A lot gets asked of the average biopic.

It must give us a penetrating insight into the life of the subject, preferably something that is unknown (easier with people no longer on the crest of the digital zeitgeist) or at least little known, it must be entertaining and recall those things we love or do know about the person or group, and it must do it in a creative way that doesn’t feel like some tired linear connecting of the biographical dots.

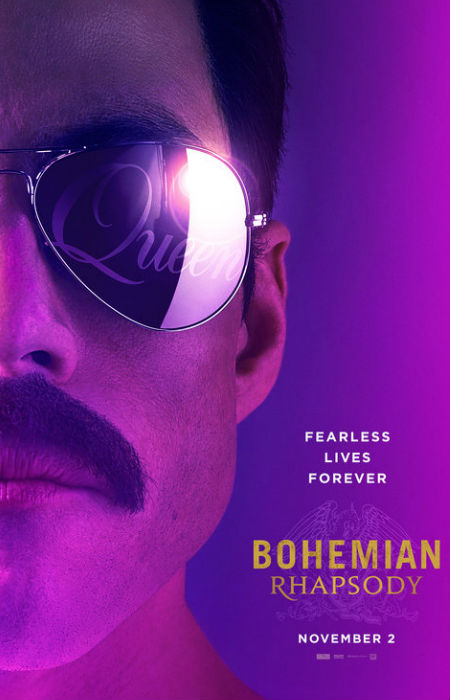

That’s a lot of boxes to tick, and like many biopics that take an expansive position on their subject rather than a more narrowly-focused one that explores a specific period or event, Bohemian Rhapsody, which charts the story of mega rock group Queen, doesn’t always hit the mark.

What it does do well, and this is largely thanks to Rami Malek’s superlatively-good performance as tortured creative genius Freddie Mercury, the band’s flamboyantly-charismatic lead singer, is deliver up a stellar love letter to a band that became known for big, anthemic, highly-emotional, crowd-immersive songs.

These songs, and pretty much all the jewels of Queen’s illustriously-large catalogue are featured in some form or another, most prominently at the recreation of their iconic Live Aid performance in 1985 which tops and spectacularly tails the film, strike an emotional chord with people and so it makes sense that they essentially form the film’s narrative framework.

Where this works is in creating a sense of mood and atmosphere, the kind of emotional touchpoints that work so well in concert and which create the heady sense of being part of something bigger than yourself.

It’s partly why people love bands so much – they engender a sense of time and place so potent and profound that one lyric or sliver of melody is enough to send a person hurtling back to those big markers in our lives which become inextricably linked with the music we are listening to at the time.

The writer, Anthony McCarten and director Bryan Singer of Bohemian Rhapsody, clearly understand this, liberally sprinkling the songs throughout, in many cases at major points in the band’s career where things were going well or not so well, the songs an amplification of the themes onscreen at the time.

Where it doesn’t work is essentially robbing the narrative of the depth that might have taken the film from merely good, and it is wondrously, transportively good in ways that leave you elevated and buoyed once you emerge from the cinema, to great.

For reasons that have as much to do with the length of time the film chooses to cover as the way the songs crop up and dominate scenes to the exclusion of all else – it makes sense; the songs are the things with which we have a deep and personal connection – ideas are thrown into the mix, cursorily or somewhat examined and discarded before we’ve even had time to draw breath.

That’s not to say they aren’t given due importance of some kind.

For instance, the tortured nature of Freddie’s relationship with his stern Parsi father (Ace Bhatti) is given a reasonable amount of time onscreen, although it is reduced to fractured scenes and an overuse of well-worn tropes.

Similarly we are given a window into Freddie’s dark and lonely life, a place enlivened by the concert performances which gave him vivacity and purpose and close friends like close friend and onetime wife Mary (Lucy Boynton) and his band family guitarist Brian May (Gwilym Lee), drummer Roger Taylor (Ben Hardy) and bass guitarist John Deacon (Joseph Mazzello), but which also lost its way in drugs, alcohol, endlessly partying and casual sex, particularly during his years with his personal manager and lover Paul Prenter, who gaslit his charge to the point where Freddie was isolated from everyone else in his life.

These and many other issues are given airtime and come with some hefty emotional baggage, again thanks to the depth and complexity of Malek’s portrayal, but they are also given short shrift too, almost glancing off the sides of the narrative before it moves remorselessly and yet feel-good engagingly on.

It means that Bohemian Rhapsody is a bright but shallow effervescent delight that gives you a chance to relive everything that Queen meant to so many, and does it brilliantly well, but which at the same time, disappears almost as quickly as it first appeared.

The pity with the overall approach here is that what it does, it does very well.

You would have to have a heart of concrete and a soul of solid granite not to swept up in the heady rise and rise of Queen when they were selling out concerts around the world, releasing music that was quirky and out of the usual musical ruts and yet emotionally accessible and meaningful to so many.

If you’re happy to leave the film solely in that space, and many will be including yours truly (who’s also enjoys in-depth, excoriating biopics too), Bohemian Rhapsody is a gilt-edged joy, elevated by Malek as Mercury, songs so luminously catchy you end up singing them inside, and later outside, with joy you thought long lost, and the final 20 minute or so recreation of the Live Aid performance that is exquisitely and moving well recreated.

Not all films have to be penetrating excursions into the tortured life of this or that celebrity, and nor should they be, since sometimes it’s simply enough to remember and glory in what was, especially if it’s something you lived through directly.

Where Bohemian Rhapsody probably errs is that it seems to want to be richer, darker and deeper, and hints it will go that way only to pull back, straddling two kinds of biopics and only doing justice to the one. (On this note, there is nothing wrong with just being an escapist, diversionary biopic; the “sin” of the film is probably simply attempting to be all things to all people.)

This will likely leave a sizable number of people feeling bereft and a little robbed, and in one sense you can understand where they’re coming from, but in the end Bohemian Rhapsody is designed primarily as an uplifting trip into yesteryear and you are likely best staying solely in that place and not wondering what is hinted at and might have been.