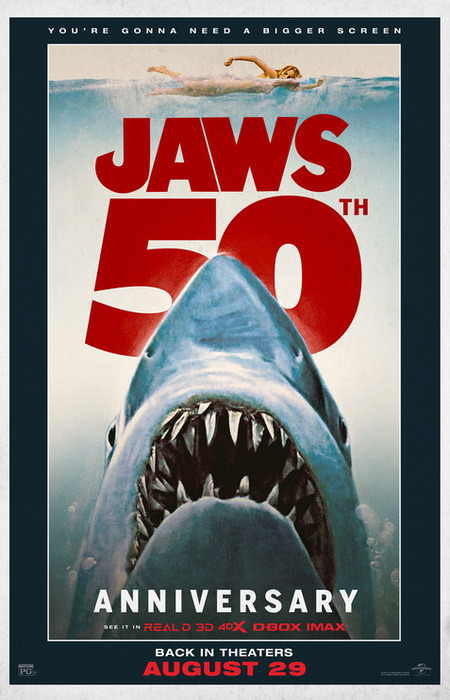

(courtesy IMP Awards)

It’s well recognised time memories are a wholly unreliable witness.

We might think we are recalling things exactly as they are, but when the truth of the matter surfaces, it soon becomes clear that we remember is not the whole truth and nothing but the truth but a garbled jumble of thoughts and moments that together do not add up to the original whole.

Case very much in point is the 50th anniversary of Steven Spielberg’s zeitgeist bursting second film Jaws, based on the book by Peter Benchley, which at the time of its release, gave people more than a little pause about ever venturing into the ocean again.

If you had asked this reviewer what they remembered about the one of the first great blockbuster films of the modern cinematic era, they would have cited that chilling first death of a lone woman swimmer who made the big mistake of going for a dip at night or the terrifying rush of panicked beachgoers from the surf when a giant shark, previously scorned as the figment of police chief Martin Brody (Roy Schneider) and marine biologist Matt Hooper’s (Richard Dreyfuss) fevered fears and imaginations, snatches a young boy off a li-lo (inflatable surf mat) and makes a bloodied meal of him.

Those moments are justifiably scary and memorable and it makes sense that they’d lodge in the memory and that you would access them as the sole narrative substance of Jaws; after all, it’s just a film about shark attacks, right?

Ah well, that’s where our memories tend to let us down, especially when it comes to the new bright and shiny 4k-restored version of Jaws which sparkles with renewed visual vigour and vim.

It turns out, 40 or so years after last seeing the film – Jaws, like many blockbusters, was a staple of many free-to-air TV networks in the pre-cable and streaming era when movies were a solid anchor for a whole-of-family viewing nights – that there’s a great deal that our memories left behind on the nostalgia-cluttered cutting room floor.

For a start, this is a film that has a lot more ruminative moments than you remember, and which, for all its highly-adrenalised, high octane scenes, takes its time to tell the story of many of its central characters.

Its narrative patience means that it has a lot more characterisation than it’s generally credited for.

Sheriff Martin Brody, played with a real vulnerable and highly accessible humanity by Schneider, is the Every Person of the piece, a family man who panics as easily as the rest of us, his fires of concern for his wife and family, expressed in ways that sit in stark contrast to his expectedly sage role as the fine word in law enforcement on small Amity Island, which depends heavily on summer tourism to stay afloat.

He is caught between his duty as a law man and his role as a loving dad and the pressures placed on him by Mayor Larry Vaughn (Murray Hamilton) and his myopic council who refuse to see the facts on the ground, or swimming menacingly underwater, because it conflicts with the version of events they want to be true, and while Jaws doesn’t overly ruminate on what it’s like to be crushed between the two, it affords the sheriff more time than you’d expect to be a real human being and not simply a one-note character caught between competing interests.

While not as much time and effort is given to the other central characters like the mayor, Matt Hooper and wizened shark hunter Quint (Robert Shaw), they nonetheless get far more fulsomeness of character than your memory might suggest, with Spielberg’e focus on characterisation lending the film far more emotional heft than you might otherwise expect.

Granted, we’re not talking Oscar-winning levels of characterisation here but there’s far more at work than just shark attack – panic and scream – shark attack – panic and scream, and rinse and repeat, and it helps you to appreciate why Jaws has lasted the distance and still attracts crowds at cinemas now on its rare outings.

Having said that, Jaws is still very much a blockbuster.

It lives to keep us on our toes, and scare us when it needs to, and it does that terrifyingly well, especially when the giant shark villain of the piece, a robotic construction that Spielberg reveals in an intro to the 50th anniversary screening that was known as “Bruce”, comes lurching onto Quint’s beleaguered shark hunting boat or when Brody and Hooper find a wrecked fishing boat with an unexpected wormy inhabitant who appears just when you’re worried about something else entirely.

The thing is that even the more obvious elements of the film such as rightness vs. power and the shark attacks and ensuing panic themselves are done really well, gaining real emotional power and impact from the fact that they are buttressed by scenes of people behaving, albeit with a heightened degree of hyperbole, much as you’d expect them to.

The shark attacks more than still stick their landings but they come across as even more intense than you remember them when you’re reminded about how what leads into them and what follows them.

Jaws exists to thrill and excite, yes, but that impacts you even more when you are given a memory prompt about how peoples’s foibles, fears and flaws become almost as much of a threat and an issue as the shark itself.

Watching Jaws 50 years after it release, and for the first time in the cinema for this reviewer whose parents likely wisely decides not to traumatise their ten-year-old who spend summer holidays swimming at the beach with his beloved grandfather, is a revelation because while it is, in parts, exactly as you remember it, it’s also a million light years from what your memories recall, serving up a thrilling, edge-of-your-seat story of death and loss and horror while bolstering it with a real emotional thoughtfulness and a rich characterisation that gives it far more lasting heft than you might otherwise recall.