You have likely read this type of novel a thousand times over.

Couple breaks up over reasons devastatingly huge and languishingly trivial, one half of a once-tonight partnership finds themselves reeling and without initially wanting to, finds themselves being forced to reinvent themselves with heartwarmingly and predictably uplifting results.

It’s no surprise that we like these sorts of stories because they reassure us that life can not only go on after romantic trauma but that it can be even better than it was before; when you’re at the bottom of the canyon with no clear way out, you need to know there is a path out of your misery.

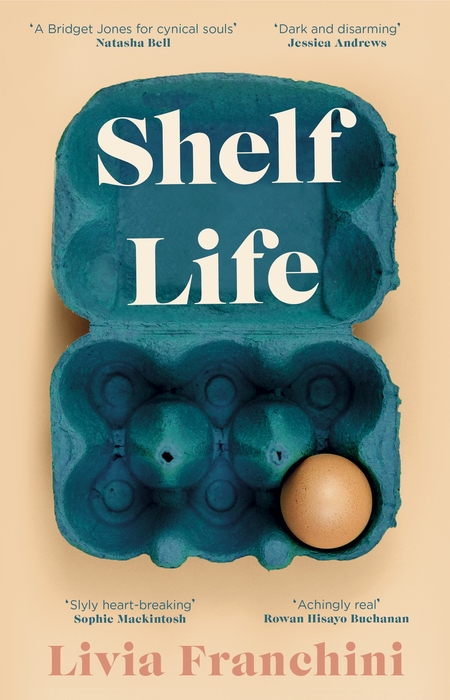

Shelf Life by Livia Franchini takes that well-spun idea and runs in an altogether darker direction with it, cleverly executing on it in imaginatively key ways while something losing the emotional accessibility on the way.

There is no mistaking how much of a fresh perspective this novel brings to a well-loved and much travelled genre.

In Shelf Life Ruth is cast aside on one unexpectedly tempestuous when her boyfriend of ten years, Neil, decides he has had enough of Ruth’s not loving him enough and believing in him enough and walks out the door.

It all seems very sudden and impulsive, the straw breaking the camel’s back all of a sudden and with much warning and you are left thinking that Ruth must’ve had a key role to play in the relationship’s catastrophic single night breakdown.

“My eyes fly open on the upper deck and I am back in our flat; it is still night-time and I’m scared. He always fell asleep before I did. I fell asleep listening to his steady breathing. Now I am awake at two in the morning because the shower is dripping and it’s driving me fucking mad.” (P. 18)

But then Franchini upends things completely, switching back and form in time and between conventional prose, email and phone texting, to explore how complex people and thus their relationships are and how what we on one occasion is far from being the full and expansive story.

One key constant from the genre’s well-stocked larder of narrative ideas is that Ruth has had her life royally trampled on and that she must start all over again to build a life from scratch.

It emerges that Ruth is quiet, introverted and shy, not the kind of person who likes parties or mixing with people and who had happily subsumed her entire life into her coupledom with Neil.

So far, so standard.

What becomes clearer as the story goes on is that Neil is not the self-aware, modern and emotionally in touch guy he first comes across as; in fact, as we become party to old text exchanges between Ruth and Neil, and email chats between Neil and a number of women he’s trying to attract the attention of on false pretenses, it’s obvious that Neil is not a very nice guy at all.

He is actually quite stalker-y and sleazy, a misogynist in thinking, caring man’s clothing, who fooled Ruth – we see how they came together and let’s just say, it’s darker than Ruth knows or suspects – into believing he was her only one until he decided he wasn’t any longer.

Ruth then falls into the more familiar territory of the wronged party and much of the book documents the often unorthodox ways in which she tries to remake and define herself in ways that do not rely on any one man.

That may sound reasonably straightforward but it’s anything but in Franchini’s hands; in her quest to be resolutely honest about how dark the human heart can be and how even innocent parties have some form of blood on their hands, she ends up filling Shelf Life with less than likable people.

That’s fine as far as it goes because we don’t have to like the people in a book as long as there’s a compelling reason to keep reading about them.

Whatever that compelling reason is, however, gets lost in the tonal and storytelling style shifts that take place in the novel which, while they are inordinately clever and boisterously imaginative, leave you feeling emotionally invested in the outcome of the narrative.

So busy and frenetic does Shelf Life become later on, especially with the italicised dream sequences that are supposed to give you a window into Ruth’s soul but which come across as overly messy and disengaged from the wider storyline in which they sit, that you almost cease caring about where Ruth is going to land.

It’s too much in too manic a style of delivery, and while it is inspired and points to Franchini for not being a prisoner of narrative convention, it ultimately leaves you feeling like you don’t care enough about Ruth to hang in to the end which is increasingly off kilter as it races to the finish line.

“Flesh closes around my throat, rubber skin pulling my chin open, seawater in my mouth, as his knee snaps my spine backwards, as my body, released, floats downward, until it reaches the ocean’s bottom.” (One of Ruth’s dreams – page. 174)

It’s a pity because framed by the items on a shopping list left behind by Neil on the fridge, a list created by their coupledom and merged culinary preferences, Shelf Life is a really clever conceit that takes a well-loved premise and has all kinds of darkly insightful fun with it.

As a rumination on who we love and what compels us to love them, it is realistically brutal and truthful, admitting that even the most wondrous of coming togethers is tainting by the flawed stain of our humanity.

This is especially so when someone has driven the relationship into being by deceit and manipulation, two things with which Neil is very much acquainted and of which Ruth is, in lots of ways, a victim, cast aside at 30 when the man she thought she loved tosses her aside for greener, if twisted, romantic pastures.

Shelf Life has a great deal to say about the broken expressions of the human condition and how we recover from romantic trauma, and really trauma overall, but much of its impact is dissipated by a delivery style that while ambitious and welcomingly original, buries much of its hoped-for emotional resonance under a mountain of too clever by half writing that aims high, both in its writing and its narrative intent, but which ends up feeling as emotionally shallow as Neil’s slimy, slippery heart.