Films that set out to tackle the big issues of life such as death, revenge, sexual abuse, estrangement, love and salvation to name but a handful, often tread a thankless and perilous path.

They either run the risk of coming across as insufferably pretentious, too far above the day to day concerns of mere mortal man to be relatable or accessible, or too glib, so awash in black-washed humour or cleverly wry observations that they fail to engage anyone who has ever lain awake at night pondering an existence beyond grocery lists and urgent work deadlines.

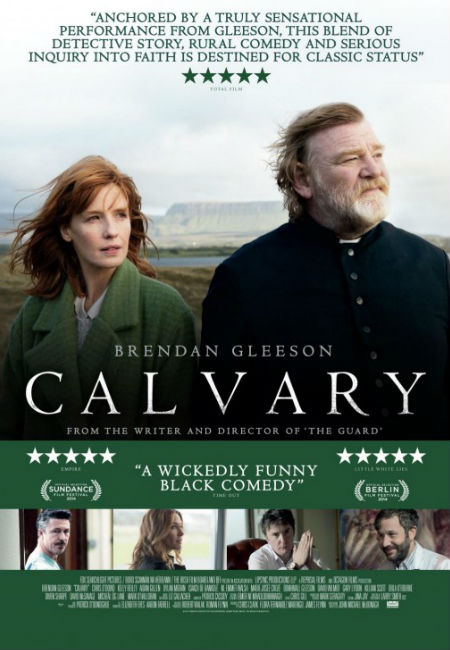

Calvary, the brilliantly-written, masterfully-executed and emotionally-affecting new film by insightful writer/director John Michael McDonagh suffers from none of these failings, instead giving us an intelligent, thoughtful treatise on the big “I” issues of life and the way they play out in the small “l” lives of the flawed men and women of small town Sligo, Ireland (whose landscape is presented in awe-inspiring, beautifully-lit grandeur, a perfect counterpoint to the darkness of the souls who call it home).

It is a sensitively rendered microcosm of the wider modern world, one in which old and once-revered institutions such as the church are now often cast in a suspect light, their authority and moral certitude all but worn away by successive scandals and publicised failings, the product of a society in which information once suppressed, now more often than not, tumbles out into the harsh light of day.

And while it is important and profoundly necessary that we are aware of these shortcomings, what is often overlooked is the way in which they have deleteriously affected peoples’ lives, the sense of loss and grief that nibbles away at the victims until only cynicism, bitterness and emotional disassociation remains.

Calvary aims to give these neglected voices room to speak and be heard through the people of Father James Lavelle’s parish (Brendan Gleeson in a toweringly impressive performance), a man referred to more than once as a “good priest”, who nevertheless bears the brunt of peoples’ disillusionment and pain, no more so than when, in the opening moments of the film he is told by an understandably embittered survivor of child sexual abuse by a member of the clergy, a man he knows, that he is to be killed in a week’s time.

Why? Because no one mourns or even notices the death of a bad priest. But a good priest? In this day and age that will attract all the attention in the world and shine the spotlight on this man’s neverending existential pain and those of his fellow sufferers.

It’s an extraordinarily confronting way to begin any movie but sets the scene for a week in which Father Lavelle, a man who entered the ministry late in life after the death of his life, inadvertently “abandoning” his daughter Fiona (Kelly Reilly), whose troubled life is another weight on this caring man’s shoulders, is forced to consider what matters to him, and to the people around him.

And frankly, they are the sort of people who would test the patience of a saint, let alone a man who though struggling with alcoholism and his failings as a father, is the closest this small town has to an honourable soul.

Whether it is the darkly cynical local doctor and atheist Frank Harte (Aiden Gillen), the butcher with a line in rather unfunny and socially inept jokes Jack Brennan (Chris O’Dowd), his flagrantly cuckolding wife Veronica (Orla O’Rourke) , her boyfriend and town mechanic Simon (Isaach de Bankolé), the aggressively angry publican Brendan Lynch (Pat Shortt), local nouveau riche gentry Michael Fitzgerlad (Dylan Moran), or sociopath-in-the-making Milo Herlihy (Killian Scott), Father Lavelle is verbally assaulted over and over by damaged, angry souls in search of someone they can take their barely concealed bitter disappointment with life out on.

Since he is, at heart, a “good priest” he wears their taunts and pejorative jabs with the good grace of any dedicated person who has committed themselves wholeheartedly to the service of others, though it is not without effect, causing him grief and exasperation that is largely, though not completely, hidden from his often nasty parishioners.

Grim thought Calvary often needfully is, it is not without its moments of black comedy, a particular trademark of McDonagh’s writing style, dressing unremittingly explosive scenes with the sort of gallows humour that is commonplace when fallible, wounded human beings attempt to deal with and process the sort of life experiences many of us hope we never encounter.

The scene where a clearly hurting but eternally taunting and sarcastic Michael Fitzgerald pulls one of his many artworks off the wall and urinates on it in an effort to get some reaction from Father Lavelle is emblematic of a movie that understands the need for some lightening of the mood to keep audiences engaged but also its power as a means of addressing issues that would be too dark to delve into otherwise.

It’s hardly a “spoonful of sugar” approach – that would be far too trite a way to treat these deeply serious issues and the fallen people over which they hold so much power – but the deftly doled out humour does emphasise how dark and damaged they are, and how insidious the failings of certain members of the church have been in damaging not just those it served but society as a whole.

Overall Calvary, which comes complete with an ending every bit as powerful as its start, is a film unafraid to be brave, to look at the looming, almost overwhelming big issues of life through the eyes of the fallible but worthy Father Lavelle, and admit that there are no easy answers, to quick fixes, no happily ever afters all the time.

It’s great importance lies in its willingness to ask the big questions, and answer them with an well-considered and far from glib affirmation that though there may be evil in this world, there is also goodness and hope (embodied in people like Gleeson’s majestically-rendered Father Lavelle), that though imperfectly expressed, is worth holding onto even if it costs you more than you could have ever expected.