There are very few genuine second chances in life.

Oh, we love to mythologise and celebrate them, holding them up as proof positive that one mistake in life does not a condemned existence make.

But as Corpus Christi (Polish: Boże Ciało) demonstrates with a quietly nuanced but furious intensity, opportunities at redemption are not only few and far between, but when they do present themselves, come with no guarantees of the Hollywood ending that is supposed to accompany these do-overs nor with any sense that you will be palpably different afterwards or even while they are taking place.

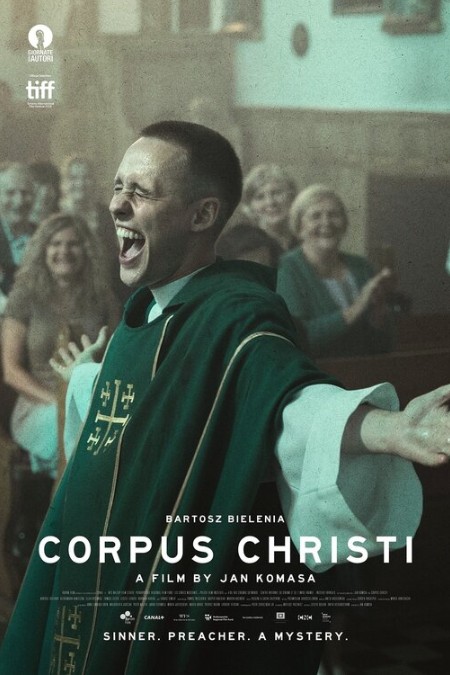

Directed by Jan Komasa to a screenplay by Mateusz Pacewicz, Corpus Christi is a powerful, emotionally resonant drama that tells the story of Daniel (Bartosz Bielenia), a young Polish man in juvenile detention for second-degree murder who has found a spiritual awakening of sorts in his adoption of devout Catholicism.

In a world that is violent and full of retribution, and where a fellow inmate known as Bonus (Mateusz Czwartosz) is vengefully stalking him for killing his brother, Daniel’s only real pleasure is assisting the resident priest Father Tomasz (Łukasz Simlat) during Mass and praying in his darkened room as the rest of the facility goes to sleep.

Above all things, Daniel wants to become a priest, an impossible future vocation thanks to the prohibition the Catholic Church seminaries have on allowing ex-cons into the priesthood – on one level it’s an understandable policy but it does ignore Christ’s entreaty to love and forgive even the worst of offenders – and so his only choice is accepting a manual job at a sawmill in a village on the other side of the country where the boss is “demanding but fair”.

Daniel arrives at the town, checks out the sawmill, immediately decides he can’t stomach working there before going to the local church where he meets Marta (Eliza Rycembel) who appears to have hung around after the final Mass.

In a bid to impress her, Daniel, who has predilection for alcohol, drugs, smoking and heavy snarling electronica, tells her he’s a priest, pulling out of his bag the priest’s shirt and collar that he carries with him as some sort of promise of an unattainable future and proof that he is what he says he is.

That one flirtatious lie sets of a remarkable chain of events as Marta, the daughter of the church’s grief-stricken sexton, Lidia (Aleksandra Konieczna) who introduces him to the church’s actual priest, Father Wojciech (Zdzisław Wardejn) who jumps at the chance to have someone fill in for him while he undergoes urgent medical treatment.

In no time at all, Daniel is fulfilling his dream of being a priest, a vocation he takes to with ease – although initial confession sessions etc. do rely heavily on the magic of Google-obtained guides – and to which, unorthodox approaches and messaging aside, he seems to have a real knack.

What sets Corpus Christi apart from its more obvious storytelling counterparts is its resolute unwillingness to take the expected route.

Sure, Daniel comes to be loved by many of the parishioners, his fresh, grounded persona and his willingness to call a spade a spade finding him many fans in a populace all too used and accepting of the religious status quo.

It seems at this point that the film will serve one of those inspiring tales of redemption against the odds, where despite the odds being well and truly stacked against him, that Daniel will win over the hearts and minds of the villagers, transform his life and theirs, and remark the world into the form he always wished it would take.

But life is rarely that straightforward or easy, and while some quite wonderful things come Daniel’s way especially as he becomes more comfortable in his adopted role, he also begins to encounter some harsh reality checks, the kind that ordinarily don’t reside in uplifting redemptive fairytales.

The mayor, played by Leszek Lichota, is the rich man of the village, used to a great deal of power and its unfettered exercise, and he is none too pleased when Daniel refuses to play along to the rules Father Wojciech presumably acquiesced to without objection.

Far more momentously however, is the effect that the great pall of grief hanging over the village has on Daniel.

The result of the death of six of the village’s teenagers in a car accident caused by a supposedly drunk older man crossing to the rock side of the road, the grief is an almost physical thing, so omnipresent that it corrupts just about everything it touches from the way Lidia humourlessly executes her duties to her soured relationship with Marta and on to the persecution of the driver’s widow (Barbara Kurzaj).

It is near escapable, leaving Daniel with not much option but to tackle it in some way, which he does but not in the way you might expect.

Drawing from his own considerable wellspring of grief, pain and loss, Daniel initially manages to bring some healing to the parents of the children and to the village as a whole.

It’s necessary work because it is obvious to everyone other than the people mired in grief (save for Marta who, although she grieves the loss of her brother Jakub with every fibre of her being, won’t play her mother’s hate-filled game) than the grief, while understandable is corroding the emotional and mental wellbeing of the church, and that while Lidia claims they are all “good people”, the reality on the ground would suggest that goodness is in the eye of the beholder.

In the end, Corpus Christi, which is at all times, thoughtful and empathetically observant of the human condition, doesn’t go down the expected route, eschewing what we might expect to happen in favour of something altogether more resonant and real, an ending that acknowledges that while second chances and the redemption that might come with them is possible, they rarely play out as expected and may not necessarily given the wholly happy answer you are seeking.