Anyone who has ever experienced any form of profound loss will know all too well that grief is a peculiar, never ending lament with a thousand different reminders everywhere you turn.

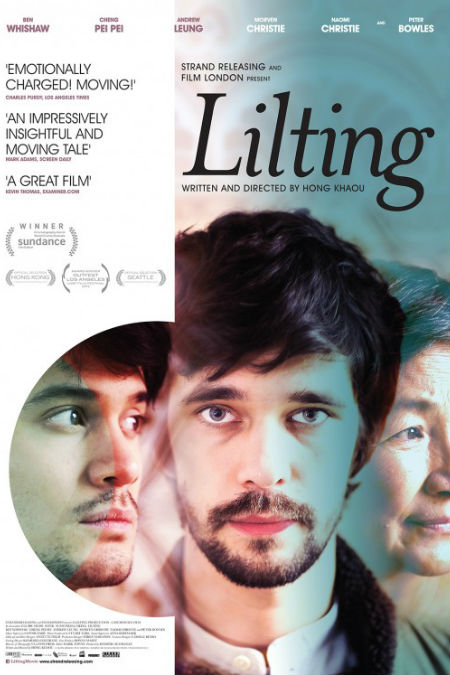

The truth of this painful reality is authentically conveyed in starkly moving, intimate terms in Hong Khaou’s largely assured debut feature, Lilting, a film that understands all too well that you never truly “get over” the loss of someone you loved with all your heart.

This understanding of the power of grief to inform every last facet of your existence informs the lives of Richard (Ben Whishaw) and Junn (Cheng Pei-pei), the partner and mother respectively of Kai (Andrew Leung) whose sudden death at the hands of a “c**t of a driver” has left the two most significant people in his life in emotional limbo.

Both Richard, who remains in the flat he and Kai called home – a place his partner largely ordered and decorated, another daily reminder of the loss he has experienced – and Junn are desperately searching for meaningful ways forward, ones that allow them to hang on to the memory of the man they loved deeply.

But as anyone with a heartbeat knows, this is far easier said than done, and in the case of Richard and Junn, complicated by the fact that Kai hadn’t yet come out to his mother at the time of his death.

So Richard remains in the relational shadows, still tagged with the appellation of “friend” by Cambodian-Chinese Junn who fully confesses she didn’t like the man her son shared a home with, seeing him as a threat to her almost wholesale dependence on Kai who helped help her to navigate life in her adopted home country, the United Kingdom, a country whose language remains a mystery to her decades on.

Imprisoned by their unrelenting grief – for Junn, who resents bitterly the perfectly lovely retirement home she was moved into not long before her only child’s passing, it has taken on a physical form – they are left to replay their last conversation with Kai, imagining over and over what it would be like to have him with them one last time.

Pushed to the point of breaking by Kai’s loss, and so understandably emotionally fragile that tears are never far from falling, Richard decides that the way he is going to be able to press forward with his life is to forge some form of connection with Junn.

Armed with impractical idea of asking Junn to move in with him, a wildly improbably possibility made perfectly, delusionally reasonable by the distortions of his grief, he enlists Vann (Naomi Christie), a non-professional translator with whom he becomes friends, to build a bridge of sorts between Junn and himself.

Realising though that this might be a little too confronting for Junn, who wonders more than once why her son’s “friend” is going to so much trouble to help her and what his ulterior motives might be – they are surprisingly pure and self-sacrificial but Junn isn’t privy to this – he offers his and Vann’s assistance to translate for the budding relationship Kai’s mother is enjoying with Englishman Alan (Peter Bowles).

While this starts out as the ostensible reason for Richard’s presence in Junn’s life, the two eventually form a faltering bond, one often interrupted by misunderstandings of intentions, connections and motivations, and the wide, almost uncrossable cultural chasm between them, one only slightly bridged by Richard’s ability to cook deliciously authentic Chinese cuisine.

Hampered all the way through by that last crucial unshared but utterly crucial piece of Kai’s identity, Richard and Junn dance around each other, each clutching their grief and their unvoiced last thoughts to Kai close to them, many of their most honest thoughts left untranslated, at their request, by Vann who is often caught uncomfortably in the middle of their attempts to relate to each other in some form.

What truly sets Lilting apart, quite aside from its delicate addressing of both the chaotic tumult and emotionally-entrapping nature of grief, is the gentle, unhurried way that Khaou goes about telling this often quite touching tale of two people separated by language and culture, their own interpretations of who Kai was, and their all-too-human fumbling attempts to deal with his departure from their lives.

Khaou, working off his own finely nuanced script, lets the story meander along, its often fraught but also sometimes humourous, scenes – Alan and Junn, for instance, often find Vann’s presence as their interlocutor intrusive and un-conducive to possible love, true love – punctuated by cinematographer Urszula Pontikos’ beautiful, stark sweeps of frost-covered, tree-filled landscapes which visually match to an unsettling tee the isolation and sense of desolate loss felt by Junn and Richard.

Whishaw is immensely moving as a man wallowing in grief untold, his mourning escaping unbidden at key moments when a stray question from Junn, unaware of the depth of Richard’s connection to her son, pokes a little too closely into his usually well-hidden wounds, while Cheng is mesmerising as a woman, trapped in a Russian nesting doll of various emotional and cultural prisons.

While Lilting may sound unremitting bleak and uncomfortably sad, and to be fair it is at times, a natural occurrence given the subject matter explored, it is first and foremost a poignantly touching portrayal of two people, separated from each other, trying hard to create a connection through which their shared memories of the man they loved more than any other might finally find an audience.

While the ending is deliberately ambiguous in terms of whether Vann actually translates the home truths finally shared – I suspect not although Khaou rather cleverly leaves that to our own interpretation – there is a sense that for all the obstacles in their way and the unintended missteps along their shared journey, many of them wrought by the grief that warps what you suspect they would normally say and do, that Richard and Kai do reach an understanding of some kind, a shared sense of loss and quite possibly, a way forward out of the seemingly endless mire of their grief.