Whoever coined the empty, almost universally quoted retort to bullies “Sticks and stones may break my bones but names will never hurt me” was clearly lacked in some form of meaningful self-awareness.

The truth is that while our bodies can usually repair themselves physically in fairly short order, the damage to our psyche lasts far, far longer if it ever heals at all.

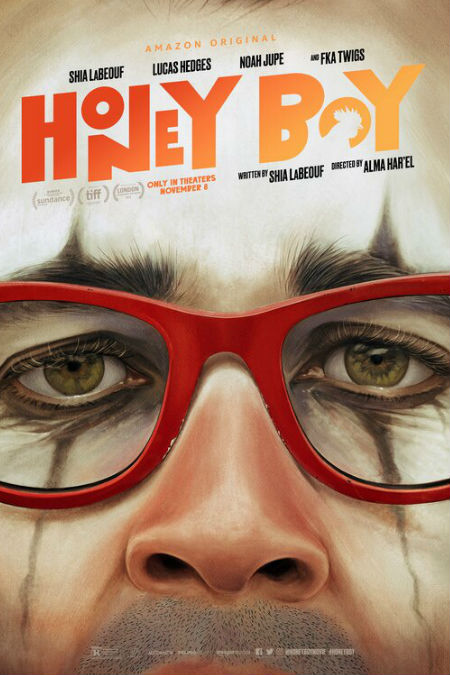

Testament to this is Otis Lort (Noah Lupe as Otis aged 12 and Lucas Hedges as Otis aged 22) the protagonist in the Shia LaBeouf penned, Alma Har’el directed film Honey Boy who continues to suffer greatly a decade on from unremitting physical and emotional abuse of the hands of his father.

A child actor in great demand, Otis is doing well enough from his acting career to employ his father as his chaperone, the only job that convinced sex offender James Lort, who juggles intermittent drug and alcohol addiction and volcanic anger issues, is able to get.

Otis desperately wants a father, and while his mother is in the picture – presumably back home though it is never made clear where she is and why she continues to let her son stays in a palpably dangerous situation – his need is so great that he puts up with significant levels of near continuous abuse.

Switching between 22-year-old Otis in 2005 and 12-year-old Otis a decade earlier, Honey Boy examines in a quietly methodical but immensely emotionally powerful way how abuse leaves scars that are profoundly destructive to our wellbeing and all but impossible to eradicate (unless, of course, we are willing to which older Otis clearly is not; not initially, anyway).

In rehab once again after his third DUI incident, which not only threatened his life but that of his passenger, Otis admits at one point that he finds it near impossible to let go of his deep-seated pain because it is the only thing of value his father gave him.

How’s that for a stinging indictment of a father’s parenting performance?

Otis the elder is clearly in pain, unable to process what happened to him and so caught up in the “lie” of acting – he’s been doing it since he was a kid so it is second nature to him to dissemble and project what his audience, in this case his court-appointed psychologist Dr Moreno (Laura San Giacomo), wants to hear – that he does habitually, to his own lasting detriment.

A semi-autobiographical movie based on Shai LaBoeuf’s own experience growing up – the title comes from his childhood nickname – the film swells in its own quietly understated way with pain and loss and the inability of Otis to navigate away from the one relationship in his life that really meant something to him.

The fact that it was the most toxic one is something he recognises now, and to be honest, recognised then – his attempts to confront his father about the way he is treated always end with a fiery outburst and an unwillingness to acknowledge he is in any way at fault – but he is unable to let go off it or its virulently damaging effects.

That is until the perfectly-judged ending which provides a closure which may not be cited in many psychological journals but which is one which meets Otis exactly where he is and makes use of his near-lifetime experience as an actor.

What makes Honey Boy so startlingly compelling is the consummate way in which it deftly wraps a deeply-affecting story of abuse and near-non-recovery, of brokenness, pain and loss of direction in a quietly unfolding story that, part from a few scenes of ratched-up emotional or phsyical violence, never raises its voice to anything approaching a melodramatic pitch.

It tells its story as a series of interconnected scenes, all of which shed light on Otis’s current affliction but in a way which unfolds the quiet misery and introspection that is his lot.

His is a life that by all appearances is bright, bold and cinematically alive.

Honey Boy in fact begins with a manic montage that feverishly switches between the on-set filming and between scenes reality of Otis, only coming to an end in the aftermath of his latest near-fatal car accident.

From that point on, the film beautifully contrasts the yawning gulf between the quiet desperation of Otis’s quietly-tortured off-screen life and his public persona which pays no heed to his loneliness, isolation, alcoholism and drug taking.

Moving between Otis’s current stint in rehab and his emotionally-anguished time as a 12-year-old living in a rundown motel with a father who is supposedly there to protect him as his chaperone but who is more than a threat than anyone else in the young man’s life.

The only real connection Otis has is with the somewhat-similarly damaged older teen girl from across the motel’s courtyard, Shy Girl (FKA Twigs) who reaches out to him, sensing a kindred spirit in need of the company of someone who truly understands.

Though there is an undeniable sexual element to their moments together – thanks to James’ manifest deficiencies as a father and a human being, Otis is allowed to run wild, smoke cigarettes and even sample weed – their true worth to each other is as empathetic companions through the hellish existences they are living.

Otis is in the end damaged badly by his childhood to such an extent that his early adult years are scarred beyond recognition with a thousand cuts borne of emotional denial, a lack of boundaries and love and a desire unfulfilled to have a father who actually lived the part.

The film is in many ways a slow, touching walk towards healing, though that is not immediately apparent until almost the last scene, one strewn with the ghosts and touchstones of Otis’s past and told in a highly-creative way in which dreams and memories meld seamlessly with current reality to devastatingly moving effect.

Honey Boy is brilliant – inventive, idiosyncratic storytelling that packs a quiet but supremely powerful emotional punch as it explores the troubled relationship between a boy who desperately wants a real dad, an alcoholic, broken dad who has no real idea how to be a father, and the seemingly irreparable void it creates between childhood pain and adult existential despair and the long road to a place where the two are no longer damagingly connected and life might be able to begin again.