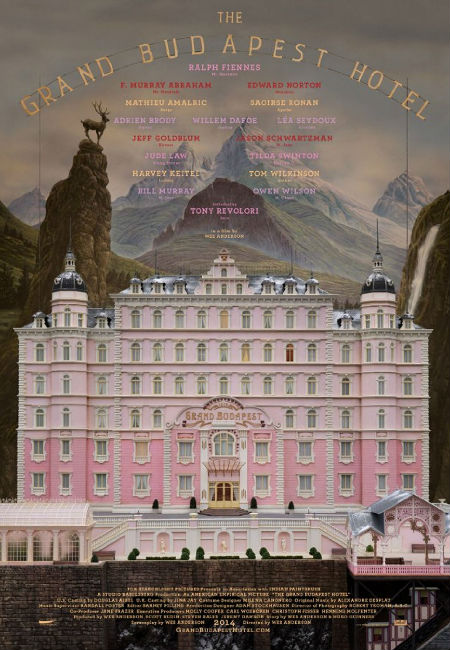

It would be tempting to call The Grand Budapest Hotel, writer/director Wes Anderson’s latest gleefully whimsical excursion into grand and imaginative storytelling, the icing on his creative cake, were it not not such an obvious reference to the pastries which are a recurring motif of the film.

And yet it’s almost impossible not to do that given the candy coated lunacy that suffuses the whole undertaking, a darkly-filled confection of slapstick comedy, artfully constructed yet wholly delightful and accessible wordplay and fantastical flights of fancy that somehow manage to co-exist quite happily within a reasonably linear and thoroughly entertaining narrative.

It is a master work that marries the visually rich almost-cartoonesque elements of previous movies like The Royal Tenenbaums (2001) and the emotionally resonant quirkiness of Moonrise Kingdom (2012) with sugary rich clever dialogue, twists and turns aplenty, some logical, some not, and characters that practically spring off the screen such is their contagious vivacity.

Chief among this panoply of deeply engaging characters is M.Gustave (Ralph Fiennes), the very epitome of a world class concierge, a man you suspect may be of humble origins given his ability to swiftly and amusingly move from buttery smooth upper crust articulation to more earthy street pronunciations.

He is a creature of impeccable taste and grooming who reigns over the imperial grandeur and luxurious decadence of The Grand Budapest Hotel in the fictitious Kingdom of Zubrowka, with an equal mix of fatherly love, evangelistic fervour and dictatorial control.

His is a world of every whim catered for, a continuous conveyor belt of indulgence that stretches from the sumptuously decorated lobby to the vast bedrooms of the many rich, vain, superficial, and yes blonde (“they’re always blonde”) old women who stay for “the season”, all of whom come to enjoy not just M. Gustave’s platonic attentions but his sexual ones as well.

The belle of this amusingly aged ball is undeniably Madame D. (Tilda Swinton), an obscenely wealthy lady from the city of Lutz, who dotes on him, and who on her prophetically-predicted passing, leaves a painting of incalculable value The Boy and Apple to M. Gustave as a sign of her eternal affection.

It is an affection shared most assuredly by the man who calls everyone from prison inmates to grand dames and thuggish almost-fascist soldiers “Darling” but you sense that his ardour of a far more practical nature, an end to a means and that his delight in being bequeathed the painting has more to do with the lifestyle it will afford than anything else.

Not that he is gauche enough, well not in polite company anyway, to say that out loud.

But when his adoring protege and The Grand Budapest Hotel‘s lobby boy in training Zero Moustafa (charming and accomplished newcomer Tony Revolori) suggest they abscond with the painting lest one of Madame D.’s avaricious children, chief among them desperate Dmitri (Adrien Brody), keep it for themslves, M. Gustave readily agrees.

And so begins a deliciously anarchic romp through the realms of war-threatened Zubrowka, which combines equal doses of Keystone Cops-ish physical comedy (M. Gustave and Zero’s flight on foot through the snow is a joy to behold), witty wordplay, and farcical yet oddly believable situations that delight the eye and cheer the soul.

Peppered with cameos by the Anderson faithful such as Bill Murray as a walrus moustache-adorned concierge, Jason Schwartman as a lazy concierge at a less glamourous ’60s incarnation of the hotel, and Edward Norton as a fastidiously careful member of the Lutz Police Militia, to mention but a few, The Grand Budapest Hotel‘s story is largely told by a much older Zero (who inherited M Gustave’s wealth and the hotel) to a man simply identified as The Author (Jude Law/Tom Wilkinson), a literary treasure of Zubrowka.

It is a story of a belle epoque world that as the older Zero quietly but sadly admits had probably disappeared before M. Gustave had even found his place in it, and one which the Author, his persona inspired by gifted Austrian writer Stefan Zweig, faithfully does his best to bring to life in all its inventive glory.

But it is Wes Anderson, in his first film to not directly focus on the concept of family (although a gathering of like minds does exist between M. Gustave, Zero and the love of his life, pastry maker Agatha played by Saoirse Ronan), that brings this bygone era to life with wit, whimsy and a healthy dose of evocative nostalgia for a world long vanished.

As with all his movies, it is a visual feast, a riot of bright colours, retro stylings and cartoon-ish landscapes which he invests with emotional depth and characters that though they often only appear on screen for a fraction of a scene come alive with all the fully-fleshed out joie de vivre you could ask of them.

The Grand Budapest Hotel rarely pauses for breath, content to run riotously on, dragging us happily along with it, a film that manages to tell a wholly engrossing start to finish tale while adding enough bells, whistles and verbal and stylistic flourishes to cater for a slew of lesser realised movies.

It is that rare cinematic creation – a film that is an absolute delight on every level, a resoundingly satisfying story that leaves you with a spring in your step, a pastry-smeared smile on your face and profound gratitude that men of rare artistic vision and whimsical imagination such as Wes Anderson exist in our reality-scarred world to bring us such wonderful, perfectly created treats.