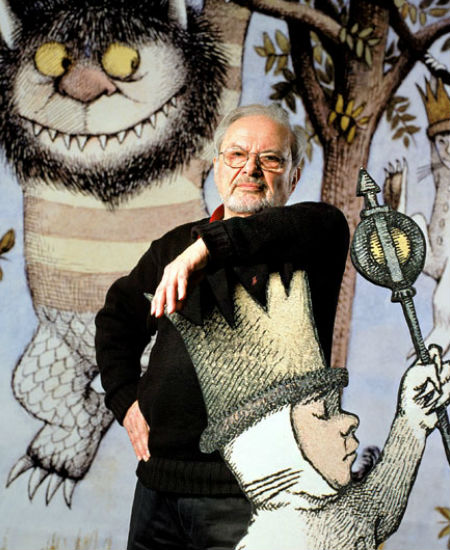

Maurice Sendak, much loved and admired author of the children’s classic, Where the Wild Things Are, and In the Night Kitchen, among more than 50 books he wrote and/or illustrated, died Tuesday US time of complications from a recent stroke.

“I don’t write for children. I write…”

While he was primarily known for these seminal works of children’s literature, which evinced his love of disobedience and his childhood experiences of fear and social isolation, he did not see himself as a children’s author. In an interview with Stephen Colbert just a few months ago, he had this to say about people pigeonholing him in this way:

“I don’t write for children. … I write. And somebody says, ‘That’s for children.’ I didn’t set out to make children happy. Or make life better for them, or easier for them.”

He took pride in the fact that he didn’t sugarcoat childhood, believing that children are more in touch with the unsettling realities of life than adults give them credit for.

“From their earliest years children live on familiar terms with disrupting emotions — fear and anxiety are an intrinsic part of their everyday lives, they continually cope with frustrations as best they can. And it is through fantasy that children achieve catharsis. It is the best means they have for taming wild things.”

[upon winning the Caldecott Medal in 1964 for “Where the Wild Things Are“]

He had this to add on the subject when he was interviewed by Sarah Lydell of The New York Times in 1993:

“Grown-ups desperately need to feel safe, and then they project onto the kids. But what none of us seem to realize is how smart kids are. They don’t like what we write for them, what we dish up for them, because it’s vapid, so they’ll go for the hard words, they’ll go for the hard concepts, they’ll go for the stuff where they can learn something, not didactic things, but passionate things.”

Real children

His creations in short behaved like real children. They happily ventured fearlessly into the frightening world around them, challenged authority and worked things out in ways only a child could.

This realistic portrayal of children was in stark contrast to much of the children’s literature that existed before Maurice Sendak began writing books in the 1950s. Unlike the more compliant children in books like the Dick and Jane series, the children in his books challenged conventional notions of how children should behave, or react to certain situations, and Sendak made no apologies for this though it earned him opprobrium from certain quarters.

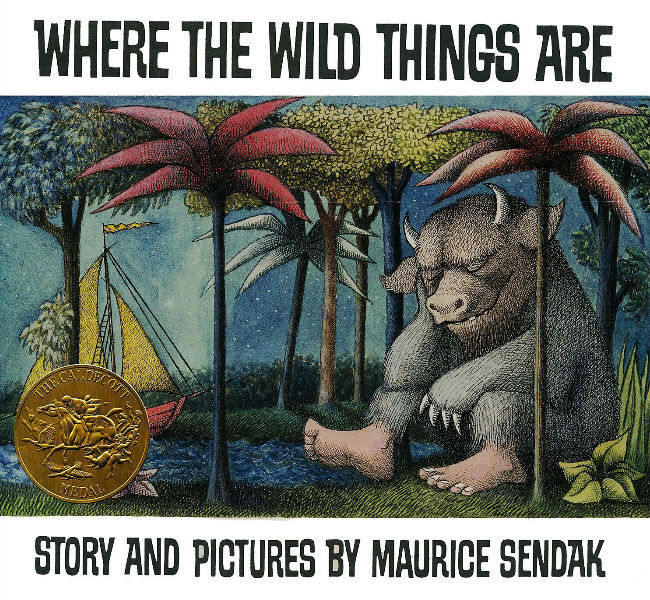

The most famous example of his “unorthodox” children was Max, the protagonist in the book that made Sendak a household name, Where the Wild Things Are (which became a hit movie in 2009). After misbehaving, Max is sent to his room as punishment without dinner. But he is not repentant and defiantly remains in the room. It is only after he is transported by boat to an imaginary jungle land populated by monsters where he confronts the things that fear him that he returns to the real world of his bedroom where he finds supper waiting for him, piping hot.

The best fans are honest ones

Despite his curmudgeonly image, Sendak, who admitted he was glad he had never had children, loved hearing from children and celebrated their honesty even when it wasn’t particularly flattering of him. In an interview with Joe Fassler of The Atlantic Magazine in 2011, he said:

“Well, when a kid writes to me—as a kid did write to me—and says: ‘I hate your book. I hope you die soon. Cordially.’ Well, the combination of ‘I hope you die soon’ and cordially’ is wonderful. It shows how bewildering the whole thing was to her—and to me.

She was allowing herself to hate. ‘I hate your book.’ But she’d learned in school that you’re supposed to end your letter with the words ‘cordially’ or ‘best wishes’. And so they combine both without thinking there’s something goofy in such a thing. But that’s their charm, and that’s what we lose by growing up—lose, lose, lose. And if we’re lucky, it happens again when we’re old. And I’d like to believe that it is happening to me. Things that were so wonderful to me come back now. And I’m so grateful—because I wouldn’t know how to start otherwise. But it’s happening.”

But it wasn’t just his own books that Sendak was known for. He was also a much in demand illustrator who worked on projects as diverse as Else Holmelund Minarik’s book series, Little Bear (which he later helped turn into a TV series), and George MacDonald’s The Light Princess. He also loved creating costumes for ballets and stage operas, designed sets for the New York City Opera and even wrote a libretto for Oliver Knussen’s opera adaptation of Where the Wild Things Are, which had its premiere as Max et les Maximontres in Brussels in 1980. [source: Associated Press]

Sendak, born in 1928 to Polish immigrants in Brooklyn, kept creatively busy to the end, releasing his most recent book, Bumble-Ardy about naughty pigs having a party, in 2011. He freely admitted that work had been his sole reason to keep going in recent years and that though he was appreciative of the life he had led, that he missed those who had died before him (including his partner of 50 years, Eugene Glynn):

“I want to be alone and work until the day my head hits the drawing table and I’m dead. Kaput,” he said in autumn of 2011. “Everything is over. Everything that I called living is over. I’m very, very much alone. I don’t believe in heaven or hell or any of those things. I feel very much like I want to be with my brother and sister again. They’re nowhere. I know they’re nowhere and they don’t exist, but if nowhere means that’s where they are, that’s where I want to be.”

Wherever it is that Maurice Sendak is we hope that those he is with are as entranced by his trademark wit, honesty and love of words as we were during the time we were privileged to have him among us.