to do so, it makes sense they draw closer and closer until …?

Honestly that is one or two spoilers too far, so we won’t go there, but suffice to say that Cha Cha Real Smooth does an exemplarily moving and sweetly funny job of defying expectations, going real and deep about what it means to be human when everything’s unnervingly indistinct, and painting a beautiful picture of connection and belonging and holding your nerve wherever you are in life because, anxiety aside, and yes it can be corrosively unsettling at the time, you will find your way out and when you do, well, it will likely be nothing like you imagined and precisely what you need at the time.

Predictable though much of the film is, it feels fresh, real and original, a fairytale of newness and reinvention that might be packed full of happy coincidence and neatly-arranged outcomes, but which feels like something heart-affirmingly alive and real.

Tuesday Club (Tisdagsklubben) is a delight to watch, to lose yourself because all of the characters, bar petulant Frederika at times and Henrik in his first few prickly, primadonna scenes, are a joy to spend time with – Pia and Monika are the perfect, supportive and reasonably well fleshed-out besties, the cooking gang including sweet novice cook, plumber Grizzly (Klas Wiljergård) are exactly who you’d want to help distract from the ashen mess of your life, and Henrik, once the screenplay allows him to warm up and soften, and become appealingly vulnerable, is the epitome of the new man poised to remake, reinvent and restore Karin’s life.

On paper, Tuesday Club (Tisdagsklubben) isn’t wildly original but what it lacks in innovation and difference – to be fair a good, no great rom-com, should be a slave of sorts to its genre or its missing the point of its existence – it more than makes up with a vitality of found community, a comedic sensibility that is as heartfelt as it is hilarious, and characters so richly alive and approachable that you want them all to be happy because if they can be happy after the worst happens to them, so can you, and in a world that often feels cruelly cold and unforgiving, that something of which it’s always good to be reminded.

Prey is lavishly textured and narratively complex, a film that feels as much like an indie exploration of culture, the passing of an era and and person’s reckoning with who they want to be, as it is a race against a bloodthirsty enemy whose only concern is besting every opponent that comes its way, and the one person who turns out to be capable of standing in its way, shattering expectations everywhere as she does so.

Near flawless in its execution, Prey is the best thing to happen to the Predator franchise in years, turning the hunter into the hunted, placing primacy on Comanche culture in a way that is vibrantly authentic and meaningful and delivering up a protagonist who is bold, likable and every bit the match for an alien hunter who discovers that perhaps they are not the top of the heap after all, a realisation which fits neatly with a film dedicated to shattering expectations every step of its mesmerisingly immersive way.

The reason why Good Luck to You, Leo Grande is so adept at ripping your heart, exposing it to the startling light of emotional day before healing it and placing it back from whence it came is because the film is so raw and so honest, especially about the grinding disappointments Stokes feels about her life and her fervently nervous need for Grande to help her leave them behind, that it ends up speaking volubly to every single one of us who have wanted more from this thing called life.

This universality, of course, is a byproduct of a film that is first and foremost devoting itself to the way in which many women are forced to shelve their hopes, wants and needs in favour of the welfare of others, all underscored by incessant calls from Stokes’ daughter throughout the film, all of which she habitually answers during her sessions with Grande because, as she tells him, that’s what mothers do, and how even when they do take a step towards their own empowerment they can be undone by the lingering voices of others seeding their self-doubt and reticence to push beyond the boundaries of their sclerotic lives.

It’s a tragedy, and at times feels like an insurmountable one during much of Good Luck to You, Leo Grande, even as Stokes takes tremulously transformative steps forward, but the film is at pains to speak to the power of tenacity and hope and to the fact that the moribund of lives can find vibrant new expression past what those living them might fear is their expiry date.

Richly, relatably funny and universally movingly true to the point that you can’t walk out of the cinema unaffected, Good Luck to You, Leo Grande is a gem of a film powered by performances so intensely raw and comedically honest that you feel every last drop of disappointment, every sliver of hope and every tentative step forward, all of them so specific and yet so universal, that you can’t help but feel as if your soul has been ripped open and remade in ways that feel every bit as profound as the characters on the screen themselves.

While the burn is slow when it comes to OJ and Em and Ricky’s relationship with what is or isn’t out there, their reactions speak to the way in which people don’t always pick the right option when it comes to fight or flight, with our addiction to the intrigue and spectacle of something often cancelling out self-preservational caution.

While OJ and Em do end up taking the fight to Jean Jacket in ways that are harrowing, emotionally charged and simply spectacular in their execution – the cinematography is jaw-droppingly intense and makes looking away, even you’re creeped out, all but impossible – their fascination, and that of Angel and Ricky’s, with what it is and what it can do, goes beyond what’s healthy much of the time.

You can understand why that is since emotional trauma of two distinct kinds is informing OJ, Em and Ricky’s responses, and in the end how they respond, does make sense, but in amongst some very good decisions, there’s an unhealthy obsession with working out what’s going on that perhaps should’ve been set aside in favour of some good old flight time.

Still, Nope is at heart, a deep dive into what makes us human, and how past events can predispose us to reactions that may not be in our best interest; with a heady mix of gigantic spectacle, dark humour (the signature use of the word “nope” by OJ is pitch perfect) and some truly terrifying moments preceded by a lingering sense of dread and extreme disquiet, the film, while not perfect, is a thrilling descent into fear and terror and an energising ascent into what happens when fight wins out over flight and we take the battle to what truly terrifies us.

Based on Foster, a 2010 novella in English by Claire Keegan, The Quiet Girl is an immersively arresting story that never strays from the fact that life is hard and pain is inevitable but for all its cognisance of the brutal darkness of the business of living, knows that moments of light, hope, promise and love are possible and that they can salve the soul, however imperfectly, in effect or duration.

It is hard not to feel deeply for Cáit, Eibhlín or Seán, all lost at first in broken vulnerability, each of them searching for a new beginning, or if that can’t be sustained, simply some flicker of hope that life can be good again, or one lonely, sadly withdrawn little girl, can be good at all.

As films that dive deep into your heart and rip it out and then place it carefully and restoratively back in again, The Quiet Girl is a gem, a film that understands both the darkness and light of life and love, and how that is expressed for better or worse.

The Quiet Girl is filled with so much emotion —- SO MUCH —- all carefully and thoughtfully sowen into a film that’s as quiet as it’s protagonist but like her, filled with multitudes of longing, need and love, not all of which gets answered quite in the way anyone wants but which shows that that kind of love is possible and might be found again although we may never be party to it.

We’ve all got regrets about things that we can seemingly do little to nothing about, and while I Used to be Famous does give Vince some freedom from this, it doesn’t pretend for a second that life is so easily fixed that you can meet a neurodiverse kid, find your creativity and sense of life purpose renewed and skip off happily into the sunset.

I Used to be Famous is thankfully not that simplistic, choosing to focus on the fact that while happy endings of a sort are possible, they are not, by any means, going to fix things wholesale and not without some scarring still being evident.

It’s this commitment to raw, real humanity in the midst of a redemptive tale, coupled with knock it out of the park performances by real-life neurodiverse actor Long, Skrein whose face is a tapestry of pain, hope and bewilderment, and Matsuura who embodies every woman who has put aside her own dreams to care for her kid, that give such emotional muscularity to I Used to be Famous.

Sure, it’s full of skillfully and movingly well-used tropes and clichés, but they are not the sum total of the film, nor the whole reason for its existence, with I Used to be Famous having a huge amount of truly worthwhile things to say about the rich value of human diversity, of the way the past and present interact and how it can challenging but not impossible to deal with them to find your way to a fulfilling future, and how found families, of the most unlikely kind, can transform lives in unexpected and wonderfully life-affirming ways, leaving life far better than it was before they came along.

There is considerable reason for Ali and Ava to doubt they will ever find anything approaching love again given how the course taken by their previous relationships, but little by little and meeting by meeting, all of them punctuated to one degree or another by music which is a powerful motif throughout (it underscores their differences but commonality too), that perhaps the mythical second chance is not so fabled after all.

There is quiet thoughtfulness to Ali & Ava that belies a powerfulness of emotion that is always present; it may not shout it from the rooftops nor make its presence known with marching bands and ticker tape, but it is there, it makes an impression that stirs up a joy and an affecting sense of belonging that comes through in ever increasing measure until a final scene that is so astoundingly and yet simply beautiful that you will marvel how so much quiet restraint can contain so much transformative emotion, the kind that feels like a tsunami of possibility but also of coming home.

Ali & Ava is a gem of a film – it is deceptively quiet and nuanced, hiding within the richness of its meditative progress a depth and power of emotion that will floor you and inspire you as the two leading characters who have been beaten down by life, but not completely, discover in each other a place to belong and someone to belong there with, proving that love can exist in even the most beleaguered of circumstances and lift you up in ways that reassure the heart that life is far from being done with you yet.

It’s a rare thing to find an aspirational film of dream fulfilment and hope realised that isn’t just welcomingly soul-stirring but also emotionally meaty and moving too but Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris is that movie, a gem of a tale that brings together sparklingly vibrant characters, a woman who might just find love but makes of her own life what she will first, a found family who rally around the idea that you rule destiny and not the other way around, and a reassuringly emphatic nod to the appealing notion that dreams are never too old to pursue and that you owe it to yourelf to do so because who knows where it will lead.

Well, if you believe Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris, and after the terrible time we have universally had of it over the last few years, you really should, it will be somewhere good, very good indeed, and you will be glad that you, like our titular character, dared to dream, act on it and not let anyone get in your sweetly determined way.

The great and gloriously affirming truth of Joyride is that we are always caught between painful truth and abstract expectation and they real freedom and emotional release comes when we cast all that aside and simply deal with our lives as they really are.

It takes bravery and real honesty to do it, which takes both characters a wild to find, but when they do, Joyride comes even more heart-affirmingly alive, reminding us that even in the very worst of times, and good lord Joy and Mully are definitely there with weighted bells on, beautiful things can happen and we can find our own paths to whatever awaits whenever and however that may be.

So, Enola, though grateful for her brother’s deductive reasoning and support, must make her own way in the world, reminding everyone with pizzazz and a readily funny turn of phrase that she more than has what it takes to be as good a detective, if not better, than her brother.

Watching her leap from clue to clue, gathering them up like collector cards before arranging them just so in such a way that the game, which is most assuredly afoot, is well and truly pumping with vigorous energy, is one of the supreme delights of Enola Holmes 2 which is a fizzy bottle of fun but with a ferociously intelligent mind to match.

It is also a rom-com of sorts as avowedly independent Enola, whose mother begins to wonder if she made her far too self-reliant for her own emotional good, comes to realise that handsome, dashing, social justice-oriented Lord Tewkesbury (Louis Partridge) might be the perfect addition to her solo world which may not need him to make her way in the world or solve crimes, but who she desperately wants and needs for a whole host of other reasons that she only begins to discover in the film are as necessary as jujitsu and a witty, ferocious intelligence.

In a world which still can’t see how good women are much of the time, and which constantly underutilises one of its greatest assets, Enola Holmes 2 is a fun-filled pushback against male mediocrity which manages to creatively and imaginatively reinvent a well-loved literary character’s world while making all kinds of important necessary points about the capability of the women, and one feisty, funny, incisive one in particular who you love all the more by story’s end, while making us feel like a million, phosphorous-untainted dollars and ready to do what needs to be done because really who is going to stop us?

For a film that largely rises and falls on the epically visual worlds that Trip and Nemo journey through in their journey of identity recapture and emotional healing respectively, Slumberland, which is not short on knockout ideas of how dreamland and the dreams that make it up should look, looks like it’s stuck in a perpetual buffering loop.

Much of the CGI pixelated and cheap, and while that might sound like the most superficial of First World criticisms, its lack of finish means that you are often taken fully out of what is a deeply harrowing emotional journey, especially for Nemo who NEEDS all this gallivanting to pay bigtime.

It doesn’t ruin the film of course which is profoundly affecting to its very core, but it mars it enough that you long for the perfect marriage of imaginative visuals and emotionally rich story which Slumberland could’ve have been with a bigger budget.

Overall, Slumberland is an emotionally evocative through the very worst of things that can happen to a person, and while resolution is forthcoming for both Nemo and Trip, who both find their way home, and come alive again, the film doesn’t make it easy for them, especially Nemo who must journey through some dark (if ironically super colourful dream landscapes), to come out the other side and to be reminded that life still has much in store for her in the Waking World.

Margrete notes early on to the sometimes reluctant rulers of the constituent kingdoms and their attendant nobles that peace requires work, such as the raising of a Union army, and that supporting it should be a no-brainer since the prosperity and lives saved should be all the argument you need.

Alas, that isn’t enough for some people, including some within the Union camp, who actively conspire in the wake of the appearance of Fake Olaf to destabilise the grand Nordic experiment with peace over war simply because it will deliver them short-term riches and power accumulation.

What appears to a self-evident benefit to many, including Margrete, turns out to be an impediment to immediate personal gain for others, and much of the entrancing viewability of Margrete: Queen of the North comes from the fact that it explores in ways deeply languid and yet furiously intense what happens when communal idealism meets narcissistic pragmatism.

It is engrossing to watch and it’s highly unlikely you will find yourself checking your watch at all, with Margrete: Queen of the North not simply a brilliantly executed history lesson but also a sage examination of how humanity can dip towards its baser nature even when the benefits of peace are so clear, and how those of good heart and mind (and more than a little coldblooded tenacity and pragmatism) must stay true to the course if idealistic undertaking are ever to see the sustained light of day.

There is, as a result of all those characters musically and with dialogues that snaps and sizzles with improvisational vivacity – watching Ferrell and Reynolds go back and forth on Tiny Tim’s real name is hilarious and one of those scenes you want to rewatch as often as you can because its just so damn clever and funny – a lot going on in Spirited but it never feels overblown or overdone as it uses CGI magic well to take us across time and Manhattan in pursuit of souls changed for the unending duration.

The kick in the film is that maybe it’s not just Clint who needs to change but everyone and that maybe even the very best of things, and Marley’s supernatural change organisation, which breaks into riotously uplifting song far more than he cares for, needs a good lick and polish and wholesale retune lest it lose its way, not so much into irredeemability but simply ruts big enough to swallow a couple of centuries’ worth of hopes, dreams and unrequited love?

Spirited is a gem, a film that attempts a great deal and pulls off a great deal, replete with songs that surge with blistering life and existential conflicts, characters who actually move beyond one-note enablers of narrative redemption and a script that takes an age-old plot device and makes absolutely merry and bright with it to such an expansively huge extent that you are awed and delighted by it while being reassured, as you happily sing along, that maybe change is possible, that it can last and that maybe, life’s usual tropes aside, you can have the happy ending you’ve always dreamed of, or if you’re Clint and the Ghost of Christmas Present, the one you didn’t even realise you musically needed.

In many ways, Avatar: The Way of Water is a horror story, a tableau of terrors played out on a people and a place where harmony genuinely reigns, a connectivity of life that isn’t wafty or New Agey but rich, real and with considerable emotional heft.

This is life lived large, and Avatar: The Way of Water celebrates both its greatness and grandeur but also its emotional granularity in the form of the Sully family who exemplify what it means to belong to each other, to their clan and to the immeasurable complex and infinitely beautiful world around them.

Brought to the screen with a visual lushness that will take your breath away, Avatar: The Way of Water is a superlative example of what a blockbuster can and should be, leaving its big screen rivals in the dust, its visuals are awe-inspiringly lovely (so real you want to run through the forests and dive into the seas), its characters compelling, its story nuanced and thoughtfully immersive with long passages just devoted to being, not action, and its message a critically important one, woven into the greater whole with the same care and attention as every other flawlessly-rendered element, reflecting the same wholeness and aspirational beauty that typifies Pandora and which you can only hope we one day find here on Earth.