Grief is the enemy of many things.

Forward momentum, a belief in a rosy future, creativity, laughter, renewal and rebirth, a sense that if you put one foot in front of the other, even just for a short while, it will lead somewhere meaningful.

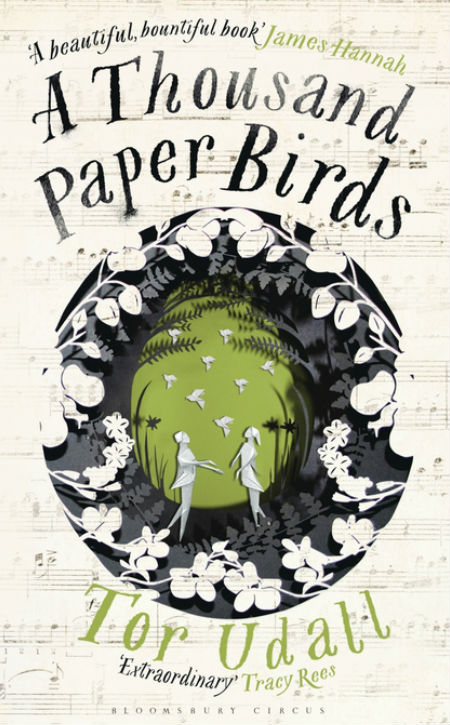

The exquisitely-wrought debut novel by Tor Udall, A Thousand Paper Birds, which draws its evocatively-poetic title from the origami art of one of its key characters, speaks to this enervating loss of life’s potential and hope in ways so eloquent and true that it will leave you gasping in recognition as each silken paragraph winds its way into your heart, soul and mind, and pretty much anywhere else that human experience deposits its hard-won self.

Centring on Jonah, a musician-turned-music teacher in his late thirties who has suffered the sudden and near-catastrophic loss of his wife to what appears to be vehicular suicide, A Thousand Paper Birds is a meditation on the way grief, a natural part of things, can so take hold that life has to fight very hard to gain any kind of useful foothold again.

That’s not to say this is a book so heavy it will sink through your side table with the weight of its musing; but it is intensely thoughtful and insightful about how the way grief, which the five stages tell us is supposed to be a clean and easy step-by-step process, is profoundly messy, disturbing and revelatory all at once.

“Outside the window, Kew Road is dappled in spring and passing people. The sky is in its rightful place, as are the tops of the trees he can see behind the wall of the botanical gardens. Inside the flat, the fridge is still stocked with milk, the crockery still red. The furniture hasn’t been moved, nor the streetlamps, or the bins on the pavement, but Jonah can no longer recognise this place. It is as if overnight the world has been rearranged.” (P. 6)

The book is written so beautifully that you find yourself stopping more often than not on a particular phrase and repeating it over and over just for the pleasure of hearing the artfully-arranged words roll off your tongue.

This is literature as poetry, but rather than feel remote and sucked dry of emotion, so well-worded and rarefied that there’s little left to relate to in the gritty confines of the everyday world, Udall’s poetic-stylings, her innately pleasing way of expressing just about everything, are accompanied by emotions so real and authentic, so precisely true and recognisable if you have ever suffered any kind of deep loss (I lost my dad last year and her depiction of grief is as real as it comes) you can’t help but connect with the way in which Jonah struggles to rejoin humanity’s ceaselessly headlong pell-mell rush through time.

It is testament to Udall’s gorgeous prose is that A Thousand Paper Birds never feels sad, for all its raw, emotional honesty, but beautiful and achingly alive.

In fact, for all the talk of being caught in the quicksand of loss and unable to grasp the possibility for change and renewal that crops up over and over whether you’re ready for it or not – it’s the nature of life and time that it will not, at least in terms of its very existence, be denied – the book actually speaks, more often than not, about the possibility of things once again growing and developing, shooting skyward rather than downward, no matter how everything feels when you’re mired deep in the soul-sucking torpor of grief.

What it does do is bring home the fact that life is complicated and prone to twisting back on itself, especially if you’re someone acutely attuned to its possibilities, as are Jonah, artist Chloe, park keeper Harry and 10-year-old Milly, that it’s not a simple matter of simply undoing a few missteps or uncertain decisions or mixed-up emotions, and moving on.

It is, in fact, really, gloriously, unnervingly messy but, and here’s that hope again, it is possible to lift yourself up and take a step or two somewhere new, and in your own time – thankfully A Thousand Paper Birds is wise enough to never make any of its insights prescriptive in any way – rejoin the human race.

Fittingly the novel is heavily set in and around London’s famous Kew Gardens, an expanse of natural wildness and domesticity devoted to humanity’s intricate relationship with flora where all four characters find the room to think, pause, ruminate and mourn, and ultimately, find the strength to move on when they’re ready.

It is very much the novel’s fifth character, and while the idea of a place as an additional character is often thrown around in earnestly hokey terms by authors and PR teams, in the case of Udall’s book, it is very real, and essential to where everybody is when the story opens and where they end up when it, quite regrettably, closes.

“He thinks about the different versions of a story crashing into each other; the battle over who is right and who is wrong. Both sides portray themselves as victims; both accuse the other of perpetrating. The intrepid adventure becomes a tale of pity. The page in Harry’s notebook is smudged with rubbings out.

“We covet happy endings. So why do we end up the authors of our own failings?” (P. 234)

A Thousand Paper Birds is all kinds of things at once, and often simultaneously.

Emotionally-authentic to the point where you can almost reach out and touch the palpability of Jonah’s overweening grief, Chloe’s disaffection and nascent hopefulness, Harry’s reluctance and regret and Milly’s garrulous happiness and aching sense of something missing, it is also magically beautiful in ways that will leave you sitting in quiet awe.

It’s mystical and hushed in giddy appreciation for the conjuring trick that is life and the human experience; but it’s grindingly real and able to articulate it in ways so perfectly true that you will want to quote it to anyone who will listen, and trust me, read out a paragraph and they will listen.

Udall’s powerfully, quietly triumphant book, is as real as it gets but it’s also hopefully alive in a way that makes sense of that inherent contradiction.

It’s one of those rare books that doesn’t tip too much one way or the other, that acknowledges the bad but looks out and up to the good, and expresses it all so richly and so beautifully, mindful at all times that life is nothing but a melding of all kinds of messiness, and that it is infinitely, gloriously rich even when it feels like it will never be that way again.