There is an exquisitely poignant beauty throughout Tigertail, Alan Yang’s masterfully-realised tale of regret and loss and possible new beginnings, that gives expression, both visually and verbally to the pain we all feel at life’s profound might-have-beens.

It is a slow-building pain, one that doesn’t begin to really make its presence felt until we are well-advanced in years and any chance we have of rectifying past errors or making up for past losses has receded with the unforgiving passage of time.

When we are younger, of course, life feels limitless with possibilities, an undiscovered country of what-ifs that stretch far beyond the limited vision we are afforded at the time.

Youth affords us many things – get-up-and-go, passion, a seemingly inexhaustible appetite for new ideas and ways of doing things and an indefatigable optimism that everything will work out somehow.

What it doesn’t give us, always, however, is unlimited options something that Pin-jui (Lee Hong-chi and then Tzi Ma), a poor young man from the Taiwanese countryside knows all too well.

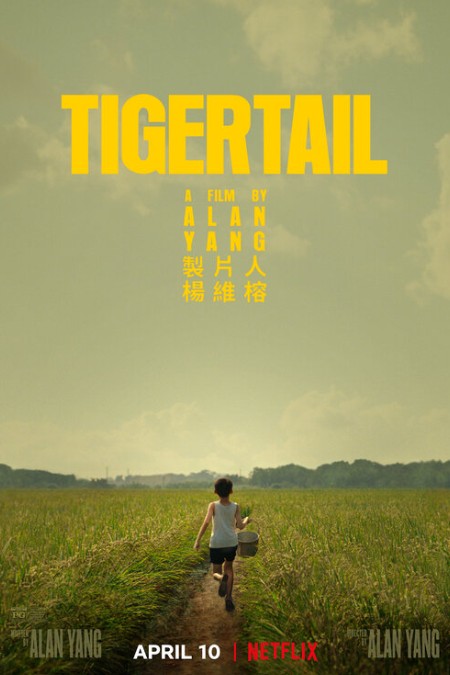

Forced to live with his grandparents at their rice farm just after the Kuomintang have fled to Taiwan, and then with his single mother Minghua (Yang Kuei-mei) at Huwei (Tigertail which is where the film derives its title) where they both work low level jobs at a factory, Pin-jui dreams big of moving to America and making the money which will give him and his mother the independence and choices he wants for them both.

He has the hopes and dreams nailed down tight, but his options are few, the only viable one being to marry the factory owner’s daughter Zhenzhen (Fiona Fu then Kunjue Li) and with his new wife’s father’s backing, forge the hoped-for better life in the land of the free and the home of the brave.

The great, almost-certain-to-induce-lifelong-regrets snag to all this promise and possibility?

Pin-jui is in love, the head over heels kind from which there is no return for the rest of your natural life, with Yuan (Yo-Hsing Fang then Joan Chen), the daughter of a wealthy family whom he met as a child in his grandparents’ rice fields and with whom he has passionately reconnected as an adult.

He doesn’t want to leave or abandon her but deep down he knows that her family will never accept him and that the only hope he has of making a life for himself and his mother, whom he adores and with whom he is very close, is to marry Zhenzhen and see if his dream, his youthful, vibrant dream has legs.

Moving back and forth between his youth and the present day where his stern grandmother’s advice not to talk so much and not to cry has left him emotionally isolated from his daughter Angela (Christine Ko) and divorced from Zhenzhen, a man who is “broken inside” according to someone who should be close to him but who is not.

It’s hardly the fulfilment of his youthful fantasies and his response to all this loss, compounded by the recent death of his beloved mother, is to shut down still further, receding further and further from the hopeful, vibrnat young man he once was and with whom Yuan fell deeply in love.

That may sounds so desperately sad that you may wonder if you will ever smile again after watching Tigertail but so expertly and insightfully does Yang (Master of None, The Good Place) tell the story of Pin-jui, modelled on his own family’s own immigrant experience into the United States, that what drives you instead is a profound appreciation for the way life may defy our ideas of what it will be but how, if we are open and willing, that that is not necessarily the end of the road.

There is an aching sadness to much of Tigertail, which finds an outlet in cinematography so beautifully moving that you will sigh at the sheer resonance of it, but there is also great love, nascent re-connection and a sense of growing hope that what has been lost, while it may not be found or made up for in any meaningful way, may yet give rise to something equally as satisfying.

Yang, who both wrote and direct the film, which fits snugly into its 90-minute running time, wasting not a second of any scene so elegantly well is it told, has crafted a tale which is brutally honest about life and its ups and downs (both those beyond our control and those whose outcome rests fully at our feet) but also curiously, quietly hopeful that redemption of some kind is possible.

It doesn’t shout this from the rooftops; it actually doesn’t shout anything from the rooftops thankfully, happy to let its story unfold in the kind of meditative way that immerses you deeply and profoundly in Pin-jui’s life over many decades of dreams realised and hopes foregone.

Matching this rewardingly introspective tone is breathtakingly moving, and arrestingly eye-catching cinematography from Nigel Bluck who uses a recurring motif to communicate how close together Pin-jui and first Zhenzhen and then daughter Angela are geographically and how far apart they are in every other respect.

In various scenes, we witness Pin-jui and Angela eating meals alone as the scene cuts back and forth between their respective tables so that it looks like they are together when they are in fact far part; similarly when both are walking down the streets close to their homes, you expect them to get to meet so similar do their trajectories appear but of course they never do.

Every single one of these montages are thoughtfully executed, things of affecting beauty that tear your heart out in desperately sad pieces while piecing it back together as they hold out the tantalising possibility that the sad and sorry mess that is Pin-jui’s twilight years may yet find purpose, closeness and emotionally meaning for him and those still in his orbit.

Tigertail is a masterfully-made and told film – thoughtful, contemplative, and poetically poignant, every mesmering scene matching the rich and affecting emotions of a slowly-unfurling story that says a great deal in an immersively understated way, leaving us all too aware of the great price of past decisions but hopeful too that something can be salvaged form the consequential mess of regret and loss, something that might be very good and life-transformingly wonderful indeed.