There is a particular kind of film at which the British film industry excels at an order of magnitude greater than pretty much anyone else on the planet.

In these movies, a person has variously fallen on hard times/lost their way/had long-held assumptions shaken and find themselves almost catastrophically adrift, unsure anymore of who they are or where they belong.

Unsure of where to turn, they find themselves returning to estranged family members/long ago left behind hometowns/forgotten friends in a bid to find a safe haven and reinvent their lives which they do in almost inevitably heartwarming fashion.

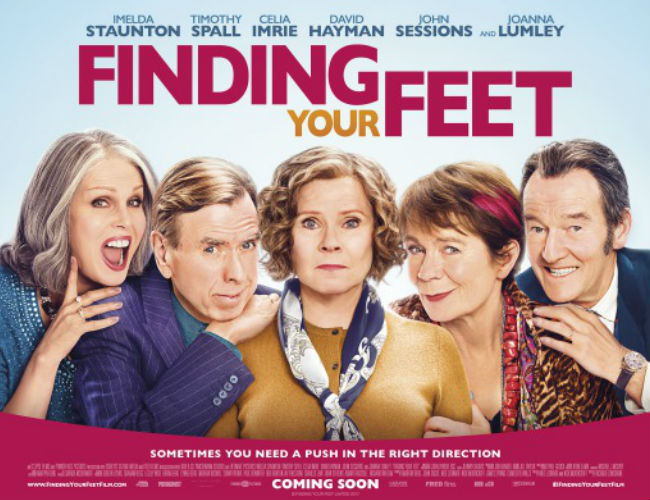

The genius of these films, of which Richard Loncraine’s Finding Your Feet is a superlative member, is that for all their trope-heavy, cliched feel-good elements and guaranteed happy endings, they somehow manage to still feel grounded and real.

It’s no easy balance, but one these films seem to pull off with almost blithely efficient ease, giving us a look at both the brutal realities of life but also, more importantly, the promise of restitution or redemption, something not always guaranteed in the crash-and-burn unforgiving argy-bargy of everyday life.

In Finding Your Feet, the screenplay by Nick Moorcroft and Meg Leonard gives us the classic British feel good film in all its whimsically harsh glory, offering us both the worst of life and the very best of life, if only the characters will be open to it.

At the start of the film, when her marriage to her husband of thirty-five years Mike (John Sessions) breaks down, foundering on the rocks of his long-hidden adultery, Sandra (Imelda Staunton) is open to nothing of the sort.

Looking forward to a leisurely retirement touring Europe and playing tennis with the rest of her upper class social clique, and buoyed by her husband’s recent knighthood, thus elevating her to the rarefied position of Lady Abbott, Sandra is, in her own words, “destroyed”, unable to imagine any other life than the one cruelly snatched away from her.

At this point, the idea that anything else worthwhile might be on offer is impossible to imagine, and Sandra spends much of the early part of the film, after moving in with her estranged bohemian sister Bif (Celia Imrie), drinking, being obnoxious and sullenly objecting to the very idea of doing anything other than stewing in her own misery.

We’ve seen it all before, and we all know it’s merely a set-up for a wondrous, if grudging, journey of illuminating self-discovery but Staunton and Imrie, and Timothy Spall as Charlie, Bif’s friend, make it all very real and turbulent and chaotic, just like it would be in real life.

Granted it’s not an exercise in cinéma vérité but then it’s not intended to be; this is escapist filmmaking after all.

But it does neatly capture how wrenching it is to have your life unceremoniously upended and to see no option but to rail, loudly and with fury, against the world.

We’ve all been there to some degree or another at some point or another, and Finding Your Feet captures the resultant emotional free fall with the kind of authenticity that adds substance to a film that could easily possess nothing of the kind.

You know the moment the film starts that Sandra will, yes, find her feet again, that a semblance of normality will be restored and life will beckon with glittering new options that will trump everything that has gone before.

And lo that is indeed what happens with sisterly relations not just patched up but reborn, love rediscovered with Charlie, who is given a poignant story of his own (which is employed to generate the necessary final act misunderstanding, precipitating the inevitable happy-ever-after rapprochement) and a new lease of life duly procured thanks to a dancing club where Joanna Lumley as five times-married Jackie, and widower Ted (David Hayman) provide humour and pathos in equal measure.

In one sense, of course, you’ve seen it all before, with Finding Your Feet hewing to a template almost as old as films itself.

And yet, for all that familiarity, the film feels fresh and vital, a delightful excursion into the very appealing idea that not only can you recover from cataclysmic events in life but you can emerge feeling, looking and acting even better than before.

Fairytale-ish it may be in many respects, but done as well as Finding Your Feet is, and it is done gorgeously, exceptionally anchored by a phalanx of brilliantly good, measured performances, you hardly begrudge leaving the cinema feeling so exceptionally good and inspired, assured that only are leaps of faith a good thing but damn near necessary for a healthy, true-to-yourself life.

The film is proof positive that it is possible to take a well-worn idea and take it for another run around the cinematic course, and while not reinvent things to any kind of astounding extent, create something so ineffably charming, cosy and heartwarming that the twists and turns of life, many of them to places you don’t want to go to, don’t see anywhere near as threatening anymore.

The appeal of films like Finding Your Feet is clear – they often give us what we don’t always get in life, and in a world where happy endings are increasingly looking like the stuff of myth and legend, that’s not such a bad thing at all.