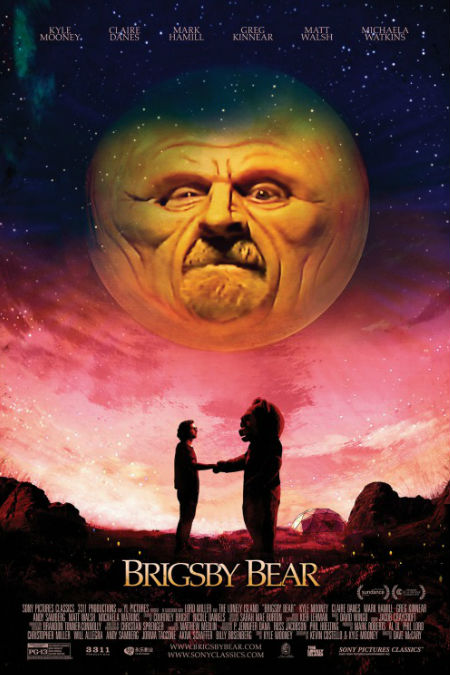

Labelling a movie “sweetly affecting”” is usually a sure way to ensure it is consigned to the depths of the Hallmark channel, wrapped in the patina of a feel-good glow never to be seen again by discerning eyes.

But no matter how you slice it Brigsby Bear is a very sweet film, a heartwarming tale of one young man’s naive yet ultimately rewarding attempts to come to grips with a modern world he knows next to nothing about and with which he has little affinity.

What saves Brigsby Bear from being just another charming indie film, and saves it by a considerable margin, is the storytelling muscularity that lies beneath its undeniably touching exterior.

For this film about fandom and obsession, of love for a TV show and the security and belonging that often comes with this, has as its narrative backbone the story of a young man who finds out in his mid-twenties that his whole life is a fabrication, conjured up for the benefit of his parents who turn out not to be his parents at all.

James Pope (Kyle Mooney) has lived his entire life in a hermetically-sealed bunker, told by dad Ted (Mark Hamill) and mum April (Jane Adams) that the world outside is an apocalyptic wasteland and that he can only venture outside with a gas mask on.

Inside his life is lived almost completely within the confines of a TV show he idolises and is obsessed with beyond all else – Brigsby Bear Adventures, the Ted-made tale (hence James is the sole viewer and fan) of a galaxy-saving bear in a Dungeons and Dragons world that comes complete with weird diversions into maths and geography, flimsy sets, suspect special effects and dubiously over-saccharine acting.

James cares not, minutely dissecting each episode for the forum of which he is a part, his room filled with every possible piece of Brigsby Bear memorabilia from bed sheets to lamps, posters and every episode on VHS tape wrapped around the walls.

The show, despite his parents urging to devote more time to study, is his entire world and James, a man/child with a good but singularly-focused heart, is content with that.

Then one fateful night the police drive up en masse to the desert compound, arrest Ted and April, and whisk James away from Brigsby via the kindhearted, thespian-frustrated Detective Vogel (Greg Kinnear) to his real parents Greg and Louise Pope (Matt Walsh and Michaela Watkins) and sister Aubrey (Ryan Simpkins) who embrace him with open arms. (Aubrey less enthusiastically so than her understandably over-eager parents.)

Quite fairly seeing Brigsby Bear as the tool of their son’s captors, they set about, with the help of therapist Emily (Claire Danes), to steer their son away to a life of outdoor swimming, family events and normality.

What’s missed in this determined tilt at rehabilitation, a fair aim given how disconnected James is to pretty much everything in the modern world, is how much Brigsby Bear is James’ world.

It is his touchstone for almost everything, his way of making sense of the world and without it he’s lost and adrift, until he connects with Aubrey’s friend Spencer (Jorge Lendeborg Jr.) and they decide to make a Brigsby movie.

What follows, and is missed by James’ real parents completely, is that the very thing they’re trying to extinguish from his life is the one thing capable of integrating him back into a world he left as a baby.

Brigsby may, in one very real sense, be the tool of the oppressor – although wisely the script, while not absolving Ted and April of their crimes, does not deem them to be unthinking monsters either, symptomatic of the thoughtfulness and emotional nuance throughout – but it’s what James knows and loves, and in the absence of anything else, his only way to find a bridge into his family and the unexpected world around him.

The script by Mooney and Kevin Costello and the assured direction by Saturday Night Live director Dave McCary – the three are friends from childhood which they spent making short films together – is sensitive, sweet and funny every step of the way while never losing the sight of the fact that James is the original little boy lost, the world he knew gone and the new one he’s unceremoniously given, Brigsby Bear-less and all, an undiscovered country with nothing in the way of a relatable roadmap.

It’s this emotional muscularity, this understanding of what it is to not fit in, that gives Brigsby Bear so much resonance.

Sure you laugh affectionately at the way James apes everyone around him, taking everything said to him as gospel, and his earnestness and childlike glee is infectious if amusingly bewildering to people who, expecting a grown man, get a pop-culture obsessed man-child instead; but ultimately what you see is someone trying to find his place in the world and not always succeeding, until, of course, he finds away to use, unwittingly since there’s not a calculating bone in his innocent body, what he was to fashion what he could be.

It’s serious business for all James’ social faux pas and sweet singularity of worldview; he has been kidnapped, indoctrinated, however much Ted and April cared for him, and lost connection to this family and the world outside, emotionally stunted although not bereft of the ability to relate to other people.

Without putting a foot wrong, and with a keen observance of the way pop culture helps everyone, not just James, to navigate the world – one thread through the movie, where Brigsby Bear is uploaded to YouTube and goes viral, wryly comments on the way this happens for many people – Brigsby Bear is ultimately the story of one lost person movingly finding their way back to the wider world.

The movie is heartwarming, sweet and ineffably uplifting but it is also knowing, authentic and emotionally true, a film that knows all too well how much our sense of the real world depends on made-up or fictional ones – after all, much of our worldview is essentially belief and perception, a thousand miles away from tangible certainty – and how embracing rather than pushing it away, no matter its source, may be just the ticket to finding our way through this confusing mess of contrariness we call life.