Humanity, it must be said, loves a bit of personal PR.

It’s not necessarily a deliberate thing; we don’t step out the door each day, or in these COVID-blighted times, appear on a Zoom call, with the deliberate intention of making ourselves look as good as possible.

But our inadvertent default seems to be to project the very best of who think we are, how we want our lives to be and the shiniest, prettiest version of the world around us to anyone who might come across our path (and not just to others but quite often to ourselves, as well).

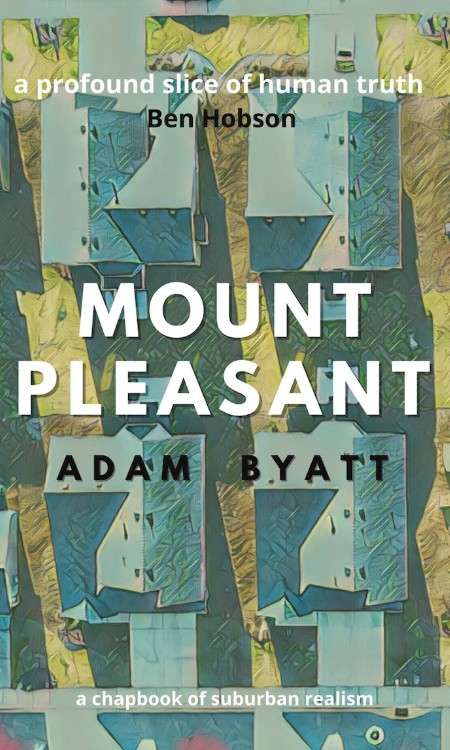

But as Adam Byatt explores with intense empathy and sparkling nuance in his chapbook, Mount Pleasant, the stark reality is that all the PR in the world, inadvertent or otherwise, outwardly or inwardly directed, can’t always paper over the grim, unwavering realities of life.

Not even a name change can do that it seems.

The title is drawn from a now renamed suburb in Western Sydney once known as Mount Pleasant which Byatt observes was nothing of the sort, a place of “violence and dangerous youths” which remained exactly the same despite the council’s best efforts to pretty up its image with a bright new moniker.

A resident of Western Sydney which, for all its many riches and vibrancy of its public life, suffers from an enduring image problem, Byatt was inspired to write a series of beautifully-judged stories based on the fourth album from Sydney-based post-rock band Solkyri who Byatt notes were inspired in the writing and recording of their music by “themes of deception, deceit, and false facades”.

“The girl like the way frugal felt in her mouth. It was a pleasant sound to taste and made her want to fill her mouth with more hungry words. She learned new words to do with money. She elongated spendthrift and emphasised the ffft at the end. Prodigal was shaped contemptuously with a Sunday School cadence. She accentuated P-words with an explosive pop of her lips. Profligate. Pecuniary. Poverty.” (P. 9)

The music is indeed compelling and well worth a thoughtful listen, but it is what Byatt has done with these evocative songs in Mount Pleasant that is the focus of this review.

His goal in writing these arrestingly evocative stories was a simple but searing one, to bring alive the people of a suburb who grapple with enormous challenges but who, like all of us, simply want to be feel safe, loved, valued, hopeful and able to be their authentic, unvarnished selves, both to the outside world but also to themselves which is often where the greatest condemnation occurs for all of us.

It’s something Byatt emphasises in his introduction to this peerless collection of stories which began life on his blog, when he writes that we “love falsified versions of ourselves” and by so doing, “deceive ourselves in the process.”

All of the vividly-realised characters in the nine stories contained in Mount Pleasant, none of whom are ever named but are no less richly memorable for that, are as human as anyone else, experiencing as Byatt notes, “joy and laughter, doubt and confusion, fear and uncertainty, revelation and resurrection” and daily having to make an accommodation with the gulf between their external realities and their inner narrative truths.

The two rarely match for many of us if we are truly honest, but it is in places like Mount Pleasant, shiny new name notwithstanding, that the battle what is and what we wish for becomes almost titanically difficult with life offering precious little diversion from grim reality and searingly awful certainties.

Take the final two stories in the collection, named, naturally enough after the final two songs on the album.

In “Well, Go Well (Interlude)” we bear uncomfortable witness to an abusive husband doing his pathetically self-serving best to defend the utterly indefensible as he says to his wife, after yet another beating it seems, that he is a good man, that the fact the violence occurs is her fault and that she bears responsibility for what he does.

Herein lies the most brutal and shocking of the stories that each of the people in these stories tell each other; he is manifestly and brokenly and horrifically in the wrong, but in his attempt to square an unpalatable internal reality with the graphic truth of the outside world, we see how manifestly people can lie to themselves and to others in the service of manufacturing an acceptable and livable life story.

The story though is affectingly flipped on its head in the following tale, “Gueles Cassees (Broken Faces)”, in which we are taken into the world of the wife and mother who has presumably has to deal with not just the abuse but her partner’s projection of blame for it, and who is struggling to find a way to accommodate the harsh truth of where she lives and the monster in her home with her poignant aspirations to love and care for her small child as she takes them to playgroup.

Hers is a Herculean effort of reality shifting as she does her best to make accommodation with the truth behind her appearance at the playgroup; this is an act of selfless love for her child but also of brazen necessity because what choice does she have in that moment but to get through the day and do the best to pretend her life is better than it is.

You get the impression, in writing that is sharply observant, emotionally resonant and gently but harshly truthful, that those around her know the truth of her story but for her sake, and likely theirs too, choose to play along with the story as it is projected and lived because to do otherwise is to fracture that tenuous divide between what we wish for and what we, sadly, what we have got.

“In the early hours of the morning he had laid awake, listening to the hush of waves and the murmur of traffic on the highway. He imagined it as the noise of miniature mining machines carving open the layers of his ribs, strip mining the walls, counting each one as a deeper layer of strata without attempting to determine the origin of who he was; pillaging his flesh for someone else’s purposes.” (P. 51)

There is a great deal of grim reality in Mount Pleasant but that does not render it in any way an unbearably hopeless and unrelenting read.

For a start, Byatt is too talented and insightful a writer to ever be that one-note and narratively obvious, but beyond that, he is also acutely aware that human beings are far too complex and hopeful to ever lose themselves irretrievably to the hopelessness of a situation.

Even in the very worst of circumstances, where palpable, actual change seems to be far beyond the realm of any kind of livable possibility, people actively work to retain some sense of hope, of burbling, never-say-die optimism such as in the first story in this luminously alive collection of stories, “Holding Pattern” in which two kids make magical make-believe worlds for themselves as they, and their parents tell themselves their current life-worn circumstances are only temporary “‘Til we find something better'”.

Again and again we see this pattern repeated in prose both brutal and yet hopefully brave.

No matter how dire the outside world may be, people such as the wannabe theatre denizen of “Potemkin” or the young guy in “Pendock and Progress” trying to find the good – his dad found and repaired a bike for him, giving him vitally-important freedom of movement – in a dark and terrible place (his father beats him).

Some may pity these characters scornfully as using pretend and make-believe to escape unremitting awfulness, cursing them as pathetic creatures unable to face the truth, but that limited, cruelly inhuman and insufficiently empathetic perspective ignores the fact these are the bravest people of all – each day they look at the very worst of things, at the bleakness of life and tell themselves about what is good right now and how much better it could be one day.

That is, by any estimation, a testament to the towering power and promise of the human spirit which is why, grimly realistic though it is, Mount Pleasant, written with searing insight and a richly optimistic (though tempered by reality) understanding of the human condition, is far more hopeful than it might first appear, asking us to imagine not just what is right now but what might be, and how we might take that journey to the future, better version of ourselves.