In this self-actualised age in which we live, we are sold the idea over and over that we can have anything we want if we just want it hard enough.

Kind of like wearing down the universe until it caves in and grants us undying happiness, peace, contentment, and possibly, a villa in the south of France.

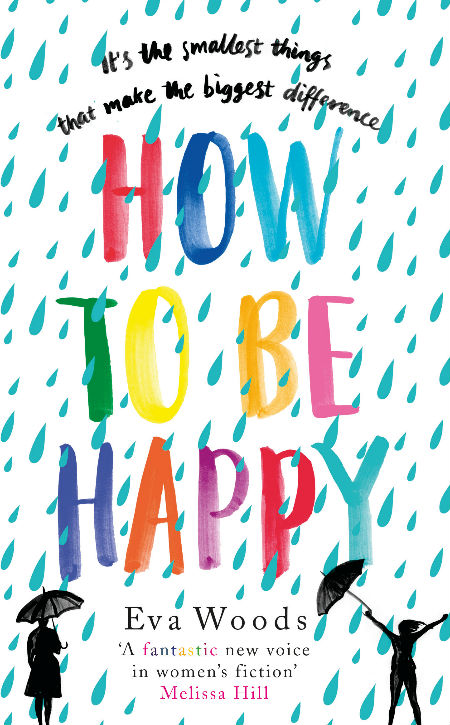

The truth is, and blessedly Eva Wood’s quirkily realistic tale of finding happiness where it appears there is none to be found, How to Be Happy / Something Like Happy (depending on where you live) acknowledges this head-on, is that life very rarely meets our demands, no matter how much we might want it to.

What it comes down in the end then is our attitude; much of life isn’t necessarily going to be our full and complete, and let’s be fair even partial liking at times, but it’s what we do with those grittily stark scenarios that defines the kind of life we’ll lead.

Now bear with me here – How to be Happy is blessedly not one of those books that serenades you with endlessly upbeat messages about staring life down with positivity and giddily upbeat chutzpah until it subsumes its more depressing elements and crueller instincts to your cheery, Pollyanna-ish frame of of mind.

“Annie turned to see who was interrupting. In the doorway of the dingy hospital office was a tall woman in all shades of the rainbow. Red shoes. Purple tights. A yellow dress, the colour of Sicilian lemons. A green beanie hat. Her amber jewellery glowed orange, and her eyes were a vivid blue. That array of colour shouldn’t have worked, but somehow it didn’t.” (P. 4)

Were that life was that simple and easily-shaped, a block of possibilities that happily yielded to your Tony Robbins mindset with nary a whisper of objection.

Alas, this is real life, and not a happy-clappy fantasy – ask Queen, they’ll tell you – and rising above can be a challenge of almost insurmountable proportions.

Just ask Annie Hebden, a council worker in London who works at a finance job she hates, lives in a grimy 10th floor flat that is a far cry from the flower-fringed house she occupied with her ex-husband who is not installed there with his new wife (someone once close to Annie which makes it even worse) and is mourning the death of her child and her mother’s early-onset slide into dementia.

She doesn’t have a lot to be happy about, and truthfully Annie isn’t, not even a little bit; Polly on the other hand, who Annie meets in the neurology ward of the hospital where her mum is being treated, is a force of carpe diem nature, determined to seize the best and brightest from every day, come what may.

The only snag for Polly? She’s dying of brain cancer and only has 100 days or so to live, the sort of prognosis that would send anyone into a tailspin, and in a nod to the grim realities of life, it definitely does to that to this bubbly whirlwind of colour and bravura at times, but Polly is obsessed with bending life to her demands, and to Annie’s jaundiced astonishment she pretty much almost always succeeds.

She takes Annie dancing in fountains. On the most dangerous rollercoaster in Europe. Convinces Annie to reconcile, with some amusingly strong arm tactics with people who have done her wrong (the list is long) and those caught in the collateral damage aftermath, and to rethink her entire approach to life.

Annie, of course, is having none of Polly’s go big, go large, go happy approach to life at first, convinced you can’t reshape life like that; but Polly is relentlessly, gloriously upbeat and together with her gay brother George (who’s sullen and cynical), Annie’s 22-year-old gay flatmate Costa and everyone Polly has ever known, and or just got to know (this is pretty much the entire hospital) sets about changing not just Annie’s life but the fate of the hospital, that of friends and family and even the homeless man in the hospital’s bus shelter.

It’s a joyous journey through the infinitely rewarding and uplifting possibilities of life, and it will have you smiling more than not, but Woods’ genius is in grounding this transformative tale, which has both a happy ending and an obviously not-happy one, in the brutality of day-to-day life.

How to be Happy never once assumes that life is your plaything, a complaint lump of clay to be molded as you see fit; even Polly, assailed by a dying, ever more decrepit body, has to accede to that point far more often than she’d like.

“Polly looked around the audience, the staff members crowding into the wings and the aisles of the theatre, and she was smiling, despite her exhaustion.

‘When I imagined where I might die, it wasn’t in Lewisham. It would have been on a tropical island somewhere, maybe in a tragic speedboat accident at the age of ninety.’ Laughter. ‘But now that it’s happening, I feel truly lucky. If I have to die, I can think of no better place to do it than here [the hospital], with these people taking care of me.” (p. 182)

What this sparkling novel does beautifully, and with great compassion and insight, some drawn from Woods own personal experience, is highlight the fact that life sucks but that doesn’t mean your experience of it has to suck too.

Much like Inside Out, Pixar’s gloriously rich to the complexities of life, is acknowledges that sadness and anger have a place in our lives, a necessary and important one, but it emphasises, in the most realistic way possible, that those emotions don’t have to be your default emotional setting, the defining characteristics of your life.

That’s even in the most dire of circumstances, and let’s face it, imminent death is pretty dire, not that Polly really wants to admit that, although circumstances dictate that she no longer has a choice in the matter.

The real joy of How to be Happy is its embrace of life’s good and bad, but its predilection for adopting a mindset that priorities little or big moments of happiness over simply letting the chasm of despair consume you.

You may not find your life changed as Annie does – although thankfully the changes are utter and absolute, with many unpalatable realities left in place – but you can adopt the 100 days approach which seeks to find the small and big joys in life such as baking a cake or going on that longed-for trip to the Bahamas.

Whatever it is, and again the novel is blessedly realistic about how this positive outlook can affect your life, you can change how you see life and thus how you live it, and if nothing else, and there is a great deal to recommend this gem of a book, that alone makes it worth the read.