If it were possible, and to be fair, she is only one woman (though an extraordinarily gifted one at that), it should be mandated that Jillian Bell be cast in as many movies as can accommodate her.

There is something about this actress, who first made it on many peoples’ radars in 2019 with Brittany Runs a Marathon, that is utterly captivating, bringing her characters alive with an exuberance that is endlessly beguiling.

Whether it is anchoring an major indie hit like Brittany … or delivering a memorable cameo in Bill & Ted Face the Music, being giddily hilarious or affectingly serious, Bell has a way of bringing alive the movies she is in in a way that elevates movies that are sweet and charming but not poised necessarily for classic greatness.

A film like Godmothered, for instance, which hardly breaks the mould when it comes to the “an innocent from a magical realm finds herself in our far more banal and brutal reality and finds a way to change the lives of those around them while also being profoundly changed themselves” genre.

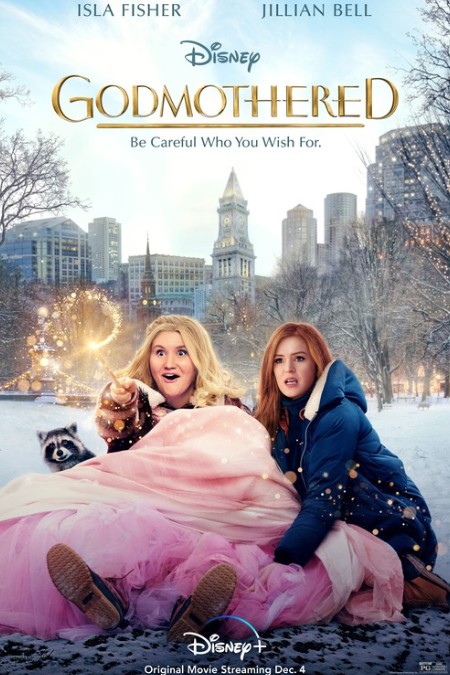

Even so, for all its well-telegraphed tropes, cliches and narrative predictability, Godmothered is a delight, uplifted by Bell as Eleanor, the wannabe fairy godmother of the title and a solid performance from Isla Fisher as life-worn single mother of two and onetime media wunderkind Mackenzie who becomes the target of Eleanor’s earnestly bouyant campaign to stop fairy godmothers going the way of Dodos and answering machines.

Directed by Sharon Maguire to a screenplay by Kari Granlund and Melissa Stack (from a story by Granlund), Godmothered, succeeds of a boundless enthusiasm that suffuses every last frame of this oft-told story.

Much of that comes down, of course, to Bell, who is an overeager fairy godmother who still believes that what they do in peoples’ lives in the mortal realm in very, VERY important.

She is the first to apply to fairy godmother school in the European-like fairytale kingdom of Motherland in decades, her bubbling excitement for her education as a fairy godmother standing in marked contrast to the older students around her, who have been ground down by a calcified curriculum, developed by Moira (Jane Curtin), which hasn’t changed in centuries, and an almost total absence of requests for assistance from people back in our far less magical reality.

In short, just like in The Neverending Story, people have stopped believing, and while Motherland is not about to wink tragically out of existence, it is going to have to repurpose itself as a production line of tooth fairies, something that fills the ever-excitable Eleanor with volubly articulated dread.

She is determined to prove that there’s life in the fairy godmother concept yet, and secretly unearths a letter from 10-year-old Mackenzie who asks for help (and world peace), a plea so sincere that Eleanor can’t resist.

Although she isn’t fully trained in all the spells and rituals of fairy motherhood, she figures enthusiasm for the task at hand, and her noble mission to save her profession will suffice, and so, after rather clumsily opening up a portal to our reality, sets out to remake Mackenzie’s life and in so doing, save her own.

Yes, granted, not the most altruistic of motivations at play here, something that Mackenzie eventually picks up on, but the end result are lives changed for the better, almost by accident it must be said, and a reinventing of Motherland that updates the idea of the love of a man and a gown saving a woman to that woman, saving herself and her daughters.

It is a nice feminist touch that subverts the idea of farytale romance, and while it’s clear that Mackenzie is on her way to falling for handsomely bookish fellow reporter Hugh (Santiago Cabrera), it’s not this nascent relationship that proves to be her salvation from a lacklustre and care worn life.

And that brilliantly reorienting of fairytale from romantic love to faith and belief in your self and those you love is what gives Godmothered a freshness and originality that makes the film a ton of subversive fun to watch.

What also adds to its appeal is the way in which the characters are allowed to exhibit real, affecting emotions.

Far from being narrative-serving cardboard cutouts that exist only to propel the story forward, Mackenzie, and her daughters, and Eleanor, are all allowed to wear their hearts quite affectingly on their sleeves.

That doesn’t mean Godmothered is some sort of searing, raw indie drama that eat your heart out with its brutalist view of the world but it does infuse this happily lightweight and headily lightweight film with a substantial dose of the rigours of the human experience so that the big, bright, redemptive final act actually feels it’s well earnt.

In other words, the happy ever after these characters end up receiving, which again bears little resemblance to fairytale standard, doesn’t feel like an inspirationally feel good tack-on to the story but an authentic finish (and that’s saying something how rewardingly frothy the ending is) to journeys which have involved a lot more than just some hollow words and trite set-ups.

Mackenzie and her daughters, and yes even Eleanor, have gone through the mill and back, and so while the final act is pretty everything you’ve seen in other movies of this ilk, complete with an absurdly public audience, it feels grounded and real in a way you aren’t expecting from a film that initially appears to be headed for a light-as-air happy ever after and not much more.

Ultimately though Godmothered is a fun and frothy and lightly hilarious romp through the human experience that assembles a lot of pieces we have seen before into a film that exudes an excitable sense that anything is possible, thanks largely to Bell’s effervescently gung-ho performance, and that while life might feel like it has defeated us and inertia has won, that we can reinvent ourselves and remake our lives in such a way that nothing will ever be happily the same again.