War is hell.

That much we know to be true from firsthand accounts, documentaries, books and a seeming never-ending succession of movies and TV series, and in a sad sign that little has changed, from current nightly news broadcasts, all of which speak of its nightmarish horrors, its soul-destroying inhumanity, its ruthlessness suppression of the nobler instincts of our collective character in favour of death and destruction.

The question then is whether David Ayer’s Fury, which he wrote and directed and which doesn’t flinch from portraying war in all its gruesome depravity and unavoidable brutality, really adds anything to this ongoing, vitally important, conversation.

Not that it necessarily needs to of course but movies focused on a time of war, particularly those focusing on the two World Wars our planet has endured, can’t help but take on a thematic weight far in excess of what their dramatic intent might be, and Fury is no exception to the rule.

And the answer unfortunately, despite its obvious intentions to be that and more, is no.

For while it ably explores how harrowing an experience it must be to be asked to kill your fellow human beings, and what a traumatic departure from the relatively benign business of 9-to-5 living it is – we see this most effectively addressed in the person of US Army Private Norman “Machine” Ellison (Logan Lerman), a young typist who finds himself unexpectedly on the frontline with little to no warning or training – Fury sacrifices any real sense of the emotional impact on those called on to commit these acts in favour of depicting them in all their stomach-churning glory.

It’s an effective approach if you are looking to get a sense of what war can do to a person, and how destructive it can be to their sense of self, and the way in which they relate to others but not so effective if you are looking to examine, as Ayers claims to be, on the nature of “family” and the way people intensely bond in unusually perilous situations such as a theatre of war.

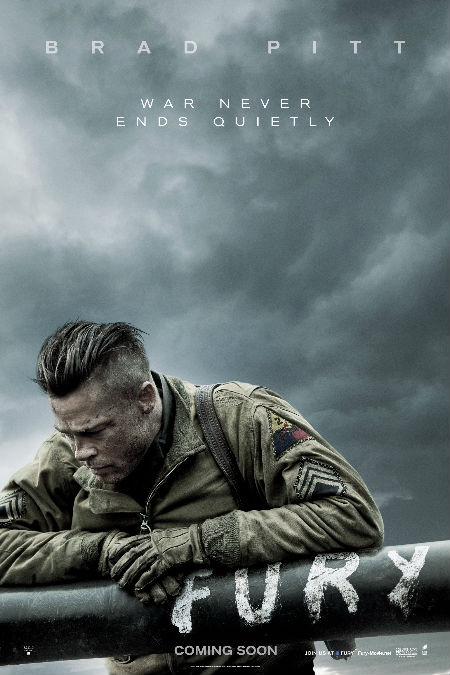

This is not to say that the tank crew of the US 2nd Armored Division which Ellison joins in April 1945 in the dying days of the Allied advance across Germany, led by brusquely tenacious Staff Sergeant Don “Wardaddy” Collier (Brad Pitt in fine nuanced form), and which includes Shia LaBeouf as US Army Technician 5th Grade Boyd “Bible” Swan, Michael Peña as US Army Cpl. Trini “Gordo” Garcia and Jon Bernthal as US Army PFC Grady “Coon-Ass” Travis, aren’t a family.

Bonded in battles that have extended for three years across Africa, France, Belgium and now the homeland of the murderously infamous Third Reich, they are as much family as anyone can be, a highly fractious, sometimes downright antagonistic dysfunctional one, but a family nonetheless.

Moving forward solely on the sacred vow that Collier has made to get them all home in one piece – there is no evidence of the noble patriotic drive that seemed to fuel Saving Private Ryan or Band of Brothers; Collier and his men are there to get a job done – they do not take kindly as first to the entry of Ellison to their number, a man who ends up killing multiple score of enemy soldiers on the front line in the course of witnessing unspeakable horrors.

Through the young recruit’s eyes, we see masses of the dead being interred with little formality or sentiment into mass graves, men caught in exploding tanks aflame, whose only escape is a self-inflicted bullet to the brain, and civilians, in the wrong place at the wrong time, bombed or gunned down with little fanfare, and even less mourning.

It is nasty, brutal and unforgiving, extending little time to the uninitiated like Ellison to adapt to its unpredictably violent demands.

It asks a great deal of a person, of a team,which is why Collier (who we do see in one all too rare moment privately grieving his lost comrade), frustrated that his newest team member isn’t getting up to speed as quickly as he would, that he is flinching at the idea of killing the enemy, “bloods” him by forcing him to kill a captured German soldier in close quarters.

It has the desired effect of forcing Ellison to lose his innocence, and reminds us once again that it is a dog-eat-dog, kill-or-be-killed world when you’re at war, but something of Ayer’s exploration of family is lost in that moment, if it was ever fully, authentically there in the first place.

The inherent failing of Fury, for all its dramatic bombast and visually shocking moments, of which there are many, is that it loses any real sense of humanity in the process of being the most authentic war movie it can be, unable to fully establish what it is that bonds the five man of the tank together in any meaningful fashion.

True, they speak of working towards Collier’s goal of getting them home in one piece to their loved ones, but theirs is ultimately a false, almost hollow, camaraderie, one in which the words are spoken, the deeds done but with no real sense that these men actually care for each other, not in the way it is suggested they do.

This leaves the audiences curiously emotionally uninvolved in the final climactic scene when all of this great bonding, this family of brothers is put to its final, greatest test.

There are moments of great determination and resolve, and real anguish but these are sapped of their power to a large degree, despite the swelling, highly emotive and downright eerily beautiful score of Steven Price, by characterisation that is nowhere near as sharply defined, or well lived out, as it could be.

For all its arresting visual power and awe, its stark lessons on the darkness and futility of war, its sometime poignant interludes – the meeting of Ellison and a German girl Emma is especially affecting – you are left at the end of Fury feeling curiously empty and unmoved.

It is not quite sound and fury signifying nothing but it comes awfully close.