Whether we know it or not, we are powerfully shaped by our stories and histories, by where we belong and who we belong to, and by how the past is inextricably part of our present.

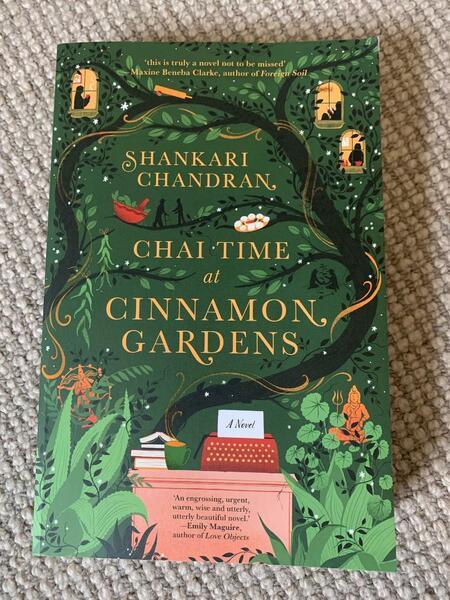

This truth is captured with powerfully moving resonance by debut novelist Shankari Chandran who writes in Chai Time at Cinnamon Gardens with profound truthfulness and honesty about the how the experiences that mould us, for good and for bad, are never really left behind.

There is no academic undertaking for the characters in this luminously resonant novel which grapples with some truly confronting issues and hard, bloody truths, the kind that many of the people who live or work in the communal delights of Cinnamon Gardens Nursing Home would like to leave to leave behind but which are never really far from who and where they are now.

But the novel also talks about how, even in the wake of pain and trauma, that we can find new bonds, new companionship and comfort, something that is bountifully present in the home which works hard to make the mostly Sri Lankan-Australian residents feels as if they have found somewhere they truly belong.

The owner of the home is Maya, a Hindu Sri Lankan in her 80s who is herself now a resident, in the #1 room in the front part of the nursing home which occupies a beautiful Federation building which she, her Muslim husband Zakhir, who struggles with a torturous past wrought in the bloody violence of the Sri Lankan civil war, and their old friend Cedric have restored, even as they built another more modern building behind it.

“And so Maya, Zakhir and the twins moved into the caretaker’s cottage, fifty metres from the nursing home at the bottom of the property’s wild garden. They had to cut a wider path through the shoulder-high weeds when Maya’s three trunks of books finally arrived by sea, months later. The name of the cottage suited her. She was a caretaker now.” (P. 13)

Maya, a writer who is keeping a significantly big secret of her own, one impelled in its current form by the implicit racism that sits at the heart of much of Australian discourse despite the country’s reputation as multicultural bastion, has worked to create to create a warm and welcoming place where everyone feels they belong.

She is helped in this later on by her daughter Anjali (Anji) who runs the home, and who, with her psychologist husband Nathan, who has taken to Sri Lankan with an alacrity that speaks to the open and supportive nature of the man, has found a place in Australian society, in the hearts of the residents and in the new world her family has created.

Her life is by no means idyllic with issues mounting from the breakup of her best friend Nikki’s marriage to local councillor Gareth – Nikki works as the medical professional on call at the home which is located the fictional Sydney suburb of Westgrove – and a growing threat to the home itself and those who live and work there from malignant societal forces but she is one of the people in Chai Time at Cinnamon Gardens who has found a home in Australia, one free from the sort of violence that wreaked havoc in her parents’ homeland, forcing them to flee in the early ’80s.

Or so she, and a great many others hoped.

The truth is, no one is ever free from past pain or present threats, and much of Chai Time at Cinnamon Gardens is devoted to exploring what happens when the past and the present collide, and untold or hidden stories are forced to come into the light of day.

While there is a great deal in this thoughtfully written novel that is confronting and even shocking – Chandran does not stint on describing the full horrors of the civil war in Sri Lanka which laid waste to precious citadels of knowledge, peoples’ lives and a sense of surety, safety and community – and will leave you gasping at the cruel length and breath of peoples’ inhumanity to their fellow citizens, the overwhelming focus in on the empowering sense of self and belonging that comes from community.

It does this in part by showing what happens when this precious sense of community is brought under threat, with a slowly building grouping of far right forces and populists taking advantage of a terrible error of judgement by one key character in the book.

It is wonderfully evident from the beautifully evocative way in which Chandran describes Cinnamon Gardens with its carefully curated menu and its expansive raft of social and cultural activities, and the close bonds that exist between the residents who, even if they always get on with each other, have found a sanctuary and found family of sorts far from the chaotic turbulence of their homeland.

“It was his turn to cry. Silent tears that found the small canyons and crevices of his ageing skin and made their way slowly to the edge of his jaw. She watched them fall to the table, sit in the dust and then sink into the wood. A small portion of this man captured by the table. Were Appa’s tears preserved in this table too?

‘Mahal,’ Uncle Mozammel repeated.

She lifted her eyes reluctantly.

‘It’s time. Ceylon will only get worse for the Tamils. Pack up your family and go somewhere–anywhere. You must get out before it’s too late.'” (P. 193)

And so when this imperfect but lovingly crafted idyll is threatened, it illuminates even more how important community is and how while there are toxic forces who seek only to destroy and not build up, it is the very strength, vivacity and tenacious buoyancy of this community that will see everyone through.

Does that mean it all be easy?

Of course not, and Chandran is wise and savvy enough to know that having a strong community is not a silver bullet to cure all of society’s ills, if only it were, but it does provide a bulwark against hatred and bigotry which as Chai Time at Cinnamon Gardens makes painfully clear, can be violently, horrifically brutal and sadly never really go away despite the sage lessons of the past.

There is much about Chai Time at Cinnamon Gardens that will shock those of us who have never had to fight for our selves, families or entire way of life, and who even in the seeming idyll of Australian society do not feel the dead hand of racism on us, but that in itself is an impelling reason to read this magnificently woven tale.

At its heart though, and it’s a vibrant and beautifully nurturing one, Chai Time at Cinnamon Gardens is a novel concerned with the universality of human experience, that all of us want to feel valued, loved, that we belong and we are safe, and that when that is interrupted or broken, we need to be able to find somewhere safe to belong again, a desperately important thing that doesn’t preclude the pain and secrets of the past from intruding but which means is often the difference between moving forward or being trapped in the moribund memories of what went before.