It’s not an unusual thing to be so completely drawn into the lives of a book’s characters that they come to feel like temporary flesh-and-blood fellow companions on the journey of life.

Far from merely residing on the pages, these people are as real as your own family and friends, each with their own wants, needs, loves and fears and each, eventually, as dear as anyone you have met face-to-face.

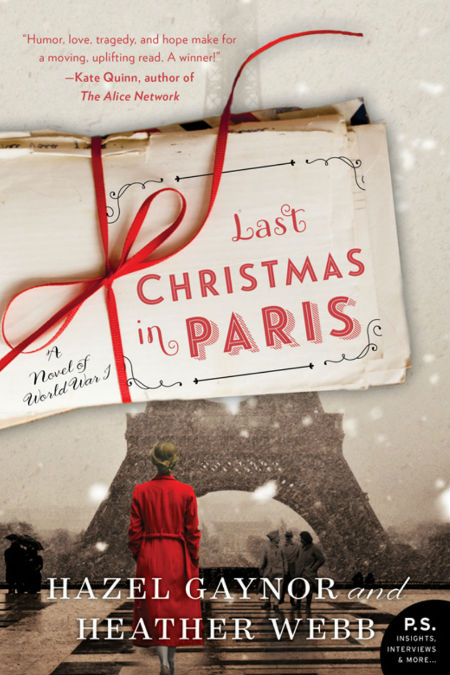

A good book’s characters should feel exactly like that and so it is with Last Christmas in Paris by Hazel Gaynor and Heather Webb which takes us into the lives of Evelyn aka Evie Elliott and Thomas Harding as they endure the horrors and loss of the War to End All Wars from 1914-1918.

The passage of this emotionally rich and historically accurate novel follows the loss of innocence that accompanied everyone who greeted the start of war on 28 July – the UK, from which Evie and Thomas hail officially entered the unprecedented conflict on 4 August 1914 – as a minor skirmish that would be over by Christmas that year only to find it drag on for over four long years with near-uncountable loss of life and the destruction of a treasured and irretrievable way of life.

Meticulously-researched, Last Christmas in Paris uses the letters, telegrams and notes between Evie and Thomas, along with a great many others including between Evie and her brother Will, Thomas and his newspaper-owning father, and with Evie’s best friend Alice, to tell the story of what happened to a nation and a continent through the eyes of two people who have known each other since childhood.

“(Evie to Alice – 5 November, 1914) The problem is I have too much time to dwell on things. I can’t picture what war looks like, or where the boys are. When they were at Oxford it was different. I knew the dreaming spires and the Bodleian Library. I spent lazy summer afternoons punting on the Cherwell. Now, it feels as though they have gone to the ends of the earth—to some undiscovered land I know nothing about. And I can’t help feeling terribly afraid.” (P. 25)

It is, in many ways, a very hard story to tell.

History has a way of inadvertently romanticising the unromantic, as the stark realities of life for the people who endure an event, and if ever there was an endurance test for the time it was World War One, end up playing second fiddle to dates, landmark events and bloodied statistics.

It’s inevitable as people pass away and can’t tell their stories directly that the humanity and truth of what they experience isn’t as loud as the nuts and bolts of history itself, which is why novels like Last Christmas in Paris are so vitally important.

Drawing from a rich resource of correspondence from the period, along with journals and media accounting – though the latter especially must be taken with a grain of salt since censorship reigned supreme during the war and what was expressed on the page rarely matched the truth on the ground at places like Verdun and Ypres – the novel reflects what life was like for people during World War One and why the damage the conflict inflicted went far further than the mud-soaked battlefields upon which many senseless battles were waged.

The loss of so many tens of thousands of lives was unbearably tragic in and of themselves, but what concerns Last Christmas in Paris most of all is how these deaths, and the war in which they take place, affected people back at home and those on the European continent who survived the horrors to which they bore direct witness.

While the novel is at heart a romantic one, anchored in the war at one end and Thomas’ farewell trip trip to Paris in December 1968 and centred on the Christmas period when people’s thoughts and heart inevitably turn to those they love, its narrative is as substantial as it is starry-eyed with the developing romance between Evie and Thomas set against seismic events that would test even the most enduring of bonds.

The reason why Last Christmas in Paris makes such an impression, quite beyond its dedication to conveying the nightmarish truth of life in those four long years, is that Gaynor and Webb, both highly-regarded historical authors in their own right, bring Evie and Thomas, and those they love and value, to life in such a vividly affecting manner.

These aren’t simply two people who function as conduits for the events of the time.

While that is an element of the emotionally resonant storytelling, without which much of the novel would lose its power, Evie and Tom are two very real people whose experiences matter in and of themselves.

That they are representative of the people of the time, who endured privation and loss on a scale not matched or exceeded until World War Two (though you could argue that the Spanish Flu which cruelly followed WW1 made things far, far worse), the interest of Gaynor and Webb seems to be in bringing an authenticity of lived experience to an event which too often these days, seem distant and remote, a collection of significant dates and nothing more.

By telling this story through the persons of Tom and Evie, we come to understand why the war was so overwhelmingly destructive but we also come to see in a way that seizes your heart most unexpectedly, how love, real muscular, in-the-trenches (literally in the case of Tom) love can withstand pretty much anything this blighted world of ours can throw at it.

“(Thomas to Evie – 1 January, 1916) Thank you, as ever, for your encouraging and kind words last month. A heavy cloud has hovered over me these last weeks, and I have been unable to shake it … Another Christmas at war exacerbated things, but I’m breathing easier now that the festivities , and the incessant reminder of all I have lost, are behind me. A new year lies ahead.” (P. 188)

If, like me, you pick up Last Christmas in Paris thinking it will be a pleasingly lightweight romance to divert from the travails of your life, you will be more than pleasantly surprised to realise what a robust tale of love and life it is.

That it is romantic is unquestioned, but it is romantic in a way that endures despite the horrors of the world and time in which it takes place, meaning that the story of Tom and Evie is far more than just two people falling in love, grand and epic though that almost always is.

If you are even slightly possessed of a sentimental heart and a romantic sensibility, and especially if you are in love yourself or have been or want to be, there is much to love about the way that love slowly but surely catches up to Tom and Evie at a time when you would think it is the last thing anything would be worrying about.

But as Gaynor and Webb makes gloriously and luminously clear, it is precisely when the world has gone to hell and there seems very little to live for, that love and romance becomes more important than ever.

Again, while walks along moonlit rivers and candlelit dinners are one of life’s most beautiful things, they become almost vital and inherently necessary when so much you value hangs in the mortal balance.

Tom and Evie’s love affair, all wrapped up by Tom’s life some fifty years later, is evocative because it takes place against a backdrop that should be inimical to it succeeding but which is in fact the very reason why it takes on such power and urgency and why Last Christmas in Paris is such a compelling read in ways that will stay with you long after the last deeply-affecting page is turned.