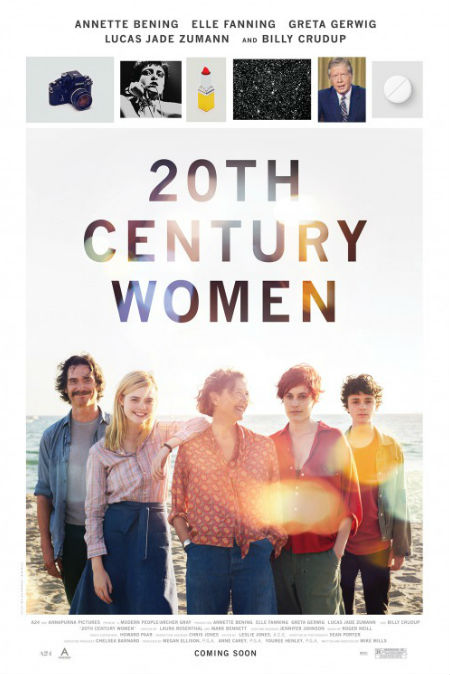

When a film has been as long a time coming as 20th Century Women has been one its long and winding trip to the cinemas of Australia, you begin to wonder if it will match the hype and breathless reviews that precede it.

In many cases, films don’t meet that magically high mark up in the reviewing stratosphere; the good news in the case of Mike Mills’ latest directorial effort is that 20th Century Women matches the superlatives and then some, delivering up a gem of a quietly-simmering slice-of-life drama that is quite possibly one of the best films of the year.

Much of its appeal rests with its willingness to simply tell a story, one that is less a coherent end-to-end narrative, though that exists throughout, than a series of episodic moments in the lives of the people of one Santa Barbara boarding house in the transitioning time of 1979.

In this 1905-era home, which is in a near-permanent state of renovation, Dorothea (Annette Bening in a justifiably highly-regarded stellar performance) is the owner, den mother and quirky aspirant to a happy life, something that she admits is often just out of reach.

Her 15 year old son Jamie (Lucas Jade Zumann), who is close to his mother but like all teenagers also seeking to assert his own independence, arrived relatively late in Dorothea’s life (when she was 40), his birth followed not that long after by his mother and father’s divorce.

With dad pretty much permanently out of the picture, Jamie and Dorothea have each other’s backs, something that Jamie, for all his newfound assertiveness, still very much values.

Dorothea, though besotted with her son and a loving if often unorthodox mother – at one point she challenges her son’s frequent school absences on the basis that not all education takes place inside the four walls of centres of learning – doubts whether she can deliver on his desire to give Jamie a happier life than she managed.

In her quest to build a village to raise her son, Dorothea enlists one of her boarders Abbie (Greta Gerwig), a young Santa Barbara-born and raise photographer battling cervical cancer, and Jamie’s platonic best friend Julie (Elle Fanning), who refuses to have sex with him, fearful it would forever alter their lifelong friendship.

Both take to their roles, first with uncertainty then gusto with Abbie introducing Jamie to feminism, punk music and illicit trips to clubs, and Julie spiriting him away, at his suggestion, on a trip along the Californian coast.

Unsure about what they are imparting to her son, and even more so, how they are going about, Dorothea steps in, asking each of them to pull back and leave the parenting to her.

It’s a back and forth give-and-take approach that speaks less to Dorothea’s fitness as a mother than to her doubts about her own fitness to parent, and while there are tensions between all parties, no bonds are irrevocably severed, with everyone eventually moving in entirely natural ways.

20th Century Women is set in a time of real change, with the upheaval of the 1970s leading people to crave more certainty, a mindset that among things leads to Ronald Reagan supplanting Jimmy Carter, whose Crisis of Confidence speech (15 July, 1979) as US President.

That speech, which features in a key scene where all the members of the household, which includes drifting carpenter William (Billy Crudup), and the extended circle of friends that orbit them sit watching in silence save for a brief, post-speech debate, echoes the uncertainties of everyone’s lives.

It’s not just Jamie, for all the obvious teenager reasons, who is in a place of transition.

Dorothea realises she has only ever chosen safe men to be involved with, not those she actually likes and begins to wonder if has sufficiently enjoyed the world outside, which she samples when Abbie takes her to a club; Abbie meanwhile, who had to return to Santa Barbara upon her cancer diagnosis, frets that she hasn’t lived enough, afraid that she’ll live really live if she stays rooted in their hometown.

William is in flux, knowing his hippie lifestyle of the past, adopted to impress a girl who eventually dumped him after many years of relationship, is not really who he is, and Julie, afraid she might be pregnant, is entirely sure where her 17 year old life is headed next.

While you might well argue that everyone’s lives are in constant turmoil to one extent or another, Mills, who based the screenplay based partly on the relationship between he and his mother, does an exemplary job of knitting together the personal and societal aspects of everyone’s lives, giving us a film that is very much a product of its fluxing time.

Augmenting the skillfully-wrought storytelling, that only really falters from a lack of equal attention to all the characters and relationships in the film – there are perhaps a few too many balls in the narrative air – is a captivatingly unique visual style and a sage choice of musical accompaniment.

Particularly effective are the scenes where people are driving, or Jamie is riding his skateboard down long, lonely car-less roads, all of them accompanied by Roger Neill’s exquisitely beautiful, emotionally-evocative score.

The provide a counterpoint, a quiet wordless break, from the scenes between which are never overbearing but are dense with dialogue and the sense that change is coming and no one is entirely certain what to do with it.

As a paean to a bygone time, it is near seamless, evoking the look and feel of the late ’70s with a keen eye and pinpoint societal and familial observation, but it really excels as an exploration of the way disparate people, temporarily bound together in an unorthodox family, handle the propensity of life to keep changing the goalposts at will with out rule book provided to point to the next step forward.

It is joyfully, meditatively beautiful, anchored by superlative performances, a knowing and insightful screenplay, and a willingness to have some fun with visual styles – the use of still shots, references to 1970s books such a M. Scott Peck’s The Road Less Travelled and judiciously placed narration are supremely effective – one of those films that doesn’t simply live to its promise but exceeds it, in the process providing us with a deeply emotionally-rewarding meditation on life and the way it changes in ways we never see coming but somehow, by trial, error and love & support, manage to successfully navigate.