All of us, somewhere deep down or agonisingly close to the surface, long for a place or a person to call home.

It seems to be (understandably) hardwired into us, an impelling desire to not simply find someone or some place, because anyone can do that with enough bars, datings apps and a half-decent GPS, but to feel at ease with them, to feel like they know you and have your back, no matter what.

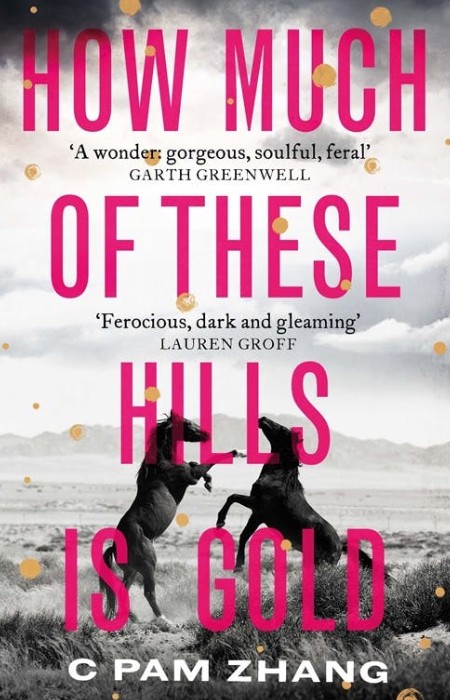

Set at the heyday of the American West, which prefers its mythos big and successfully expansive rather than corrupted and broken, C Pam Zhang’s How Much of These Hills is Gold takes this in-born need to truly, fundamentally connect and runs with it, across landscapes afflicted by drought, flood, death, fractured dreams, lost hope and a sense that somewhere out there must be a place to call home.

It is certainly what drives 12-year-old Lucy and her younger 11-year-old sister Sam, who prefers to deport herself as a boy and then later a man, comfortable in that non-binary space but also aware she has more chances to succeed if she is one gender rather than the other, as they set out to find a place to bury their troubled, oft-drunken father.

Broken by the loss of his wife and his daughters’ mother, he had struggled to evoke any sense of warmth and belonging, weighed down by his continual inability to make good on the glittering prospect of the then-evolving American Dream, a consequence both of self-sabotage but also being the head of a Chinese family in a West, geared then as now, for white people to make a go of it.

Closer to her mother (Ma) than her father (Ba), and fiercely intelligent, Lucy never really forges a meaningful bond with her father while furiously intense Sam sets out to do nothing but, eschewing school for going prospecting and mining with her father, aiding and abetting his neverending dream to get enough gold to buy that house, those clothes, the steady supply of food.

“What could almost make a girl laugh is how Ba came to these hills to be a prospector. Like thousands of others he thought the yellow grass of this land, its coin-bright gleam in the sun, promised even brighter rewards. But none of those who came to dig the West reckoned on the land’s parched thirst, on how it drank their sweat and strength. None of them reckoned on its stinginess. Most came too late, The riches had been dug up, dried out. The streams bore no gold.” (P. 10)

His is a life of dreams denied or stolen, and while Sam is determined to help him make good on his pie-in-the-sky wishing, Lucy is far more circumspect, deeply self and life aware, a young girl with her emotions close to the surface who nonetheless seems to be intuitively aware of what life is really like and what it will take to make things work.

Even so, because the characters in How Much of These Hills is Gold are real and flawed just like anyone else, this awareness, beset mostly by twists and turns that not even Lucy can counteract, she is often unable to make good on her dreams to forge something new and different from the ruined ashes of her family.

Part of the reason for her drift later in the book is her lack of any real sense of connection to Sam; it’s there in some form, buried deep down, but neither sister can seem to find it, a lost sense of togetherness that both of them need if they are going to make anything decent of life.

The gold in the title then is not simply actual gold itself, which is a recurring motif in the book standing for actual material wealth as much as the fulfilment of sparkling possibility, something the West promises but doesn’t always deliver on, but the search that the girls embark when the flee their home to bury their dad, a search that involves a frantic reaching for sibling connection as much as anything else.

Writing with luxuriously luminous prose that is beautiful in and of itself even as it brings forth emotions and insights that will leave you gasping with their honesty and truth, Zhang infuses How Much of These Hills is Gold with a desperate sense of life and family longer for and never found.

If this sounds depressing, it is anything but from a writer who understands the paucity of result that accompanies once-vibrant hopes and dreams is not always the end of things.

For Lucy and Sam it often feels like that, as they take one foot forward only to be pushed a thousand by a world that won’t play by the mythological rule book of the American West.

But it’s often not so much what happens to the girls, and to the family as a whole as their journey to the present is told in poignantly-affecting, sobering flashback, but what they feel and see that really knocks you sideways.

As they journey out to bury their father, and it becomes obvious to Lucy that Sam’s restlessness precludes any possibility they will both find a burial spot and an eventual home, you ache for them to discover that their greatest richness lies in the loose and unravelled bonds between them.

If that sounds twee or like something out of nascent Disney film narrative, it is absolutely anything but; what the sisters have is real and true but it’s obscured by the pain of their parents, their upbringing and by a world which sees no value in their Chinese identity, despite it being very much expressed in their innate Americanness.

“And so Lucy soaks in the river, alone as she was before. Her skin puckers into damp ridges. Still she floats. Imagining a future in which she is as wrinkled on land as she is in water, and still sitting, smiling beside her friend. What other future can there be? She’s become what she said: Orphan. No one. No fortune, no land, no horse, no family, no past, no home, no future.” (P. 205)

Sadly, Lucy and Sam are all too aware that their ethnicity trumps their status as American-born citizens in the eyes of too many people, who don’t see them as valid additions to a very whitewashed American Dream.

In their own ways, the two sisters fight back against this entrenched racism, but they are hobbled by human frailties and being the product of two people who tried to fight the same fight only to have their dreams flung cruelly back in their faces time and again.

How Much of These Hills is Gold is such an all-consuming, endlessly immersive and heartrendingly affecting read because it tells its big story against the flaws and intimacies of raw humanity, the kind that wants more than it has got in the very best and necessary of ways, that wants material success but more so, wants abiding and fulfilling connection and love, a place to call home that feels like somewhere they can belong now and forever, and which comes what may won’t ever let them go again.

Lucy and Sam spend the entire beguiling story searching for this in ways vastly different from each other but with the same intent – to find each other, find a home together and to realise the fulfillment of possibility that once eluded their parents but which they have to believe will be theirs in a way that will make all the pain and searching worthwhile.