You write a best selling novel that sweeps the world. You are feted and adored as a creative wunderkind, speaking to your generation. The press adores you. Readers hang on your every word. Everyone is beating a path to your door.

Including Hollywood. They come a-calling, and buy the rights to your story for a squillion dollars. Surely the next step is to craft a screenplay befitting your literary masterpiece?

Possibly. Often they use their own screenwriter but what if they offer you some say in how your book translates to the silver screen? Do you take it?

Surely the question doesn’t need to be asked since everyone wants to make it big in Hollywood right? So wouldn’t a writer, especially one with a novel atop the New York Times bestseller lists, be exactly the same?

Not necessarily. And it’s got precious little to do with whether you want recognition for your artistic efforts. Of course, you do. You’re a storyteller at heart and you want to know that the stories you tell matter.

So how do you decide how involved you get with Tinseltown? There is, of course, no hard and fast rule but perhaps the following examples can help you work out what you would do should you ever write the novel to end all novels and Hollywood comes knocking at your door.

No screenplays please, I am an AUTHOR.

Taking this position doesn’t mean that you are a militant revolutionary, clinging nobly to the purity of creating art for art’s sake. Yes there are some literary snobs out there, but what it usually means is that you are happy to be an author of books, and only of books, and you are perfectly content to leave the screenwriting to the movie professionals.

If you are of the opinion that neither art form is superior to the other and are happy to let your book be interpreted as the screenwriter sees fit then you are in good company.

Kazuo Ishiguro, author of the book, now movie, Never Let Me Go was quoted as saying to the film’s screenwriter, Alex Garland:

“Your only duty is to write a really good screenplay with the same title as my book.”

For Kazuo, there was no conflict, no artistic angst to resolve. He writes books, Alex Garland writes screenplays and they would, by definition, create two different artistic statements. As it turns out, the movie captured the book’s subtlety of emotional expression beautifully but that was never Kazuo’s concern.

Kazuo’s hands off approach is echoed by Lionel Shriver, author of We Need To Talk About Kevin, who was quoted as saying about the adaptation of her book into a film:

“…I didn’t have a lot to do with this film. I was glad to have someone bring a different vision to something I had crafted to the best of my ability.”

Both these authors chose to adopt a hands-off approach to collaboration with Hollywood, and remain sanguine about the fact that the movie they will see will not be a slavish adaptation of the book they wrote.

I am ready for an exact close up of my book, Mr DeMille

For some authors though it is vitally important the film adaptation is as faithful as possible to their book. They are willing to be actively involved in the whole process, sometimes simply as a consultant, other times as a screenwriter, but always as close to the heart of the film’s production team as they can manage.

Sometimes this works well, with the author and those involved in making the movie finding a harmony of vision. One author who clearly fell into sync with the people bringing his book to cinematic life was Michael Morpungo, whose book, Warhorse was just released into cinemas. While he didn’t end up writing the screenplay, despite some initial attempts, he remained closely involved with the film’s production saying of Steven Spielberg who produced it:

“He was warm, kind and open, and utterly without ego…Spielberg was like a conductor with a very light baton. He hardly had to wave at all. I was in awe.”

Clearly it was a happy working relationship, and one that resulted in a successful movie. The movie does differ from the book in some respects, with the point of view moving from that of the horse to the riders, but it was obviously close enough to what he had written to make Michael Morpungo satisfied that his creation was in safe hands.

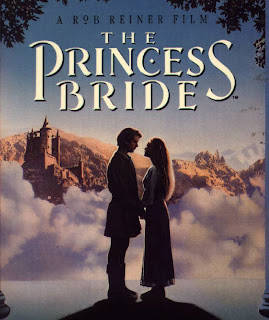

William Goldman, author of The Princess Bride, and in the unique position of being both a screenwriter and an author, also enjoyed a close collaborative approach with the producers of his book’s movie adaptation. As did Melina Marchetta, of Looking For Alibrandi, even penning the film’s script to great acclaim.

Artistic goodwill gone with the wind

But not all authors are as fortunate. Stories are legion of authors who demanded a say in how their movies were produced, got involved in some fashion only to fall out later on with the film’s producers. Clive Cussler, who was shut out the process of making his novel Sahara into a movie famously derided the movie adaptation, suing the film’s producers, which led to a protracted legal battle which has dragged on for years with neither party emerging victorious.

Similarly, Anne Rice, whose novel, Interview with a Vampire, was made into a movie in 1994 remarked “I was particularly stunned by the casting of [Tom] Cruise, who is no more my Vampire Lestat than Edward G. Robinson is Rhett Butler.” While she did eventually paper things over with the film’s producers after seeing the movie, it was only ever an uneasy truce borne, some say, of financial considerations.

But the most famous case of an author not liking his books cinematic adaptation in the least would have to be Stephen King. While the movie of his book The Shining, was almost universally feted by audiences and critics alike as a cinematic masterpiece, he detested it, despite Stanley Kubrick going to great lengths to seek his input.

One thing is clear from these examples. The success or otherwise of an author’s input into their book’s step into the Cineplex is not a given, and comes down to a complex mix of personality, artistic visions and varying degrees of iron will. If you decide you must be closely involved with the creation of your book’s movie, it may be best to remember a collaborative approach will achieve far more than a my-way-or-the-highway strategy.

The end

So now we return to the main question at hand. Just how involved should an author get when they hand their precious book over to Hollywood to get the Tinseltown treatment? It would seem that the main thing to keep in mind, regardless of whether you are happy to let the movie professionals work their magic alone, or insist on going so far as to pick the caterer to be used on set, is that the two art forms are chalk and cheese.

There is a very good reason why the “movie is never as good as the book”. It was never intended to be the book. Nor vice versa. It seems that the authors who heed that truism are the ones who emerge happiest when the world adores you, and Hollywood comes a-calling.