Films, by and large, and this is by no means a hard and fast rule, either fall into two distinct camps – those you watch and those you experience.

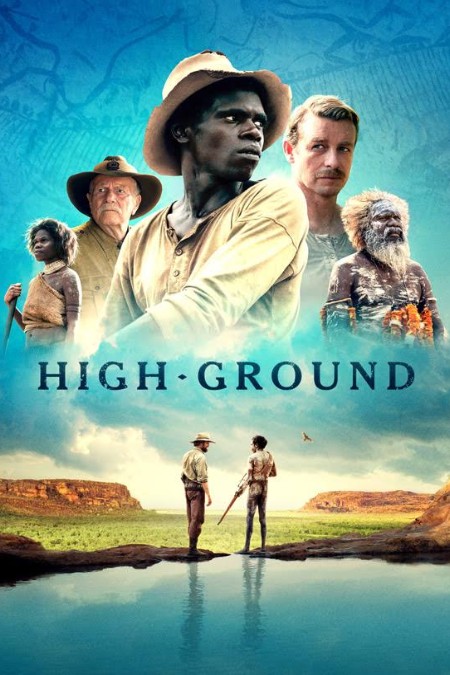

High Ground, a superlatively affecting Australian film, directed by Stephen Maxwell Johnson to a screenplay by Chris Anastassiades (from a story by Chris Anastassiades, Stephen Maxwell Johnson and Witiyana Marika, most certainly fits into the second category, a powerful statement of loss, dispossession, violence and cultural and familial degradation that takes some very big, resonant issues and brings them down to a very intimate, gothically poignant level.

Set partly in 1919, and for the most part in 1931 or so, High Ground is a breathtakingly brilliant and searingly evocative exploration of what happens when a manifestly unjust and destructively tragic event takes place, leaving hatred and lingering, corrosive loss in its wake.

Pulling no punches, and yet telling its story with powerful nuance and an eye on the innate sorrowful humanity of it all, the film pulls back the curtain on Australia’s blighted, violent past, underscoring yet again how horrifically poorly the country’s First Nations people have been treated by people who continued then (and sadly often now) to rule with a racist, colonial mindset long after the initial invasion and forced settlement of the country.

There is no way, of course, that one film could deal with such a gargantuan, festering issue and High Ground wisely does not attempt to; instead, it takes us deep into the lives of two interconnected men – police sniper and ex-World War 1 digger Travis (Simon Baker) and Gutjuk aka Tommy (Jacob Junior Nayinggul), a survivor of the aforementioned tragic event whose full extent is best left to the watching of the film.

(Suffice to say, it begins High Ground as it means to go on, bathed in violence, blood and a suffocating sense of endless oppression and cruelty.)

These two men couldn’t be more different in certain ways but thanks to a bond forged when Gutjuk is just a boy, when he is brought to the East Alligator River mission and remanded into the care of Claire (Caren Pistorius) and her preacher brother Braddock (Ryan Corr), they share some common ground which is pivotal later on in High Ground when a now grown Gutjuk is asked to help a police party, led by Moran (Jack Thompson) and violently impulsive and odiously racist Eddy (Callan Mulvey), find his uncle Baywarra (Sean Mununggurr) who is charged with burning down settlers’ farms and killing a white woman.

This places the gentle young man, who works on white men’s properties like many of his clan in conditions that are close to slavery rather than full, just employment, in an invidious position, forced to choose between protecting one of the few remaining blood relatives he has left alive, and playing his part as a member of white society (although, as he and every other First Nations people are constantly reminded, it is an oblique membership at best and certainly not one on which he can place any weight of certainty lest it collapse beneath him in a welter of racism and palpable scorn).

It’s at this point that you might think you know exactly where this cleverly-written and artfully, spectacularly shot film will take you but you would be very, very wrong.

High Ground is never content to follow the expected route at any point, and with a wily inventiveness and willingness to lay all its brutalist but affecting cards on the table, it sends the narrative off on a path that shakes you to your very core.

What is remarkable about the film is that rather than losing itself in a morass of big action pieces – they are most certainly there and they are arrestingly shocking and utterly, heartstoppingly immersive – it invests them with raw, intimate humanity, the kind that never fails to understand that at the heart of every big story, every towering issue, there are people trying to live their lives and make sense of it all.

In the case of Gutjuk, who is played with immense power and subtle thoughtfulness by Nayinggul, it is how you reconcile being a part of two worlds, and how you deal with a terrible choice – do you surrender to vengeful fury, as Baywarra’s associate Gulwirri (Esmerelda Marimowa), urges an uncertain Gutjuk, or do you listen to father sky and mother earth and embrace calm as the young man’s grandfather, Grandfather Dharrpa (Witiyana Marika), says, with kindness and understanding, he would be best to do.

It is an impossible choice and watching Gutjuk wrestle with it, when every scion of his spirit and soul, heir to almost 150 years of loss of Country, life and culture by his fellow First Nations people, says to strike back, is powerful beyond belief.

Set against the spectacular backdrop of Kakadu National Park in northern Australian, High Ground is a film which doesn’t offer easy answers nor does it pretend that you can solve these issues quickly or easily or heal long festering wounds with next to no consequential messiness.

This film, which places First Nations culture, from its language to music to its close bonds to family and Country, front and centre, is one which, apart from tell an enthrallingly gripping story of loss, revenge and squandered, wasted possibility, is a revelatory endeavour, seeking to expose the dark underbelly of Australian history so that, hopefully, some healing might come.

Certainly, in the context of heated debate about Australia Day vs. Invasion Day and the declaration of the Uluru Statement of the Heart, and overall need for Australia to face up to its bloody and violently racist past, High Ground‘s release is timely.

It is a film which does not pretend everything was, or is okay, it is clear that there are no easy answers to entrenched, cruel prejudice and rampant colonialist injustice and that true reconciliation and healing can only come when the truth is revealed, faced up to and we understand the depths of the wound that must be addressed in a country with more blood on its hands that it would care to admit.