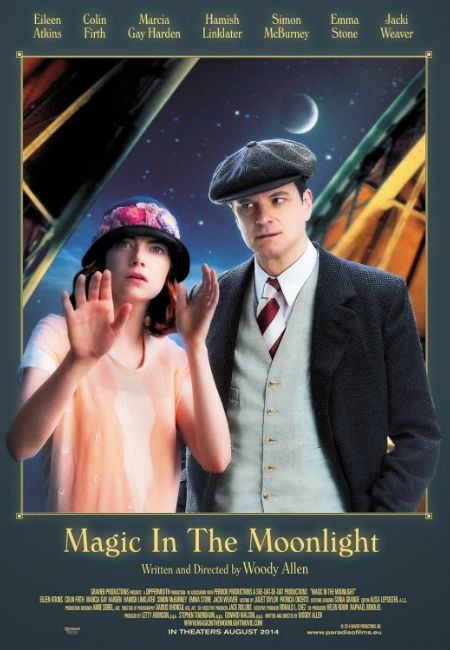

Life is, notes one of the main characters in famed writer/director Woody Allen’s latest love letter to the glories and excesses of the Jazz Age, Magic in the Moonlight, a Nietzchean exercise in self-delusion, with every moment dedicated to distracting ourselves from what the German philosopher called “the horror or the absurdity of existence”.

It may sound like an overly serious, not to mention oddly dour observation for a character surrounded by the romance and endless pleasures of life in the south of France in the late “Roaring Twenties” to make but in the context of a movie devoted to the collective pulling of wool over the eyes of the rich and gullible, it is perfectly at home.

Theirs is, after all, a fairytale existence, doomed to end only a year hence with the onset of The Great Depression – the movie takes place in 1928 at the family estate of the fabulously wealthy Cattlidges, headed by matriarch Grace (Jacki Weaver) – one devoted, almost entirely, to holding that absurdity at bay.

It’s a grand and seductive world, and one in which reputed psychic Sophie Baker (Emma Stone) and her mother (Marcia Gay Harden), have made themselves right at home, a million miles from their deprived lives in faraway Kalamazoo, Michigan.

Essentially now members of the family, with Sophie courted, indulged and serenaded by ukelele by Grace’s lightweight son Brice (Hamish Linklater), and fawned over by Grace who is desperate to believe her deceased husband was not only faithful in this life but happy in the next, and who regards the attractive young American’s spiritualist gifts as a godsend, they are viewed with lingering, though waning, suspicion by Brice’s sister Caroline (Erica Leerhsen) and brother-in-law George (Jeremy Shamos) who summon famed illusionist Stanley Crawford (Colin Firth in oddly stilted form, at least at first) aka the famed Wei Ling Soo, via mutual friend Howard Belkin (Simon McBurney), to see if Sophie’s contact with the spiritual world is “the real deal”.

Crawford, a thunderously angry and unhappy man who fails to see the magic in anyone or anything, and doesn’t so much stop to smell the flowers as stomp all over them – Howard refers to him at one point as a “perfectionist genius with all the charm of a typhus epidemic” – is almost fiendishly dedicated to uncovering the psychic charlatans and fakes of the age, of which there are many, and takes on the assignment with glee, eager to debunk yet another bogus spiritualist sucking off the marrow of the easily-fooled, and desperate to be distracted, rich.

But a funny thing happens on the way to the unerring logical and scientific Stanley’s near-certain (in his extraordinarily self-assured mind at least) unveiling of Sophie’s brazen deception as he finds himself, completely and unexpectedly, falling for the charming and well-poised possible psychic, a woman who is not intimidated in the least by his cynical bluster and swagger.

Uncomfortably torn between believing she is the fake he expected her to be, and that she is, indeed the very personification of all that is good, perfect and magical about the world – this epiphany, while welcomed by him, is simultaneously treated with horror by a man used to a world with sharply drawn black and white parameters and no hint of mystery or the divine at all – he struggles to deal with what may be a seismic shift in everything he believes.

It all makes of course, in Allen’s talented hands, for a mirth-filled comedy, one that pivots deliciously as always on his (mostly) sharply-written dialogue, delight in skewering pretensions of any kind, and well-wrought delineations of the flaws and quirks of humanity.

Unfortunately that is about where the magic ends.

While Magic in the Moonlight is undoubtedly funny, and armed to the teeth with ferociously-observed satire, it fails to fire overall, with Firth and Stone, though reasonably impressive in their own roles, particularly failing to bring any great spark to the relationship that is at the heart of the film.

While Linklater is pleasingly fey at Sophie’s light-as-air beau – “She [Sophie” is both a visionary and a vision!” he happily exclaims to an incredulous Stanley – and Eileen Atkins makes superb work of Stanley’s free-spirited but insightful (and hilariously subtlety manipulative) aunt who practically raised him and knows her way around his arrogantly-armoured defenses, it’s not enough to rescue a film that ends up a pale imitation of Allen’s more accomplished releases.

The dialogue, which does occasionally rise to the beautifully-articulated back and forth zing of movies like Blue Jasmine and Midnight in Paris, limps along, the mystery at the heart of the film – is Sophie a real psychic or not? – is treated with almost Agatha Christie-ish afterthought near the end of the film, and the two main leads never really convince as two highly different people suddenly willing to to see their well-set lives aside for a chance at love true love.

It’s not a disaster by any stretch, since even a less than brilliantly-realised Woody Allen film possesses the power to entertain and amuse, but it lacks the bite, flow and satirical sting of previous efforts, and only serves as a temporary, and quickly forgotten, respite from the absurdity of life that all of Allen’s characters, and one suspects the writer/director himself in common with the rest of us, try so hard to keep at bay.