There are movies, and they are surprisingly few and far between (despite what the endless awards ceremonies may decide and confer), which says an extraordinarily moving amount about the human condition in a voice barely above a whisper.

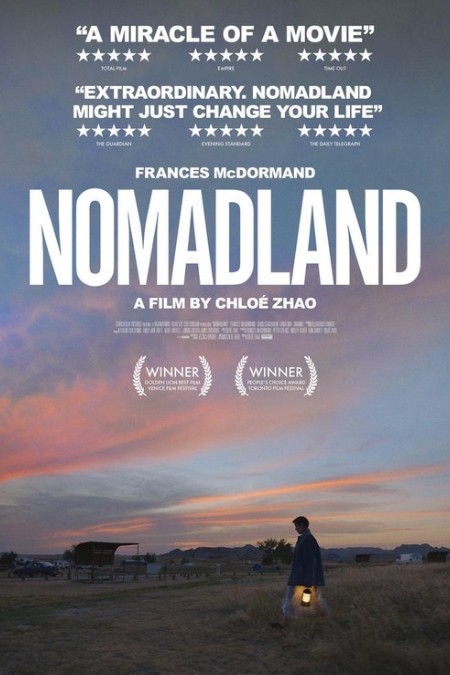

As a society, we tend to associate loud and vocal with important and worth listening to, but the truth of the matter is that there is far more worth paying attention to in a beautifully and quietly executed film like the Chloé Zhao-directed Nomadland than in a thousand of its more vociferously hard-to-miss counterparts.

Much of that richness of message and emotion comes the story itself which explores in bare bones, unflinching honesty the life of “Nomads”, people who roam the United States in their campers and vans in search of work to sustain a basic level of existence.

While for many there is an unavoidable economic necessity at play, with the next meal or fill up at the petrol station depending on finding scarce seasonal work, there is also a need to overcome past hurt or trauma, the kind that only finds true solace out on the open road in your own quiet company.

As the head of the Rubber Tramp Rendezvous, an annual gathering of people to embrace a minimalist nomadic, van-based lifestyle, Bob Wells tells the film’s protagonist Fern (Frances McDormand in luminously understated form) at one point there is a great of hurt amongst the people who drive the roads in search of whatever life still has left to offer them.

Wells is one of a host of real people who populate Nomadland to a vitally affecting degree, their stories of actual life on the road, drawn from the non-fiction book Nomadland: Surviving America in the Twenty-First Century by Jessica Bruder on which the film is based, and it is his story and those of countless others than let this superlative piece of filmmaking such a moving degree of authenticity.

There is a seamlessness to this marriage of the made-up and the real, and it isn’t until you see the credits at the end of Nomadland, that you fully comprehend how many real people brought this invigoratingly real to nuanced but eminently powerful life.

People like Swankie (Swankie), an older woman suffering from cancer, who is determined to retrace all her fond memories of youthful travel and die, not in a hospital but in the wild places such as Alaska that she loves, and Linda May (Linda) who becomes a form friend to Fern, guiding through the ins and outs of finding work, making friends amongst fellow Nomads and surviving what is an unforgiving life in a country where government and society fails far too many people for comfort.

Told in unadorned scenes that rely on an almost documentary style of filmmaking that is content to let the people tell their story with the existential power inherent in their lives, Nomadland conveys with richness just what this lifestyle means to people such as Swankie, Linda May and Fern, the one fictional member of the community whose story is nonetheless representative of what life is like for these people.

Fern is on the road because her home in Empire, Nevada, a company town in the desert created to provide residences for workers at the Gypsum plant there, was shut down, the economic rationale for its existence deemed to be no longer of relevance.

A decision made by accountants however had powerful consequences for people like Fern who loved the small town intimacy but who also valued the links it gave her to her dead husband Beau whose death led her to sell all her possessions, buy a van and to carve an existence from a place she felt very much at home.

We meet Fern once she’s on the road in a van that is artfully and cleverly packed with a small makeshift kitchen, a cosy bed and special mementoes of her life including her husband’s old handmade fishing box, now fashioned into a kitchen cupboard-cum-shelf and her father’s set of dinner plates collected over a lifetime from garage sales.

The van is Fern’s whole world, and she, like so many people, is out in the forgotten corners of America eking out a living at places like Amazon fulfillment centres, farms, parks and tourist traps, impelled to earn money to survive but also needing to find some sense of peace, however fleeting, from a life that has lately offered very little in the way of emotional comfort or physical sustenance.

The film is unstinting in its portrayal of the terrible consequences of a society that venerates capital “I” individualism and small “g” government and you are left in no doubt that the Nomads are the victims of a world that has forgotten what community and care for those less fortunate even means.

But even more powerfully in a sense, it demonstrates how people hurt economically and emotionally can find purpose in a nomadic lifestyle and family with each other and how that, in some small act of recompense, find some sense of restored meaningful humanity in lives shorn of that in many ways.

To be clear, it does not in any way romanticise a world forced on people by economic privation but it is honest about how the human spirit manages to rise up and mean challenges that on face value look to be too great to even contemplate tackling, much less surviving through.

McDormand’s performance is powerful, as is that of David Strathairn, a man she comes to know and who comes to care for her a great deal in a way that Fern may not be ready to deal with, caught up in grief as she is (though Nomadland does show her gradual journey through that in ways that are quietly, powerfully moving), and it is because of McDormand’s commitment to an authentic performances that matches the real people around her, that the story of the outsiders society has left behind, is so impactful.

Nomadland is, simply put, beautiful beyond words.

Possessed of arresting cinematography, courtesy of Joshua James Richards, and a screenplay happy to take its time, the film doesn’t pretend there is anything romantic about the deprivation and poverty and grief of the Nomads but then neither does it ignore the close bonds and friendship —- poetically meditative and emotionally powerful, Nomadland is exquisitely, movingly good, a story that celebrates the very best of resourceful and caring humanity even as it boldly and honestly depicts how society has failed people who by rights should living their very best days at the ends of hardworking, giving lives but who instead must scrabble to survive in a world that seems to have forgotten them.