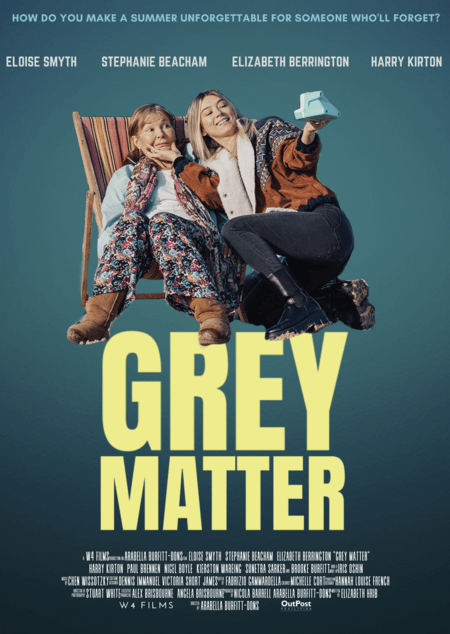

(courtesy IMDb)

What is it like to lose someone before you actually lose them?

Ask anyone who has walked with a loved one through the long dimming road of dementia, and you will hear harrowing tales of what it is like to see that person disappear task by task, memory by memory and to have them, by the end, not even know who you are.

It’s a cruel and thieving disease and it’s sudden arrival in disaffected teen Chloe’s (Eloise Smyth), the protagonist in Grey Matter, in the person of her beloved and feisty Nan Peg (Stephanie Beacham) is confronting because it suddenly puts a full stop on a life that felt scarily limitless and without boundaries up until that point.

In such a freewheeling setting, Chloe felt free to dump her weekend and after school job and to leave school too because she has absolutely no idea what to do with her life; rather than knuckling down though and trying to figure what to do with all the years ahead of her, Chloe instead falls down a rabbit hole of directionless nothing, and it’s not until Peg gets her diagnosis that Chloe is forced to realise that maybe that vast expanse of time that scares her may not be so endless after all.

While Chloe’s mum and dad are supportive – the relationship between Chloe and her mum is fractious, driven mostly by the former snarky interactions with the latter at just about every moment and on every issue – and rally to look after Peg, it is her granddaughter that steps up to the plate and who works to look after her Nan as she slides into the dark recesses of dementia.

What begins as a grudging acceptance of necessity soon becomes something far more intensely important to Chloe who, as she cares for Peg begins to grapple with the fact that she’s a long way from happy and that she has absolutely no idea what she’ll do when Peg eventually goes into care and no longer needs care in her home.

One bright light in Chloe’s bleak world is Sam (Harry Kirton), a sweet young guy whom she meets at a carers support group and who has the patience of a saint as Chloe pushes back against him over and over until she realises what a good and generously caring soul he is.

Where Grey Matter excels, though not always flawlessly, is the way in which it invokes not only the painful loss of someone near and dear to you, but coping with that while dealing with your own mental health issues.

The weight on Chloe as she grapples with her clinical depression at the same time as Peg’s hold on the world around her is lessening by the day is sobering and heartbreaking and it informs Grey Matter with a ruminative sense of the world closing in even as Chloe tries desperately to stop everything folding down on top of her.

The beauty of Grey Matter is that it doesn’t shy away from being honest about the toll that mental health and dementia can take on a person and their family.

Granted, it is too overwrought at times and goes melodramatic when a more contemplative approach, which interestingly ti does employ much of the time, but overall, it captures how dark and sad life can be when any and all markers of hopefulness seem to be absent.

If that all sounds too great a bar to bear a filmgoer, rest assured that Grey Matter doesn’t lose itself in the bleakness and honesty of Chloe and Peg’s world as it is in the first two acts of the film.

Slow, and surely, it begins to let the sun in, to reassure us that while the weight of life at its worst can be crushing, it is not fatal and can be survived and yes, perhaps eventually thrived in.

But this sort of hope, of change and of possibility isn’t without come cost, and Grey Matter is sage enough to know, and to represent, the fact that happy ever after is only ever qualified and not unlimited.

Even so, in its own quiet, quite beautiful but honest way, Grey Matter does offer up hope.

It knows that grappling with mental health issues or watching a loved one struggle with dementia and the loss, little bit by little bit, of who they are, is never, ever easy, but as Chloe moves on, she begins to realise that looking after her Nan cannot be the reason she gets up in the morning, no matter how much she loves her.

When she drops the bluster, and Chloe is impressively and exasperatingly good at it, and finally admits how dire things are for her, things finally improve; perhaps a little too fairytale-ish for a film that up until that point has worn its emotionally heart very much on its sleeve, but you can hardly begrudge the sparkle of hope and possibility when there’s been so much bleak reality leaching at the coherence of Chloe’s family and her own sense of self.

While the film by directed by Arabella Burfitt-Dons to a screenplay by Elizabeth Hrib may feel apt to roam into melodramatic overplay at times, departing from a quietly ruminative thoughtfulness where life feels like its playing out in real time, and it feels under-paced at others, the effect is hardly fatal to the narrative nor to a sense that here is a film that acknowledges and embraces the darkness of life but which also knows no situation is without some redemptive qualities and which pushes its characters slowly towards and through them until they come, changed but still through it, out the other side to whatever awaits them there.