The clock is ticking, ticking loud and fast in J. C. Chandor’s slow-burning tale of one man’s pursuit of the American Dream, A Most Violent Year.

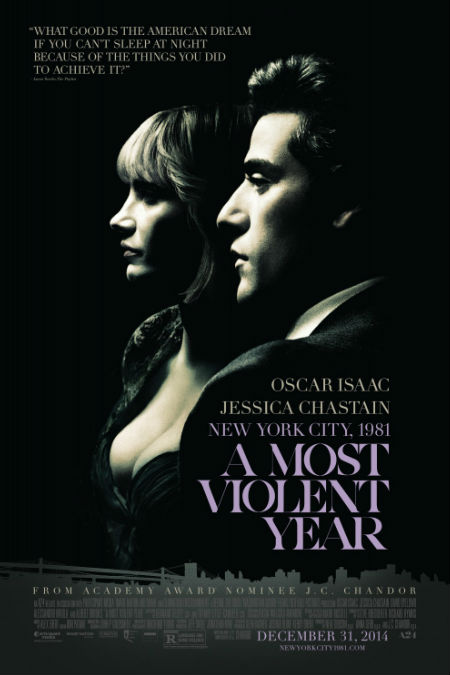

It is 1981, statistically one of the most violent in New York’s history, and aspiring businessman, Abel Morales (Oscar Isaac) is intent on turning his growing heating oil company, Standard Oil, into an empire worthy of his grand visions for the future.

To do that, he needs to complete the purchase of an abandoned fuel facility on the river, with just 30 days to find the remaining $1.5 million needed to seal the deal and a whole host of unexpected obstacles standing in his way.

Out of nowhere, and with the worst possible timing, someone is stealing his trucks, draining the oil and leaving traumatised drivers including Julian (Elyes Gabel), and a looming financial headache in their wake.

If that isn’t problem enough, the powerful Teamsters Union is threatening to pull Standard’s drivers off their trucks unless each of them are armed with handguns, District Attorney Lawrence (David Oyelowo) is filing a raft of charges against the company whose sales people are being kidnapped and roughed up before being released for daring to solicit business on other companies’ turf.

Compounding this bevy of seemingly intractable issues, is the corrupt nature of the industry in which Abel, a man of honourable intentions and conduct, has chosen to make his money and name; like much of New York at the time, the heating oil industry is has been infiltrated by organised crime whose less than honourable modus operandi is painfully familiar to Abel whose wife, the fiery but devotedly protective Anna (Jessica Chastain) is herself the daughter of a major crime figure.

In accordance with Abel’s wishes, she has largely held off implementing the tactics she grew up watching her family employ to stay ahead of the game, but with the prospect of losing everything she and Abel have fought hard to create, including a very comfortable life in an upmarket suburb, the temptation to resort to old tricks is tempting, only stymied by Abel’s edict that they will not go down that shadowy road.

There is a great deal going on in A Most Violent Year, but for all that, it remains throughout an elegantly sophisticated slow-moving drama that eschews the usual cliched narrative route for crime dramas to end up into an orgiastic inferno of guns and violence.

Instead, much like Morales himself, who stays his hand repeatedly and holds his course when everything and everyone, including his gangster lawyer Andrew Walsh (Albert Brooks) is urging him to cut loose and play ball like everyone else is, Chador holds back from heading down the expected route.

What we are given instead is a carefully-built, multi-layered, nuanced drama that pivots on the central idea that money, success, prestige and power are worth nothing if you have had to sell your soul to obtain it.

It sounds all very idealistic and out of touch with reality but lest you think this is a fairytale evocation of one man’s determination to hold onto his principles and ideals, it becomes quickly apparent that Morales will have to do some very nimble footwork indeed to create his American Dream in the image of his choosing.

In fact, it is intimated in one the final scenes of the movie with DA Lawrence, and in one key scene before that with his wife, that Morales may not not be able to stay as untainted as he would like to, that the morass of crime and corruption into which New York has tumbled in this period may yet claim his as one of its occupants, if only a partial one, and only with great reluctance.

But where he is able to, and he remains relatively more squeaky clean than any of his competitors right to the end of the film, he will build his empire through hard work, grit and determination, and bask in the knowledge that he got there on his own merits.

It is, in some ways, an intent of delusional character, something his wife, whose knows a thing or two about what it takes to make it in the cutthroat world of early Eighties New York business, points out to him over and over, with a mix of mocking frustration and grudging admiration.

But so well-written is the film, that J. C. Chandor makes you believe it is possible to bring your dreams to fruition exactly as Morales intends, that you can follow his sage advice to “take the path that is most right” and emerge a triumphant owner of your coveted piece of the American Dream.

Perhaps it is a fabled tale of immigrant success and hard work but it is worth remembering that a story such as this still holds a powerful allure, with immigrants and refugees the world over continuing to believe that it is possible to better yourself, to grab ahold of what Oprah would call “your best life” on your terms and with little in the way of compromise or less than honourable intent.

Chandor rather realistically suggests that playing the game as Morales plays it may not be an entirely feasible proposition – the dark tones of Bradford Young’s cinematography suggest pulling yourself fully away from the grey areas of life is not always possible and you inhabit them whether you want to or not – but as a study in one man’s desire to make it his way, and his way alone (Sinatra would be proud) it is a brilliantly-realised piece of drama that is as close to a morality play as our modern cynical age is likely to produce.