If you are to believe the extremists of the world, morality is lived in bright well-defined technicolour, with no room for ambiguity or misinterpretation.

However, the reality is that while there are core principles that should be observed, much of them possessing a distinct Ten Commandments flavour, life is never quite as forgiving, continually muddying the waters, and turning the once-clear blacks and whites of moral certainty into the greys of real world living.

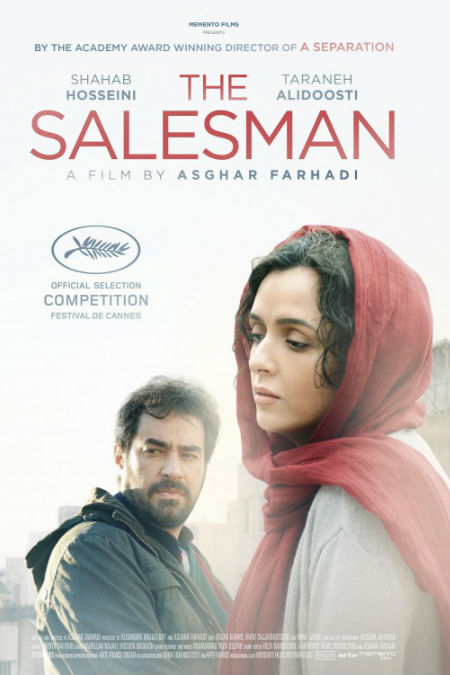

It’s in this invidious area of murky moral intent that an Iranian couple living in Tehran, Emad (Shahab Hosseini) and Rana (Taraneh Alidoosti) find themselves inhabiting, the former more than the latter, when the near-collapse of their apartment building sets in train a series of events that catches these two successful actors off guard.

Though it is clearly implied they are well used to the moral compromise and give-and-take necessary in a society where censorship and moral infuse every facet of life including justice and the arts, even they are unprepared for the ramifications of an attack on Rana in the new apartment they move to after they have to evacuate their old one in the dead of night.

Unaware that their apartment, which belongs to an acting friend Babak (Babak Karimi), once once leased to a prostitute – the neighbours simply infer this, pointing to her many acquaintances, all male – whose goods fill a much-needed room, Rana buzzes in a man she assumes to be her husband.

But the caller is not Emad, who has to stay behind after the final dress rehearsal of their troupe’s staging of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman (chosen no doubt because of its own agonising meditations on morality and what constitutes a well-lived life) to deal with censors, and Rana is attacked, severely injured, ans quite understandably traumatised to the point where she doesn’t want to be alone.

Rather than comfort his wife as you might expect, Emad turns inward, his previous bright, confident countenance giving away to reproach, anger and an obsession with finding the perpetrator that quickly turns from a do-it-yourself detective hunt to a vigilante-style attempt to bring about what he sees as a just and moral outcome, which is to make the person pay.

It’s at this point that Emad and Rana’s well-balanced life comes royally off the rails.

The genius of Iranian director (and the film’s screenwriter), Asghar Farhadi, who clearly means the film to be a veiled criticism of the way in which morality, whether religiously devised or not, can be corrupted despite the best of intentions, is that he lets this moral implosion develop in expertly nuanced small incremental steps.

Emad is never portrayed as a monster directly but as his search for the man who hurt his wife gathers pace, and he finds himself unable to take the matter to the police – Rana nixes that on the grounds that the police will see her as morally culpable in some way for the incident – he makes some increasingly rash and hurtful decisions, all of which leads to a decidedly morally questionable confrontation with the perpetrator.

While it is not a vigilante movie as such – Farhadi is far too insightful and careful with his narrative to craft anything so obnoxiously cumbersome – it does carry with it much of the morality that fuels those kinds of movies, a desire to see, not so much justice served and forgiveness given, as vengeance enacted.

Emad of course doesn’t see it in those terms, and it is only when Rana’s issues with an ultimatum that he pulls back from the precipice, well somewhat at least.

By then of course the damage is done, and it is becomes quite debatable who the greater monster is – Emad, who begins his crusade with the best of intentions to seek justice for his wife (even though he fails to show much if any empathy or kindness after her ordeal), the perpetrator, who is nothing like you expect him to be, or even possibly a society that though founded on venerated religious ideals, has now sunk into a legalistic shadow of its once idealistic self.

It is easy to why Farhadi earned his second Oscar statuette at this year’s Academy Awards (his first was A Separation in 2012) for The Salesman.

It expertly, and in way that intimately connects you to the two central characters, dissects the way in which morality can so often be skewed and misshapen for someone’s own purposes; it’s a dynamic that takes place on a societal and individual level and the use of Death of a Salesman clearly underlines the point that every society can fall prey to its twisted outcomes.

In Farhadi’s case the spotlight is quite clearly, though this is diffused by a script that never says this outright, on Iranian society and people like Emad who have been forced to take matters into their own hands by a system that simply does work like it was intended.

But it could just as equally be applied to any situation where morality has been presented as uncorruptably immutable and clearly set when it can so often be twisted into forms no one intended at the outset.

To be clear, The Salesman doesn’t meditate on the nature of right and wrong – it’s accepted naturally enough that assault, murder and a number of other human rights violations, large and small, are inviolable concepts – rather it examines the way in which their realisation can be tainted until all semblance of their original virtue is gone.

Emotionally powerful, so much so that you’re left reeling by the film’s finale which is both ambiguous and not all at once, The Salesman is a sobering, brilliantly-acted and directed rumination on the way our humanity, though never ever flawlessly lived out, can be so easily lost in the very act of seeking to redeem it.