There is a point towards the end of Moonlight, an achingly poignant examination of identity, loss and love, that you realise how much damage can be done to one person’s sense of self by the thoughtless words and ill-thought-out deeds of those closest to them.

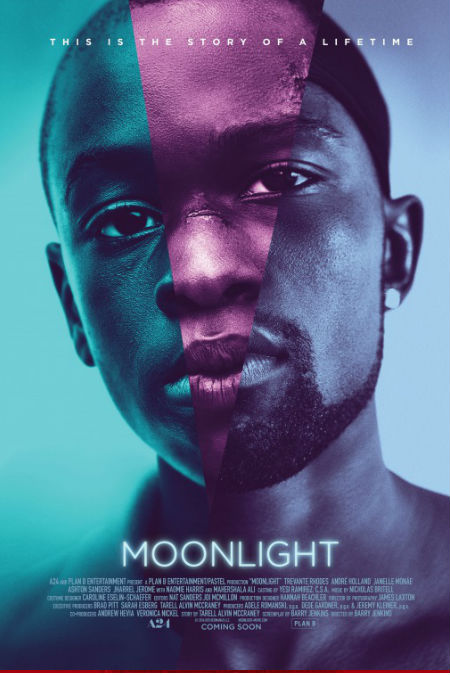

Chiron (Travant Rhodes as an adult / Ashton Sanders as a teenager / Alex Hibbert as a child), the film’s protagonist, has finally returned home to Miami after 10 years away, ostensibly to see his mother but more especially, to reconcile with his childhood best friend Kevin (André Holland as an adult / Jharrel Jerome as a teenager / Jaden Piner as a child) with whom he enjoyed an all-too brief relationship in his teens.

When Kevin expresses surprise that the slim, cowering teenage Chiron has morphed into a hardened, muscled-up drug dealer named “Black” (Kevin’s old nickname for him), Chiron snaps back that Kevin couldn’t possibly know who he really is, which elicits a soft assurance that he does know who his friend is and the person before him is not him.

It’s a touching riff on a theme that percolates throughout the film, triggered by a simple “Who is you?” question to Chiron when he is a boy, and goes to the heart of the film’s insightful exploration of how deeply identity can be shaped by the words and actions of others.

In Chiron’s case, the influences have been profound, and rarely for the better with his crack-addicted mother Paula (Naomie Harris) about as far from a loving maternal figure as you could ask for, and more prone to belittle and attack her son than nurture and encourage him to be himself.

Her actions, which create an incredibly unsafe environment for Chiron, who is known as Little as a child – the film is divided into three parts, charting the character’s childhood, teenage life and adult life – are made all the worse by a chaotic school situation where the sensitive young man is bullied repeatedly and with violent vigour by a gang led by Terrell (Patrick Decile).

With no safe place to retreat to, save for occasional nights at the home of Theresa (Janelle Monáe), the girlfriend of a drug dealer Juan (Mahershala Ali) who for a time acts a surrograte father figure for Chiron, the young man is constantly under siege, never able to let his guard, and certainly never able to be himself.

This, as you might expect, has a corrosive effect on him, with the suppression of his true identity – he is at heart, a quiet, thoughtful, introspective soul) – eventually leading to the sealed-off drug dealer that Kevin challenges in the gentlest of ways in that pivotal final scene.

Sensitively and thoughtfully handled, thank to expert direction by Barry Jenkins, who also wrote the screenplay based on In Moonlight Black Boys Look Blue by Tarell Alvin McCraney (the two men grew up close to one another in the same Miami neighbourhood), it becomes apparent over the three stages of this nuanced film, which is almost as quietly-articulated as its protagonist, that the loss of identity can have a profoundly negative impact on a person.

This rings true for anyone who has been beaten down, either at home or school growing up, and has had to retreat into themselves, afraid to open up or vulnerable lest it grant their enemies an opportunity to inflict yet more damage.

When your identity is broken away bit by bit, piece by piece, and you are only ever able to present the small possible target to the world, your sense of self shrinks along with any expression of who you truly are.

This is painfully, and desperately movingly true of Chiron whose adult self shelters the sensitive young man he once has, someone who has been locked away for many years until Kevin finally gives him a safe place to exhale for the first time in years.

It is damn near impossible not to be moved by Chiron’s quiet, slow-moving self-destruction, a process so dark and unstoppable that not even Theresa or Kevin – who at one point, becomes part of the problem and not the solution – are able to stop it.

Chiron’s is a life lived in an existential war zone and you can help but ache for him as you see him transformed from a tender, of embattled young boy and to an angry, resentful, barely-holding-it-together teenager and finally a hardened adult who’s pretty much given up on life as he once dreamed it could be.

The isolation and loss that Chiron experiences is vividly brought to life by fine performances by all three actors who play the character, most particularly Trevante Rhodes, a sparsely melodic, emotionally-resonant by soundtrack Nicholas Brittel and cinematography by James Laxton which lingers on Chiron’s face as a thousand contradictory, mostly negative emotions, flash across his face.

It’s the particular decision by Jenkins to use dialogue only when it’s absolutely necessary that accents how intense, and ultimately debilitatingly damaging, the business of growing up for Chiron, who is barely able to salvage anything of himself under the sustained attacks, both emotional and physical he sustains.

His is a life in perpetual triage, and Jenkins excels in bringing this unpalatable reality to the fore time and again, reminding us that no amount of willpower and self-survival skills, and Chiron does have them in spades; they’re simply not equal to the task at hand alas, can save someone when their very sense of self, and the security that brings, is constantly under assault.

While this may seem bleak and unyielding, there are moments of hope and inspiration throughout, particularly in the final, profoundly quiet and romantic scene when Chiron realises under Kevin’s tender ministrations that life may not be done with him yet.

You can also see Chiron relax as years of holding it all in, of pretending to be someone he’s not simply to survive, come away, if only a little at first, and he begins to see that perhaps there is a way forward that will allow him to finally and definitively be himself.

It’s all anyone who has been under constant emotional assault all their lives wants – the chance to rest, relax, put away the existential boxing gloves and simply be, and watching Chiron endure the damage but then rediscover the hope that he can still reclaim who he is, makes Moonlight one of the most powerful, important and deeply films, not just of sexuality but of humanity itself, to come along in years.