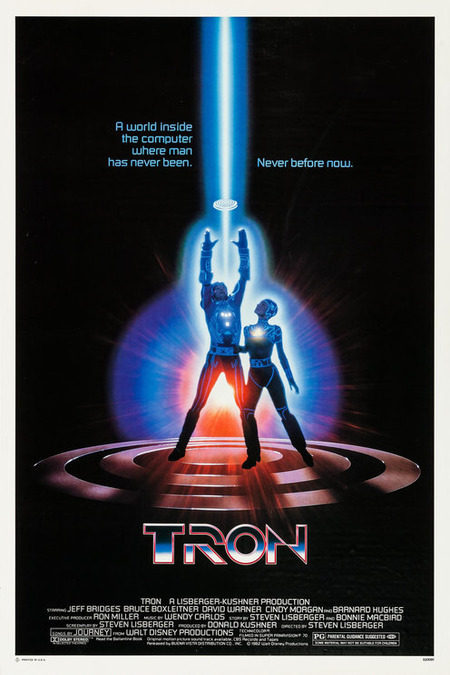

(courtesy IMP Awards)

Jumping back in time, if not literally then at least cinematically, is always an interesting exercise.

Nostalgia exerts a powerful pull on all of us, and watching how it fares when it comes to seeing the object of its hagiographying live and in person again is a fascinating thing to undertake – either we remember the movie, in this case at least, exactly as it is, or we have wrapped so many layers of fond recall around it that the actual experience cannot even begin to compete.

When first this reviewer hit “play” on Tron, there was a sense that nostalgia had won and the movie itself was coming off as a poor second cousin, encumbered by barely embryonic CGI – Tron was one of the first films to use it – and an aesthetic that looked very early 1960s Doctor Who.

But then something rather unique happens; you ditch any unspoken demands that Tron look as dazzlingly good as the film you saw last week at the cinema – it can’t of course though Tron: Ares, its second sequel, now in theatres, does make comparisons, however unfair, all but impossible – and settle into how cleverly the makers of the 1982 film bring the inside of the digital world we now take for granted well and truly alive in all its horrific glory.

The story is the thing here, putting forward the idea that the programs that run our lives, and which were in their infancy back in the early ’80s when desktops were a pipedream and the online world barely affected anyone, are real, living creatures of brightly-lit, energised 0s and 1s who wants freedom as much as anyone.

Leaving aside the fact that these programs are products of their “users” as they’re termed, and really only have limited agency anyway, what Tron rather brilliantly argues is that everyone, flesh and digital alike, wants and needs is the right to be who they were made to be.

When programmer Kevin Flynn (Jeff Bridges), who has had his key role in digital wares company Encom usurped by the villainous Ed Dillinger (David Warner) and his video gaming IP stolen – much of which finds its way into the marvellous world-building of life inside the computer – is sucked into the digital world he has helped create, he finds that it is utterly under the thumb of the evil, ever-growing entity known as the Master Control Program (the MCP).

Amassing programs from right across the digital landscape, including actuarial programs like Ram (Dan Shor) and key Flynn ally as the story progresses, the titular Tron (Bruce Boxleitner), the MCP aims to subvert the world to his power hungry whims, arrogantly consumed by the idea, like all god-like AI before and after him, that he is better and knows better than his creators.

In his pursuit of power, absolute power, he has created an authoritarian hellscape inside the world’s computers where programs live and die at he ordains and where, Borg-like, he absorbs programs to bolster his own programming, assuring the hapless entities, who do agency and a sense of personality, that they will be better off within him than standing on their own energy-pulsing feet.

It’s here that Tron becomes a very clever movie indeed.

Because while it might look like it is primarily a video game sprung to internally brightly-lit life, and that is definitely an element so if, like me, that’s what you remembered as the core of the film your nostalgia isn’t completely off the mark, it is also an impressive exploration of what happens when power becomes concentrated in the hands of one person who cannot help but be corrupted by it as the axiom by Lord Acton makes frighteningly clear.

Given we created the world of Tron, the fact that this axiom applies to bits of light and data as much as it is does in the outside flesh-and-blood world shouldn’t come as any surprise, and the film makes a great deal of the efforts by Tron and Ram, and others like Yori (Cindy Morgan) and Dumont (Barnard Hughes) – pretty much all the characters who inhabit the digital world have “user” counterparts on the outside so all the actors double-dip to good effect – to fight for a freedom the MCP has increasingly sought to deny them.

It is not a spoiler alert at all, because this is a Disney film, to say that they succeed, but what is also incredibly fascinating about Tron, directed by Steven Lisberger to his own screenplay in turn inspired by story ideas he co-dreamt up with Bonnie MacBird, is the way it shows how authoritarian regimes do their best not only to strip people of their agency of action but of belief too.

In the digital world, there is a strong and recurrent digital belief that somewhere out there are “users”, people who direct and inspire their programs and who give them meaning, purpose and value.

It’s essentially a religion of comfort and reassurance, most heavily drawn upon by the programs under threat from the MCP, and its exactly the sort of thinking and motivational belief that his evil regime seeks to stamp out lest it give them hope they can supplant the dictatorship that literally controls their digital life and death.

Tron, as a result, is a highly intelligent, emotionally and culturally savvy film that is ostensibly about digital forces for insidious control and liberating freedom fighting it out in what are still pretty cool visuals to watch, but which also goes deep and hard on what it means to be free and what that gives you and why you should never surrender yourself to more powerful forces.

All Flynn may want to do is get back to the “real world”, and yes, of course he does, but as he does so, he sets in train a glorious revolution and gifts us with a film that is way more dense and clever than you will remember and which well and truly deserves further exploration in the sequels that have followed.