For a species known for its inquisitiveness and love of freedom of expression, humanity, at least the more authoritarian parts of it which are far too commonplace for anyone’s liking, has an enduring liking for enforcing spirit-constraining rules on itself.

Perhaps they made sense once upon a time when threats were numerous and resources scarce, but now they simply seem like cruel and mean-spirited vestiges of a time long past that have no real place in our modern, ever-changing world.

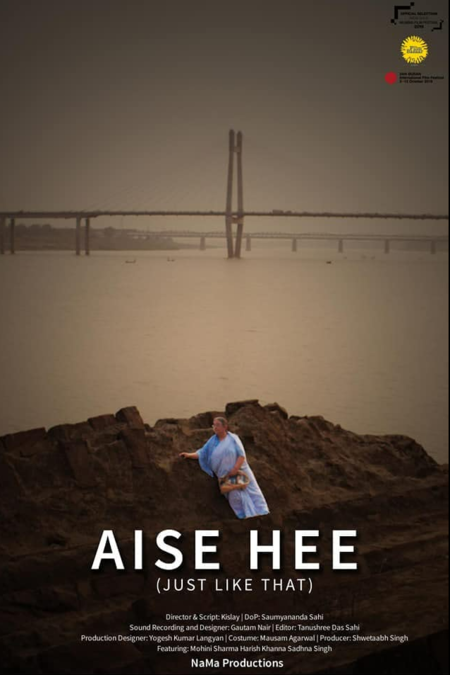

Just Like That (Aise Hee), which was delayed in its release, like so many other films, by the COVID pandemic challenges these types of long-held rules and traditions head on, asking a simple question – if it’s not hurting anyone, why can’t a particular path be followed in life?

Mrs. Sharma (Mohini Sharma) is recently-widowed, a quiet woman who has spent the last 51 or 52 years subsuming her needs to those of her “always busy” husband, never really allowed to have a life of her own except for when its crossed over with that of her spouse’s.

Living above her son Virendra (Harish Khanna) and his wife Sonia (Sadhna Singh), and grandchildren Vicky (Shiram Sharma) and his sister Vinny (Saumya Jhakmola), Mrs. Sharma is a woman trapped with a suffocating web of expectations from which escape, if anyone even dares to use that word, is all but unthinkable.

In this rigid world of thinking and harsh social expectation, Mrs. Sharma is supposed to compliantly move in with her son in the apartment one floor below, where there is precious little scope for any freedom or independence – that is, of course, the point; she isn’t allowed to have any part of her life unconnected to that of her son and his family – and simply exist, any semblance of uniqueness or individuality consigned to the scrapheap of feverishly impossible dreams.

It’s not much of a life, and both Sonia and Vinny are painfully aware that it is likely to be their end too, and any deviation from it must be the result of possession or madness as the local neighbourhood group of official busybodies in the Colony section of Allahabad or Prayagraj, makes judgementally clear.

Mrs. Sharma though is having none of this.

Quietly and methodically, and with liberatingly joyful intent, she sets about making life in her own image, going to the shopping mall for an ice cream, learning how to embroider from the local single elderly Muslim tailor, Ali (Mohammed Iqbal) and going for excursions to the cool of the river with beautician Sugandhi (Trimala Adhikari), many years younger than her but full of the same need to be herself and live a life unconstrained.

Watching Mrs. Sharma, who rather deliberately is referred throughout only by her married name, reinforcing the prevailing message from writer-director Kislay of identity only through patriarchy, come alive is one of the many quiet joys of this nuanced and insightful film which doesn’t so much shout revolution as it does whisper it fiercely from the margins where the movie’s protagonist is often consigned.

In her newly-made world, she can go to the riverbank at night with Sugandhi and watch the stars twinkly overhead, she can open her own bank account and look after her own money – something which confounds her easy-to-anger son who can’t understand why she simply doesn’t submit to his oversight like her husband did – and find creative fulfilment in sewing items simply for the pleasure of doing so.

But stirring the hornets’ nest doesn’t come without some stings back, and soon enough, the fossilised, unthinking powers that be in the neighbourhood rally and set about, with a ruthless efficiency that matches the best from a totalitarian state or an overly-enthusiastic American homeowners association from a sitcom or drama, to pushing Mrs. Sharma’s square pig back into their ill-fitting but “proper” round hole.

You know it’s coming but watching her newly-formed, freed life which is coming into its own in ways that delight the heart of anyone who has ever longed to pull away from the strictures of hidebound thinking, is sorrowful and infuriating, happening with a speed and cruelty that stand in stark contrast to the simply and uncomplicated that the film’s lead character has fashioned for herself.

With expansive shots across the city she calls home, courtesy of director of photography Saumyananda Sahi, and visual and aural style that accentuates the rhythms of a city that has only has time for the likes of Mrs. Sharma if they play along – by way of pointed contrast, it is clear that Mrs’ Sharma’s new life is hurting no one and the city and its surrounds are uncaring about whether she breaks the rules or not – Just Like That (Aise Hee) is a rallying cry to find and fight for yourself, even as it sagely and soberly observes, with a crushing sense of inevitability, that such fights rarely end in a win, or at least, an unfettered one.

Anchored by Mohini Sharma’s evocatively nuanced performance as a woman deeply unhappy about her old life, quietly happy with her new one, and made miserable when it taken away from bit-by-bit, block-by-condemnatory-block, the film is an intelligently and empathetically wrought film that takes cares not to paint anyone as a caricature, save for the “concerned” neighbours who can’t come across as anything other than hackneyed relics from an age that should be bygone but which is quite patently not.

Even Mrs. Sharma’s son is shown to have some layers to him, a man beset by his own subsumingly constrictive hierarchical expectations and stymied dreams who is lost in his own world of failed hopes, much like his wife Sonia, and children who seemed destined to repeat the mistakes of their forebears simply it appears because the adverse reaction to Mrs. Sharma’s bid for independence gives them no choice.

While Mrs. Sharma does find herself pushed back unceremoniously into a box she does not want to inhabit, the great strength of Just Like That (Aise Hee) is the hope it carries that things can change, that people can free themselves of mindless societal expectations and that being yourself is a thoughtfully quiet joy, not some outward manifestation of demonic possession.

Unspooling its message with sensitivity and care but with a necessary and timely pointedness, Just Like That (Aise Hee) is an immersively affecting film that intimately explores what new-found freedom is like, standing its vivacity and hopefulness in stark contrast against the moribund social conventions of the day that serve no one well and which doom people like the graciously brave Mrs. Sharma from living a life that is uniquely and satisfyingly theirs.