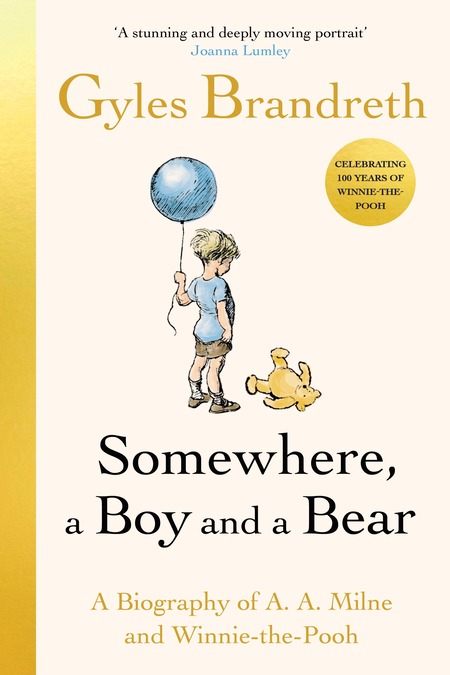

(courtesy Penguin Books Australia)

Childhood is in many ways, the most perfect and yet, once departed, the most impossible of idylls to return to, and yet as the enduring power of A. A. Milne’s now 100-year-old creation Winnie the Pooh reminds us in ways melancholic and yet comforting, it doesn’t stop us from trying to recapture its fleeting wonder.

In his exquisitely intimate biography of both the author and his “bear of very little brain”, Somewhere, a Boy and a Bear, Gyles Brandreth ostensibly takes us deep behind the scenes of Milne, his wider family and the ways in which the dynamics of this divided familial group affected each and every member over successive generations, but beyond that, what he beautifully does is explore how potent a thing innocence and childhood is and why we cling to it so fiercely.

Our enduring need for the comfort of stories like Winnie the Pooh, quite simply one of the greatest characters ever created in any form of literature speaks to how dark and troubling the world can be, and that we often find little solace in the adult world that we have no choice to grow into, lamenting as we do that we cannot recapture what it meant to be a child and simply be happy and be (assuming that is our lot of course; it’s not always the case).

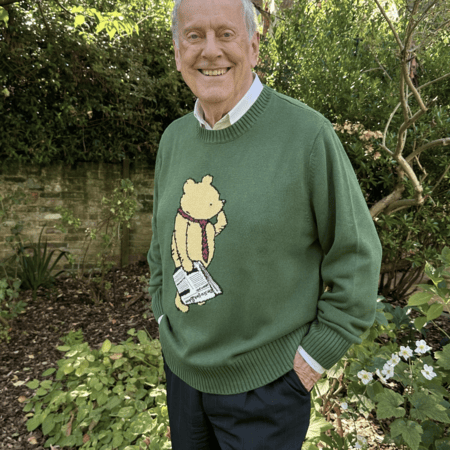

Drawing on his friendship with Christopher Robin himself, which came about in the 1980s when he was writing a play on A. A. Milne’s life, Now We Are Sixty (a play on Now We Are Six, Milne’s 1927 book of delightfully whimsical children’s poetry), Brandreth takes us on an exceptionally illuminating exploration of the life of Pooh’s creator and how and why the bear’s appeal has been sustained for 100 years.

This is a book about a boy and a bear, but it is also a book about fathers and sons, about the effects of parents on their children, about the nature of childhood itself – about the magic and the mystery and the importance of childhood.

Winnie the Pooh, so named because “Winnie” was the name of Christopher Robin’s favourite black bear at London Zoo and “Pooh” was a fun name the Milne family gave a swan one year on holiday – Christopher Robin didn’t hesitate to bring the two names together to name his Harrods-bought teddy bear – first came to public notice on Christmas Eve in 1925 in London’s Evening News.

This story, specially commissioned by the paper, led to two books – Winnie-the-Pooh (1926), and The House at Pooh Corner (1928) – and followed Pooh being featured, though not exactly as he came to be known just a year later, in a poem When We Were Very Young (1924) with appearances in a great many more poems in Now We Are Six.

Such was Pooh’s almost instant popularity, which shows no sign of declining even a century later, that Milne’s career as a much-lauded, highly successful playwright on both sides of the Atlantic, and his decades-long success as a writer for the UK’s legendary Punch magazine (which ceases publication in 2002) and a range of other illustrious magazines and newspapers, came to be eclipsed by a bear, a pig, a tiger and a number of other characters which the world took to their hearts.

(courtesy official Gyles Brandreth Instagram)

While readers of the four books featuring Winnie the Pooh would likely see no possible downside to being feted as the author of such a beloved character, Milne saw plenty.

Setting out to be a serious writer in face of family pressures to enter into the teaching profession – his father was a teacher all his life and the founder of two schools, one of which was highly regarded in its time for the quality of its education and the empathy of its staff – Milne was not the kind of man who wanted to be known for just one thing.

He saw himself as a serious writer, even if ironically much if his theatrical and magazine/newspaper was of the humourously satirical kind, and the idea of being pigeonholed as a children’s writer did not sit well with a man who, Brandreth points out many times in Somewhere, a Boy and a Bear, refused to ever do what the world expected of him.

So, while others may have caved and written more of what the public wanted, albeit with some reluctance, like the creator of Sherlock Holmes, Conan Doyle, Milne steadfastly refused, even going so far to offer up more children’s verse in 1927, wonderful though it was, when what his published actually wanted was a sequel to Winnie the Pooh and fast to capitalise on its rapid, meteoric success.

You could chalk this to an author laudably sticking to his guns and being true to himself, and in the meticulous but highly readable charting of Milne’s life in Somewhere, a Boy and a Bear, there’s a good case to be made for this, it also smacks of a man wilfully refusing to do anything that would compromise his unflinching artistic vision and his commitment to a career he zealously tended.

The characters Milne created are immediately recognizable. There is only one human being in the stories, Christopher Robin, but, somehow, all human life is there. The stories themselves are funny and exciting, full of surprises and nonsense, with moments of sadness, moments of joy, moments of danger, moments of delight. There is wit; there is wordplay; there is wisdow, too. The philosophy of Pooh is profound. (page 365)

Somewhere, a Boy and a Bear does an empathetic job of taking us into Milne’s life and explaining how a man who wasn’t close to his father and mother, devoted though they were to him, who hated one brother and adored another, and who lost closeness to his son as time went on, their relationship schismed by a perceived use, by the son, of his personhood to sell the Pooh books, still managed to touch the heart of millions.

The genius of this charmingly incisive portrait of one man and his cuddly creation is that Brandreth lays bare Milne’s life but not as an act of crucifixion or excoriation but rather as a way of explaining how Pooh came to be and why, expansive though his influence is, his life is largely confined, Disney’s canon aside, his literary life was confined, however wonderfully to just four books.

But what Somewhere, a Boy and a Bear, which is intimate and moving and just beautiful, really is is a deep dive into childhood and why it matters and how our departure from it never sits still and how it drove one man to create a bear who continues to take us back to this wondrous time over and over again and who will likely do so for some time to come.