This year was a highly unusual year.

I finally started going back to the movies in something approaching normal fashion, and while the choices were a little limited with a lot of the big tentpoles titles such as No Time to Die, The French Despatch and Ghosterbusters: Afterlife all being pushed back later in the year, I still managed to find some great films to see, thanks to a steady supply of indie and arthouse titles.

Even so, the big excitement was looking forward to the releases from June/July on when a number of films I had really wanted to see were going to finally make their way to the bigscreen.

I shouldn’t have voiced my excitement out loud.

For no sooner had I told my partner how busy June onwards was going to be movie wise than we went into lockdown, taking a host of films off the table, seemingly for the duration. (Thankfully many of them were saved up by the chains in Sydney and Melbourne which means that three weeks after lockdown ended, at the time of writing in early November, the choices are considerable.)

Fortunately I subscribe to a lot of streaming services which meant that either the distributor released them online as well as in cinemas (elsewhere in Sydney was unaffected) or the cinema chains, all of whom have their own online platforms, accessible by means of my memberships with them, who rushed films onto their platform for the lockdown crowd which was significant. (Sydney and Melbourne are Australia’s two biggest cities so the loss of bums on cinema seats was enough motivation to get them onto streaming services.)

These two ameliorating measures meant that I got to see films that I would otherwise have missed, softening the blow of missed films, and meaning that I got some escape cinematically from a tough year and FOMO was assuaged enough to make it bearable.

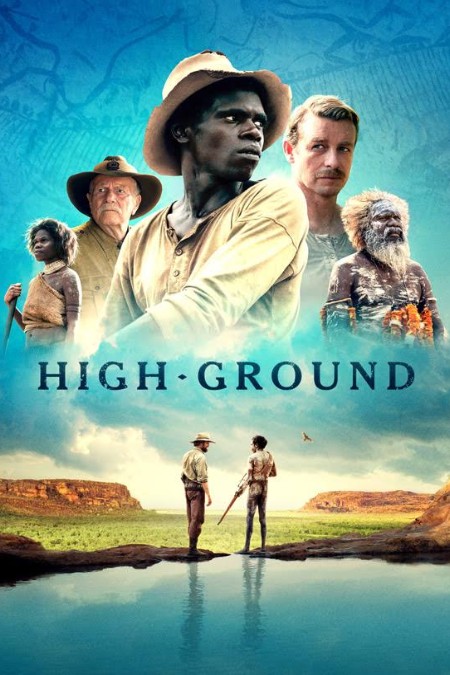

This film, which places First Nations culture, from its language to music to its close bonds to family and Country, front and centre, is one which, apart from tell an enthrallingly gripping story of loss, revenge and squandered, wasted possibility, is a revelatory endeavour, seeking to expose the dark underbelly of Australian history so that, hopefully, some healing might come.

Certainly, in the context of heated debate about Australia Day vs. Invasion Day and the declaration of the Uluru Statement of the Heart, and overall need for Australia to face up to its bloody and violently racist past, High Ground‘s release is timely.

It is a film which does not pretend everything was, or is okay, it is clear that there are no easy answers to entrenched, cruel prejudice and rampant colonialist injustice and that true reconciliation and healing can only come when the truth is revealed, faced up to and we understand the depths of the wound that must be addressed in a country with more blood on its hands that it would care to admit.

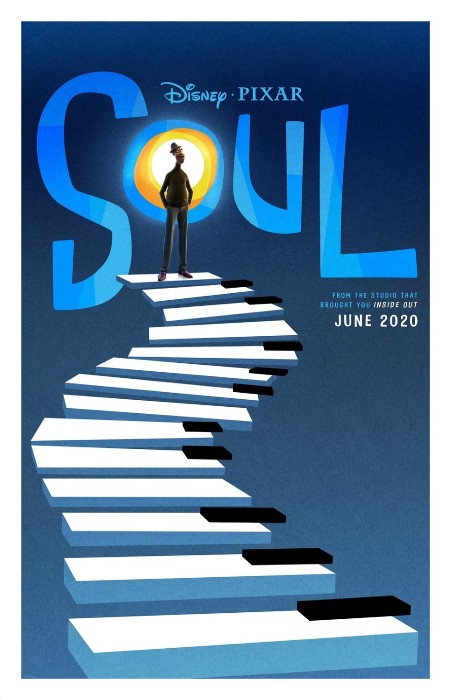

The brilliance of Pixar is that it not only accepts that life is is fiendishly and confoundingly complex while also being delightfully, exuberantly rich with glorious possibility, but that it finds a way to simultaneously, and with great impact and meaning, communicate this to adults and kids in ways that really get the message cross without once feeling ham-fisted about it.

That makes sense – Pixar is, and has never been, one for glib easy answers and yet nor does it wallow in pretentious complexities for the sake of it.

Rather, as Soul inspirationally and emotionally makes clear with luminously lovely animation, sparkling characters, an engaging narrative and visual and dialogue inventiveness, it strikes a balance between deep, thoughtful pondering and accessible articulation, giving us in this immensely rewarding instance, a film that makes you realise life can be beautiful and vivaciously alive but that it’s not a one size fits all, with all of us capable of finding and living our “spark” in ways we never thought possible.

As events race seemingly out of their control and comet fragments, some as big as football stadiums, destroy cities all across the world, all breathlessly reported by a media grappling, as is everyone, at the enormity of what this comet means for life on earth, we are thoroughly invested in where John, Allison and Nathan, who gets his own moment to shine when humanity does the expected and does evil in pursuit of self-survival, will end up.

These people matter, and while the spectacle is very much horrifyingly in place and we see, as expected, the very best and worst of humanity – when heroic things are done by the way, they are done in a way that suggests people simply doing what is compassionate and selflessly right as when John rescues a person from a car as molten lava fragments reign down upon a freeway full of sitting duck cars – we are invested because we bear witness to people like us reacting as we might.

It grants the film a luminously engaging human dimension that a great many disaster films lack, and while they are admitted a lot of voyeuristic fun to watch from the safety of your loungeroom or cinema seat, the truth is when they have as much authentic humanity in them as Greenland does, they are a thousand times more enjoyable to watch.

Greenland is a more than worthy addition to this experiential genre, delivering not simply spectacle, thrills and special effects galore, but an affecting sense of searing humanity, of real people like us in the firing line, bringing the story alive in ways that will not only have you on the edge of your seat but reach deep down into your soul as you confront your very worst fears in a way that feels uncomfortably real and rewardingly true to life.

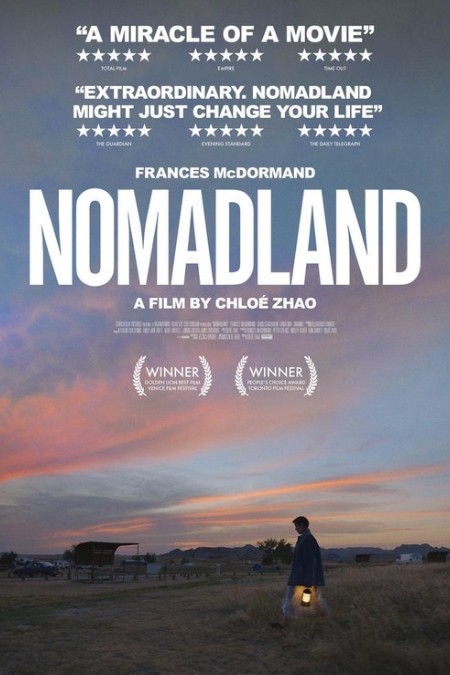

McDormand’s performance is powerful, as is that of David Strathairn, a man she comes to know and who comes to care for her a great deal in a way that Fern may not be ready to deal with, caught up in grief as she is (though Nomadland does show her gradual journey through that in ways that are quietly, powerfully moving), and it is because of McDormand’s commitment to an authentic performances that matches the real people around her, that the story of the outsiders society has left behind, is so impactful.

Nomadland is, simply put, beautiful beyond words.

Possessed of arresting cinematography, courtesy of Joshua James Richards, and a screenplay happy to take its time, the film doesn’t pretend there is anything romantic about the deprivation and poverty and grief of the Nomads but then neither does it ignore the close bonds and friendship —- poetically meditative and emotionally powerful, Nomadland is exquisitely, movingly good, a story that celebrates the very best of resourceful and caring humanity even as it boldly and honestly depicts how society has failed people who by rights should living their very best days at the ends of hardworking, giving lives but who instead must scrabble to survive in a world that seems to have forgotten them.

There is so much aching beauty in Supernova, from its depiction of a devoted, mutually supportive romantic relationship to the unprepossessing gorgeousness of the countryside that means so much to Sam and Tusker but there is no much impending sadness and loss, the kind that is so poignantly expressed that you gasp at the overwhelming of emotion that slowly but powerfully creeps up on you as this nuanced but impacting film sagely and knowingly walk towards its final act.

As goodbyes go, Supernova is a doozy, a grand coming together of all the love and hope and delusion and sadness and regret and mourning that humanity is capable of in the form of two men and a relationship that means the very world to them and whose passing, when it comes and it is sadly coming soon, will be the end of so much with no real sense of how you move beyond it.

This is life as it all too often must be lived, and Supernova captures it all in quietly harrowing detail, offering up a heartfelt exploration of what it means to come to the end of very much loved and valued thing, of the loss of one’s self but all the attendant relationships that define it too, and how you can possibly put one foot in front of the other when there is no certain what will be there when you put that foot down.

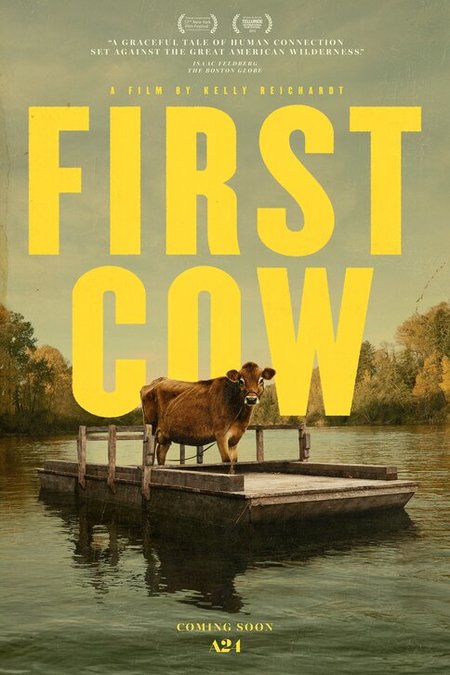

In a slight narrative than never really ventures further than it has to, and honestly given First Cow‘s focus is on friendship, connection and the simmering origins of the American Dream, it is fine just as it is, what really grabs your heart is the fiercely quiet bond that binds these two quiet different men.

Reichardt takes her time letting their tale be told, allowing all the natural rhythms of human life on the frontier to have their space to breathe, allowing audience to subsume themselves in a world which, even then, talks big but delivers little and whose day-to-day hardships and banality grant some grounded humanity to the glowing mystique that still accompanies talk of frontier life.

As much heartfelt love letter to the power of human connectivity as it is a meditation on what drives King-Lu and Cookie to do what they do, First Cow is a gentle slice of beautifully-wrought drama that uses landscape, music, slow arcs and an unhurried storytelling style to remind that big and momentous things such as a life-changing friendship often take place in the unassumingly banal of circumstances.

It is a gorgeously-realised look at the beginning of the American Dream, a wholly unique idea that rests on a need as old as humanity itself – to be known and understood, cared for and sustained and to have someone else have your back no matter what, all ideas that sit at the very heart of First Cow, a film that for all its understatedness has a great and mighty tale to tell, one whose truths resonant down through to the present day where the need to be connected to others remains as necessary and parlous as it ever was.

In contrast to the natural response to this kind of premise which is ratchet up the pressure over and over and over again until the music is blaring in alarmist fashion in a frantically over the top bid to play up the epic nature of this most ethically confronting of conundrums, Stowaway recognises that the true drama, the actual emotional resonance of the piece is to be found in the small, quiet moments wherein lies, rather counter-intuitively, the greatest import.

It’s in the hushed conversation between David and Zoe, or the agonisingly resigned sharing by Commander Burnett that there is no readily apparent to replaced the totalled CO2 scrubbing unit and that they will all suffocate months before reaching Mars, that some of the greatest, most affecting scenes of drama take place.

These are the actions of people who know they are almost certainly doomed, who refuse to give up despite the challenges confronting them (though there are naturally moments of dissension) and who are clinging to a desperate hope that says there must be a solution at hand even if it can’t be seen then and there.

It is the innate decency and humanity of the characters that forms the beating heart of Stowaway, a film that sustains a blisteringly intense and emotionally impacting sense of will they-won’t they-how can they over 116 perfectly-judged minutes, all of which are used to maximum effect and which explore in ways that will seize your heart and soul ever so quietly but devastatingly effectively what it means to truly give yourself up for your fellow human being and if there is any way to have your survival cake and eat it too or if life is such that it is either this OR that with no negotiation to be had.

If you have ever been lost in the seemingly unending miasma of grief, you will be all too aware of what it is like to feel as if your pain and confronting sense of loss has no possible end; Land acknowledges this wholly and without reserve, but it also offers up hope and an assurance that one person’s considerate kindness can make a profound difference to someone trying to claw their way back to whatever it is passes for normalcy in their life these days.

What emerges most strongly, besides Miguel’s transformative kindness and his willingness to respect without reservation what Edee wants every step of the way, is Edee’s tenacity, her will to stay the course.

She is challenged beyond measure by her grief, the elements, her inertia and a grinding sense that what she thought was a way to fix things may simply be making them worse, but she hangs in there ultimately, held aloft by a will to live that defies other urges within her, the kindness of a selfless man and a sense that maybe life has something left to offer her after all.

Land‘s great gift, apart from sweepingly limitless cinematography and minimally beautiful music that you can get lost in just as Edee longs to do, is that it never once proposes easy solutions nor pretends that the road out of grief is an easy or simple to navigate one.

It is hard, it is not linear and it breaks your heart over and over again, and Land perfectly reflects all of that, but you do eventually emerge from it, something we see Edee begin to do but only after a great deal of heartache, tenacity and effort, and most crucially, the unconditional love and support of someone who has been there and understands what it takes to find yourself after so long lost in the dark passages of life.

The Mitchells vs. The Machines

Wait, there’s literally no way you can possibly imagine just how perfectly put together, how heartfelt, clever and manically funny The Mitchells vs. The Machines is; so perfect is in fact, and so packed with comedy gold, both visually and verbally, that you have barely recovered from a particularly genius moment when another comes racing up hard on its heels.

The magical thing about one of the best animated feature films to come along in a while, and yes, it gives Pixar’s best a run for their money, is that also packs a huge emotional punch.

It is, thank the animation gods, both guffaw-heavy funny and heart-rendingly touching, delicately and yet frantically balancing with attitude between runaway hilarity and Kleenex tissue-requiring poignancy, the kind that doesn’t feel like someone unleashed a mass of schmaltzy fromage into your very silly narrative.

The Mitchells vs. The Machines is gloriously, wonderfully, perfectly good, an animated triumph that never misses a beat, that celebrates weirdness and not quite fitting in but knows that belonging to a tribe really, really matters (you’ve got to find the right one), and that socks it to the would-be robot overlords (some of whom glitch and don’t quite live the revolution as PAL intended; long live Eric and Deborah!) all while flashing a megaton of dazzlingly brilliant animation our way and reminding us, because let’s face it we forget, that having a family is the very best of all things and might just be the difference between freedom and living at the beck and call of a very angry, hilariously aggrieved smartphone.

This is film that wears it heart cleverly on its sleeve and which celebrates its message of openness, understanding and inclusivity with a naturalness that takes you gleefully and joyfully along for the ride, happy to spend time with Luca who, though he might be fired by the naivety of youth, has a knack for finding the very best people to call his friends.

It is these friends, in the end, who unite the two worlds of the deep and the land, but bringing even more emotional resonance to the film is the delightful bromance that develops between Luca and Alberto who come to mean the world to each other, transforming both their lives for the better in the process.

Luca is an unqualified gem, a gloriously good piece of heartfelt animated storytelling which happily exhorts us to “Silencio Bruno!” (tell our inner critic or voice of enervating caution to shut up), which holds thoughtful understanding of the importance and richness of difference up high and which does it all with a vivacity of visual style, rich characterisation and sparkling narrative that will leave you smiling for days after you have had the pleasure of seeing it.

Luca is currently screening, at no extra charge, on Disney Plus.

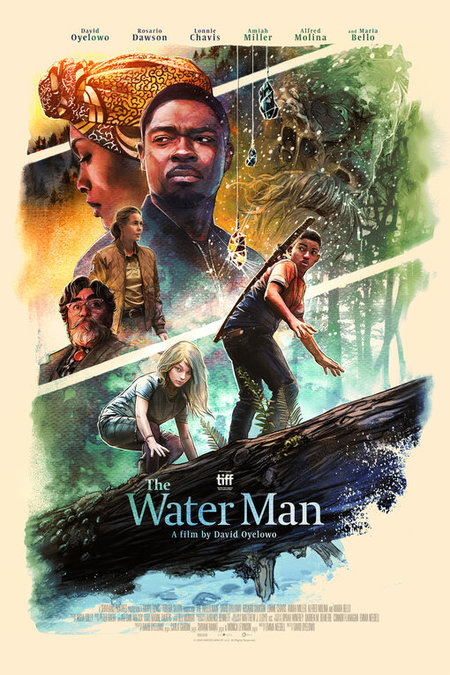

If you have ever experienced a great loss or come close to experiencing one, Gunner’s earnest desperation to have his mother makes profound sense.

Especially when you consider that for many of us the loss of a parent occurs when we are considerably older and at least have the tools to deal with the loss (though, of course, the loss remains every bit as devastating) and yet in The Water Man, Gunner is having to deal with it barely into his teens.

It’s a lot for anyone to handle, with every last fibre of the panic and emotional stress this would cause etched out on Chavis’s face as he seeks to find out if the stuff of myth and legend might just be able to help him with a very real world here-and-now problem.

As the quote from the film at the start of this review makes movingly clear, hope is immensely, world-changingly powerful and even if it doesn’t play out the way you think it will, it can bring about change you never even knew you needed, something to which Gunner can attest by film’s end, and remake your world in ways that make life an infinitely better place than it was before you put all your faith in it and leapt into the void, hoping for a good and perfect landing.

It’s a gloriously good coming together of two richly-drawn characters, augmented by performances which dance between campishly hilarious and meaningfully intense.

It’s this seriousness of approach, that what is being told is an entirely possible if larger-than-life tale, that anchors the inherent silliness of Jungle Cruise, giving it a substantial core that makes all its spinning bits and impossible moments feel entirely, winningly, possible.

You know they’re not somewhere deep down but when you are being entertained this skilfully and well, then who the hell cares?

Jungle Cruise knows you need to run away, that you need just over two hours of brilliantly well-wrought, vivaciously over the top storytelling that takes its beautifully drawn characters, its sumptuously alluringly mythical exposition, and its heart-gladdeningly manically playful plot and runs with it with gleeful gumption and abandon, leaving you at the end as if the world, the tired, constrained, very small world in which you leave, might just be bigger and more magical than you ever gave it credit for.

There are more than a few animated films work that feverishly overtime (and often fruitlessly) to make you feel something, but movies like Vivo (and pretty much anything by Pixar) do it near effortlessly because they prioritise rich humanity, fully-dimensional characterisation and delicate, affecting balance of the serious and the silly, reflecting the fact that life often has both in equal measure and often at the same time.

It recognises too that we need relationships and closeness to others, and that while life’s cruelly sad moments may intervene to rob us of that from time to time, often devastatingly, that healing and hope are possible and keen motivators to get us back to the land of the engaged and the connected where the most marvellous and wonderful things can happen, often when we least expect it.

Possessed of a wondrously selfless heart, a burning need to do the right thing for someone you love, and a manic heartfelt zestfulness that finds expression in Miranda’s superbly alive songs and a screenplay by Kirk DeMicco and Quiara Alegría Hudes that never puts a single toe-tapping foot wrong, Vivo is a balm for the COVID weary soul, a joy for the griefstricken and a beautiful, emotion-infused reminder that life can come back alive when we seek not necessarily happiness for ourselves but for others and that maybe, just maybe, having someone special by our side can be the best thing that ever happened to us.

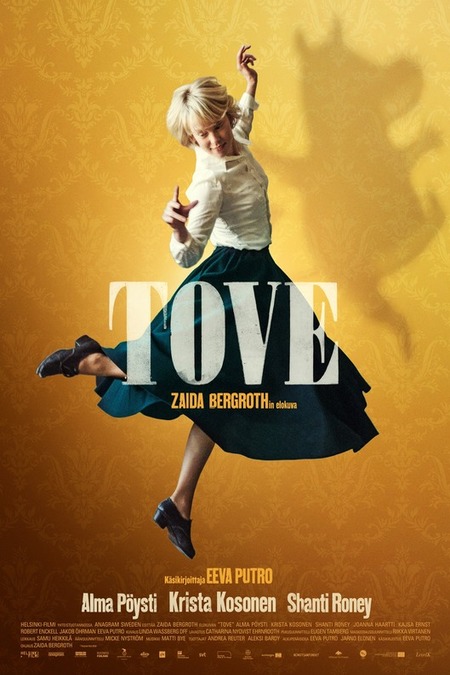

Tove reaffirms that no matter how highly you hold a creation aloft, that it comes always from a very human, often benignly flawed place and that by understanding who gave it life, you can appreciate its wonder, beauty and fun all the more.

Certainly that is the case with Jansson who comes across as a supremely thoughtful, deeply feeling and immensely talented person, someone as capable of writing a comic strip as painting breathtakingly beautiful art, but also a person who, like almost all of us, isn’t ever entirely happy with who she is, what she does and who she loves.

(Speaking of which watching her quietly meet the love of her life, Tuulikki Pietilä (Joanna Haartti) is done with such unhurried grace and touching understatement, that it will make you swoon with its appreciation of how the great and enduring things in life often arrive quite unspectacularly and without a grand entrance).

Far from robbing the Moomins of any childhood lustre, Tove burnishes them further, granting us rich and bolstering insight into the complex person of Tove Jansson, helping us to understand who she was, at least in part, why art mattered to her so much and why its creation was as much about fulfilment as inner conflict for her, and how uniquely wonderful it is that a place as uplifting good as Moominvalley came into place in the personally turbulent years of 1944 to about 1952 thanks to an artist who held so much promise and delivered in ways not even she saw coming.

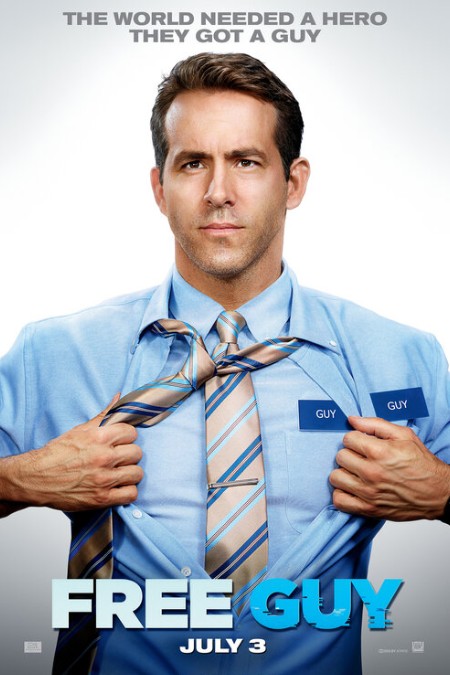

Going from unaware NPC to very much self aware saviour of the say is quite the leap, and not one that Guy manages entirely gracefully.

Yes, he levels up in spectacular fashion, confounding those looking on in gaming circle since no NPC is supposed to be able to think for themselves, but he’s also stricken with the idea that all the certainties of his life have gone, and while a brighter, better future beckons, it is by no means assured and there is a real possibility this great awakening of his might come to nothing.

Thankfully he has Millie in the game with him, and Keys helping from outside so he’s not entirely alone, but he has a lot to deal with in a very short amount of time and the film lets him be both down at heel and hilariously bouncy as only the newly-liberated can be.

While it might look like a extravagantly colourful, cartoonishly violent piece of forgetful fun, and yes, that is true to some extent, Free Guy is overwhelmingly a sweet and wonderful joy, a wisecracking riot of exuberant freneticism that celebrates the freedom to be your own damn self, even if that is a reawakened NPC who discovers in ways that will lighten up and brighten your soul, and provide you with plenty of laughs and swoon-worthy sighs into the bargain, that there is a whole lot more to life than he imagined possible.

If you are looking for violent apocalyptic action, Finch is not the film for you.

The threats are evident and manifest, and punctuate the narrative to heart-stopping effect, but they are not the central story here; rather, what we have is a celebration of the fact that humanity can endure, and make no mistake Jeff ends up every bit as human as Finch in the end, capable of empathy, empathetic care and understanding, even at the end of the world even as if you could be forgiven for believing it to be as dead as the world in which it is increasingly scant.

The real gift of Finch is that, for all its narrative propensity to do so – we have a cute AI-driven robot, expressive dog, funny, bleeping robot in Dewey and a curmudgeonly charmer in Finch Weinberg to give him full name (there’s a nice moment where he gets dressed as a near-miss run for supplies and he attaches his old corporate name tag) – it avoids mawkishness and crass sentimenality.

The emotions on display here are grounded and real, borne of primal adversity and all-encompassing loss that is not surrendered to, though Finch, for understandable reasons, comes close to doing so on a couple of occasions, but rather overcome in ways that suggest as much fragility as strength, all riding on the powerful bond between man and his far-more-than-machine who come to mean the world to each other and who save it for each other in ways that will seize your heart for the duration and well beyond.

It’s the film’s willingness to take its time with exposition and character reveals that gives so much resonance and meaning to the action which comes later; true most of the other MCU’s instalments do invest in character but Eternals goes much, much further, giving real substance and affecting vivacity to the action scenes.

Eternals also does an exemplary job of setting up the MCU films that will inevitably follow, not simply by putting in place the building blocks, both narrative and character-wise, for a direct sequel which is all but a given, especially once you take in the middle and end-credits scenes – yes, there are two of them so don’t race out of the cinema too quickly – but by reshaping the whole idea of Earth and how it came to be and who is out there playing with its destiny.

Suddenly, the MCU is playing on an even bigger tapestry than before – yes even bigger than Thanos and his quick-snapping fingers – and it gives the interlinked movies a much bigger narrative pool in which to play which is going to make Phase 4 of the MCU the biggest, boldest and most impressive yet.

If Eternals is any guide, and we can only hope it is, it may also be the most emotionally resonant too, if the MCU continues to cleaves tight to the character first approach of this deeply immersive film which knows that big and mighty things happen all the time in the world but that they only really mean something if humanity is front and centre, and remains as the driver, not the observer, of any big twists and turns.

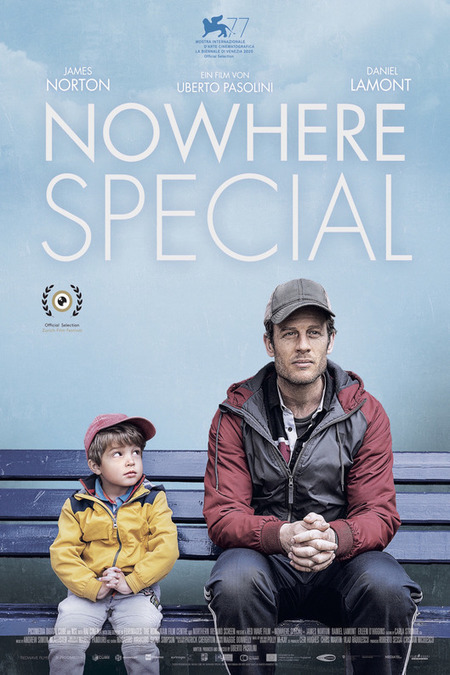

For all of the waiting for the other gigantic shoe to drop that consumes Nowhere Special in the most hauntingly quiet of ways, what emerges from this heartfelt, charming film is a sense of how powerful love can be and how Michael, for all the great loss he soon to experience, has already been given a tremendous gift by his father – knowing what it is to be wholly accepted and unreservedly loved.

While he may not remember concrete things about his early when he is older, he is likely to remember that he was loved and that is greatest joy of this emotionally intense film which even in its final scene goes slowly and softly where others films would have gone for the obvious and the sentimentally overdone.

Inspired by a true story, Nowhere Special is one of the year’s best films, pouring a lifetime worth of love and memories into 96 intensely emotional but marvellously understated minutes that will remind you what real love looks like, that there is hope even in the darkest of situations, and that you should tell people you love them and hug them and be with them while there is still time.

For all its welcome, festively-alive affectations, none of which you will resent for a second and which feel exactly how Christmas should be (at least the version that exists fantastically in our hearts and minds), Single All the Way feels sweetly grounded in the fact that here’s a bunch of people who really, deeply, truly care for each other.

Such is their love and care that they have no trouble showing that to each other, and to Peter and Nick, who are both told in some fairly intense but lovable family intervention-ing that they belong together, which makes all the confected loveliness of it all feel like it’s the stuff of a real family who give a damn about one another.

No caricatures, no bombastic silliness, no cheap laughs – dressed in Christmas trappings so vibrantly colourful it’s like Santa opened up his fantasy sack and just let all the very best festive parts spill out everywhere, Single All the Way is a love song to the season, to love in all its forms and to the idea that you can have what your heart desires, even when, and especially when, it’s sitting right under your nose just waiting for you to notice it.

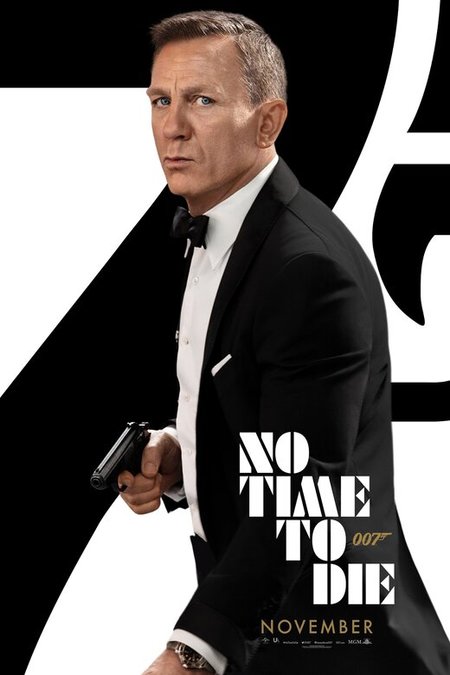

No Time to Die is flawed in certain entirely un-fatal ways, choosing, perhaps understandably – remember again that farewells are not easy to do nor simple to endure – to try to do too much in its 163-minute running time, but by and large it is exactly the time of goodbye that Craig’s anguished take on the character demands and deserves.

We are given the globe-trotting locales, the breathtakingly lush and lavish set pieces and the titanic battle between good and evil, all marred by traces of each other so neither is as cleancut or pure as our morality tale-loving souls are craving; we are also able to spend time with the likes of M (Ralph Fiennes), Moneypenny (Naomie Harris), Q (Ben Whishaw) and the new 007 (Bond has retired and so she gets the number and the gig) Nomi (Lashana Lynch), who sports a fine line in funky sunglasses and seamless capability, who all play their parts in giving Bond the send off he deserves.

These all boxes that need to be ticked, and have to be if No Time to Die is to do its unenviable job of farewelling an era, but far more than that, the film recognises that we can’t just have these elements, richly delivered as they are and be done with it.

We need to feel something, something deep and epoch-ending, and the film delivers that in spades, offering up a dark night of the soul, and then a nascent dawn which does not reach full daylight in quite the way you might expect.

Quite how it finally says goodbye is the stuff of spoilers so intense and unspeakable that they are worthy of being kept secret without a sliver of knowledge escaping, but suffice to say that while you will be enthralled, inspired, alive and engrossed in exactly the kinds of ways that Bond films have always excelled, you will also have your heart ripped in ways that feel fitting for a character who has always worn his suffering and pain like an extra layer of soul-sapping armour.

As farewells go, No Time to Die is impressive bringing together the two Daniel Craig-era parts of the Bond whole – the epic, gigantic narrative battle between melodramatic evil and flawed good and the fragile vulnerability of a broken soul seeking solace and healing though not without missteps – and giving the audience the kind of farewell of which many of us can only dream, flawed at times, and intimately human but fully rounded and truthful in ways that make you sorrowful for what has been lost but quietly hopeful of what may lie ahead in a whole new world that will look nothing like the one that preceded it.

Will the film stay with you long after it’s ended?

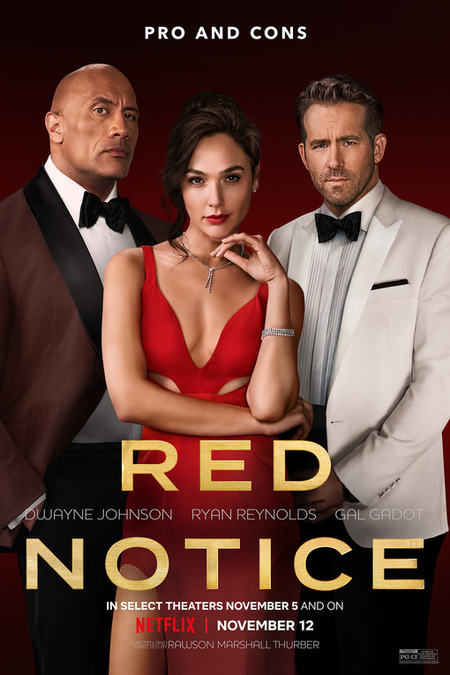

You are supposed at this point to say “NO!” so light and puffy is it, but the truth is, the characters get under your skin, the sheer relief of not behaving properly, even vicariously, is thrilling and the glorious sense of telling reality, which has not covered itself in glory in the last two years, is enlivening in the most reawakening of ways, and you can’t help but to think back fondly on it, like the unexpected friend who turns out with champagne, chocolate and roses just when you think you’ll never enjoy yourself again.

Who can’t be swayed and buoyed by an escapist film like Red Notice which pushes boundaries, strains incredulity and rips envelopes to shreds but has a bundle of heady fun doing it, possessed of characters who are having a ball, a plot that rips around the world in red block letter bombasity, and a ready sense of wit so elastically alive you will happily go anywhere with it, feeling ever more alive aned emboldened as you do so.

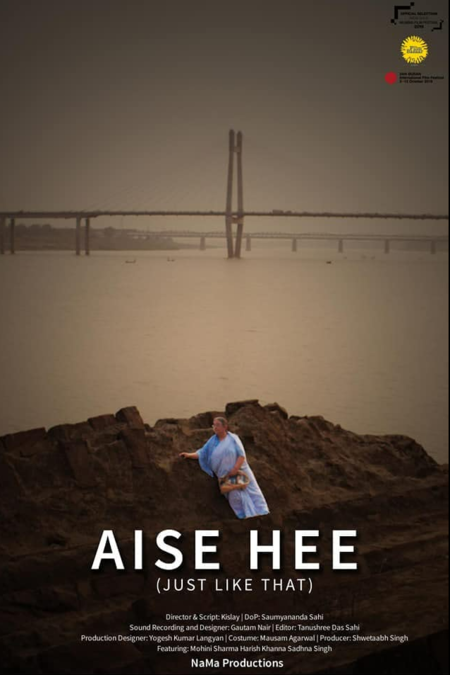

Anchored by Mohini Sharma’s evocatively nuanced performance as a woman deeply unhappy about her old life, quietly happy with her new one, and made miserable when it taken away from bit-by-bit, block-by-condemnatory-block, the film is an intelligently and empathetically wrought film that takes cares not to paint anyone as a caricature, save for the “concerned” neighbours who can’t come across as anything other than hackneyed relics from an age that should be bygone but which is quite patently not.

Even Mrs. Sharma’s son is shown to have some layers to him, a man beset by his own subsumingly constrictive hierarchical expectations and stymied dreams who is lost in his own world of failed hopes, much like his wife Sonia, and children who seemed destined to repeat the mistakes of their forebears simply it appears because the adverse reaction to Mrs. Sharma’s bid for independence gives them no choice.

While Mrs. Sharma does find herself pushed back unceremoniously into a box she does not want to inhabit, the great strength of Just Like That (Aise Hee) is the hope it carries that things can change, that people can free themselves of mindless societal expectations and that being yourself is a thoughtfully quiet joy, not some outward manifestation of demonic possession.

Unspooling its message with sensitivity and care but with a necessary and timely pointedness, Just Like That (Aise Hee) is an immersively affecting film that intimately explores what new-found freedom is like, standing its vivacity and hopefulness in stark contrast against the moribund social conventions of the day that serve no one well and which doom people like the graciously brave Mrs. Sharma from living a life that is uniquely and satisfyingly theirs.

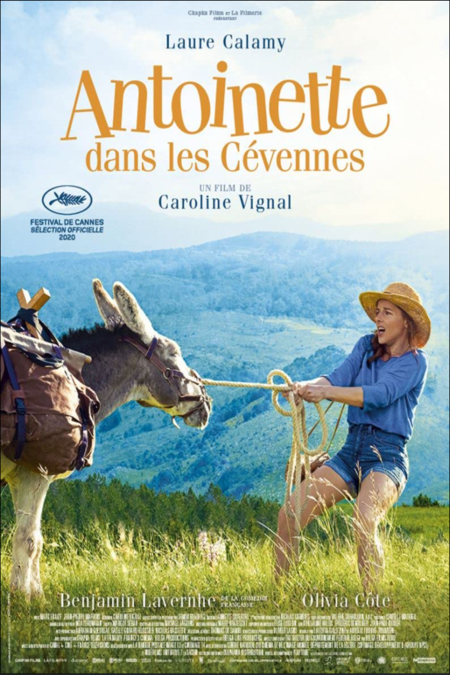

Antoinette in the Cévennes (Antoinette dans les Cévennes)

As romantic comedies go, Antoinette in the Cévennes is refreshingly and pleasingly unique because while there is much romance and comedy, the latter wholly unhealthy for the most part but that is true of most of us at one point or another, there’s also a great amount of relatable humanity.

Who among us hasn’t wished for that magical soulmate to appear and wondered if they ever will? Who hasn’t looked at the less-than-perfect they are with and wondered if there is someone else while doing their optimistic best to make a silk romantic purse out of a sow’s ear?

It’s a common part of the human experience and Vignal expresses it with empathy and heart, making Antoinette in the Cévennes one of those rare films that makes you laugh all while getting inside your heart and mind and making you wonder, as Antoinette, whether there isn’t something more to life and whether you shouldn’t be pursuing it even if it arrives by accident and when you are least expecting it.

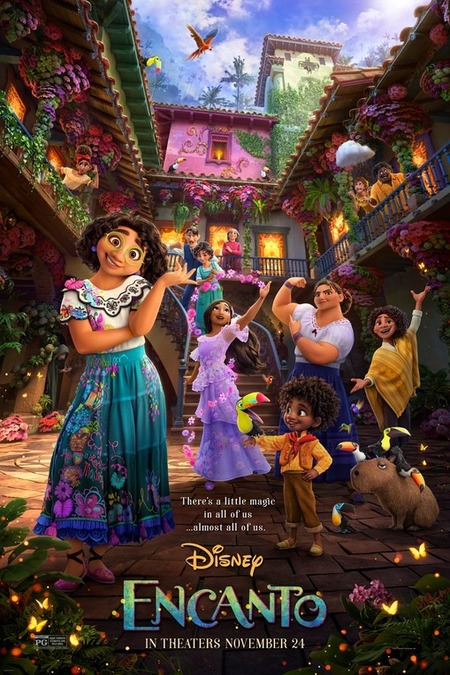

Briefly being the operative word here for while comedy is judiciously used to set the scene and bolster almost uniformly rich characterisation, Encanto is a film that sits very firmly in a poignantly, emotionally evocative place while still remaining accessible enough for everyone to enjoy and appreciate.

Much of this accessibility comes from the buoyantly upbeat songs which, in true musical fashion, belie the great emotional heavy lifting they undertake, each of them reinforcing the fact that while the Madrigals have been blessed, and have in turn blessed others, that there is some great pain and dislocation at their centre.

Much of this is centred in the winningly emotive protagonist Mirabel who has retained the willingness to truly sacrifice herself in the service of family and others that her Abuela has lost and who rather being the end of the family’s miracle, as Bruno’s much-damned precognitive gift seems to indicate, might just be its salvation.

Mirabel is the beating vibrant heart at the centre of Encanto, a film which while it may not be perfect, does a great deal to counter the idea that grief is forever and there is no coming back from the finality of the end, doing so in songs that are richly meaningful, characters that are compellingly and likably alive, and a story that lightly warms the heart while delivering some emotional knockout blows that last beyond the colourful and memorable final act.

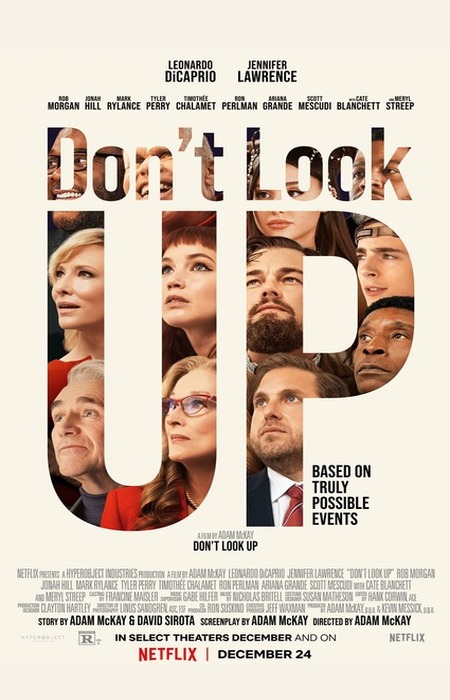

As wake-up calls go, Don’t Look Up is hard to miss, loud, in-your-face and gothically hilarious.

Where it loses out is that in trying so hard to make its point, which towards the end of weaker but emotional potent second half, it leaves you alarmed but not inclined to action, so beaten down by its Cassandra calls to action that you simply want to fire up a sitcom, grab some wine and wish it all away.

Which is precisely what it is saying the problem is to begin with; in the end, while the intent and even some of the execution of Don’t Look Up is laudably good – the final scene of Mindy with his family will break your heart, especially and you know it was all sadly preventable) – and you are left impressed by the scope, acting and intelligence of the film, it fails to land a convincing blow, brilliant satire brought low by trying to do too much too loudly and leaving craving the very superficial escapes we should be eschewing in favour of urgently-needed action.

It’s been one of the weirdest years I’ve lived through and honestly it felt like everything good and normal had abandoned us at times … but still, we had films. We couldn’t see them all because lockdowns and outbreaks, but they were out there somewhere and made me feel like the world hadn’t completely ended. So, here are the trailers for the year, well a lot of them anyway, gathered together by Sleepy Skunk …