For something so big and catastrophic in its impact, losing someone you love to cancer is a remarkably intimate affair.

Admittedly it doesn’t feel that way at the time with so many decisions to be made, competing emotions to grapple with and lifechanging moments to get your head around, that you begin to feel as if it isn’t the biggest, most monstrous, all-consuming thing to have entered your life.

But dig down through all the tumult and emotional cacophony, all of which is wholly justified but nevertheless overwhelming and you come to that small, intimate place where all that matters is that you are losing someone you hold dear to a disease so insidious it cares nothing for your grief and gnawing sense of loss.

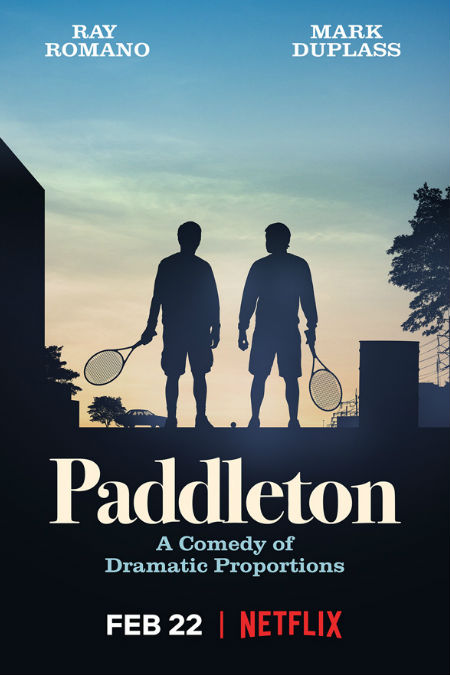

It’s in this place that Paddleton, an indie film with a big heart and an even greater sensitivity to the way a cancer diagnosis can upset the most treasures of status quo, sits sits quietly and unassumingly, telling its story of neighbours Michael Thompson (Mark Duplass) and Andy Freeman (Ray Romano) who are best friends and the centre of each other’s very small worlds.

Working dead end jobs that provide little in the way of professional or personal fulfilment and averse to the kind of small talk that routinely builds bonds between people, the two men, each quirky in their own way, spend their nights and weekends playing a variant of racquetball they created called Paddleton against the tin wall of old drive-in theatre, watching old badly-dubbed Kung fu movies and making pizzas.

There is little to no variation between the nights but neither Michael nor Andy care, happy to talk about their films, oddly-engaging topics of conversation that go nowhere but which amuse them, and to simply be in each other’s company.

It’s a small but idyllic existence … until, all of a sudden, it isn’t.

We find out that this rupture has already occurred right at the start of the film, where an understandably by-the-books doctor is delivering the bad news to Michael with Andy, who is confused throughout the film by a number of people as his friend’s partner, such is the close bond between the two.

In characteristic fashion, the two men trade quips and off-kilter observations, even making a game out of how bad the cancer might be.

The doctor may not understand why the two are being so playful with such a devastating diagnosis but you quickly discover that this opening scene is emblematic of the way Michael and Andy relate, with every situation viewed through a unique lens that people outside the friendship have no access to and usually can’t appreciate.

It’s a dynamic that Andy hangs onto tenaciously throughout the film which moves from the early diagnosis through to the two men trying to maintain business as usual through to them hitting the road to obtain the euthanasia drugs that will allow Michael to end his life while he is still well enough to do so.

While he is at peace with his decision as the quieter and more thoughtful of the two – though it later emerges in one of the film’s intensely-moving last scenes that this placid veneer hides a lot of unexpressed emotions – Andy is not, desperately trying to oneliner and quirkily observe his way through a crisis that has the capacity to completely blow a gigantic hole through his entire world.

For all that cataclysmic import, it is the quiet, small intimacy of the unfolding of Michael’s diagnosis and eventual death, and the way it affects Andy in ways he can’t even begin to admit, that drives this beautifully-nuanced film that has jokes and humourous observations aplenty but also an intense amount of heart and searing insight into the way something so big and underwhelming finds expression in the quietest and most heartrending of ways.

(image courtesy Netflix)

Driven by quietly-understated performances by both Duplass and Romano, Paddleton is a film that lives in the still moments between and within scenes, that only resorts to one emotionally-explosive scene that speaks less of dislocating anger than extreme, intense grief and loss, and which lets one scene flow into the another, with what sounds like authentic, real-life adlibbed dialogue and a willingness to let the day-by-day sit cheek-by-jowl unassumingly next to the anything but.

In that respect, it feels very real and true to anyone’s lived experience, acknowledging that while a cancer diagnosis is traumatic for everyone concerned (most obviously the one with the cancer although Andy makes it clear at one point that that does not invalidate what he is going through), much of the struggle to deal with it, whether you fight it or bow to the inevitable, takes places in the ordinary environs of the everyday.

It may feel catastrophically-world ending and for Andy at least it is – though the film ends on a note of nascent, slightly-awkward hope that leaves you smiling through your tears – but it is not a struggle that finds expression in big epic moments; rather it exists in all the small things that make life worth living, which for Michael and Andy are the nights filled with pizza, Kung fun films and Paddleton.

It’s that observation that invests Paddleton with so much affecting heart.

In fact, the film’s impact on you, and it is considerable, sneaks up on you, masked by nonsensical conversations, offhand observations and musings on all kinds of things including, most touchingly and most moving, in the one final major exchange between the two which centres on how Michael should haunt Andy.

It’s a conversation ripe with silliness but also, obviously an almost palpable and choking sense of something wonderful drawing to a close which both men meet, for the most part (but not entirely – see the close to final act), in a characteristically-offbeat fashion.

Quips and quirky views on life aside, Paddleton is ultimately a film that examines, with considerable honesty, heart and insight, what it feels like to confront the end of all things, at least as it applies to you, and how, against all expectations and lived-experience, this most horrifically life-altering of events takes place in the usual every day business of living, and sadly for all of us, dying.