If you look around at any given moment, on a world of towering buildings, fast trains and everything available at the touch of a button or a quick walk into a store bursting with products, it’s tempting to think that it’s all inviolably permanent.

We have enough dystopian literature around us that tells us it’s anything but; still, it looks strong, untouchable, always accessible and so we believe the lie, pushing thoughts of anything other than unending civilisation to the further reaches of our mind.

It’s comforting but does us no favours, which is why we need authors like Melissa Ferguson, an Australian, who we are told through her bio, is a “cancer-fighting scientist who loves to explore scientific possibilities.”

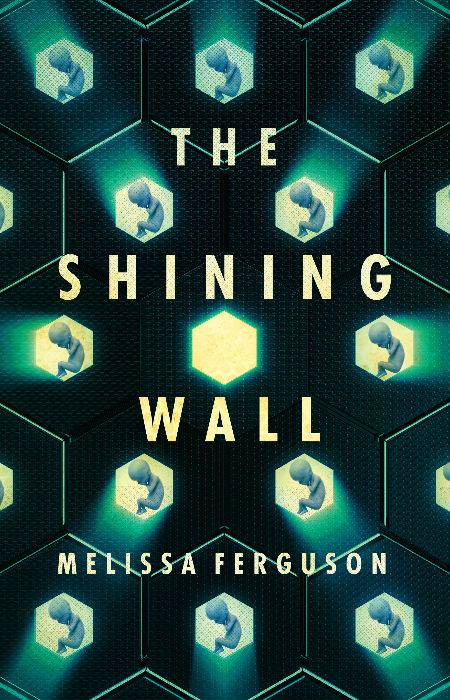

Seemingly unafraid to tackle the kinds of issues many of us tuck away where the light of hard truths can’t find it, Ferguson has poured her scientific knowledge and her raw, penetrating insights about the nature of humanity, into her brilliantly-good debut novel, The Shining Wall.

In just 295 tautly-told pages, we are introduced to a highly-possible future in which the “characters” of old – knowledge of our epoch seems scant with only our lingering and decaying possessions left as fractured and wholly incomplete evidence that we were ever there at all – have given way to a world of slums known as Demi-Settlements on the outside, indulged Citizens on the inside behind the titular shining walls, and those out in the wilds who are captive to a variant of extreme ideologies, the kind that flourish in the face of want and deprivation.

“Alida wished she had prepared some kind of speech or something. Would she look back one day and regret that she hadn’t made more of a ceremony of these last moments with Mum? Maybe if she could remember one of the religious stories Mum sometimes told. Even just a phrase. Alida’s mind was as blank as her credit chip. And then there were people waiting behind them to ditch their own dead.” (P. 5)

It’s a hard-scrabble world, unless you are one of the Plastic Faces inside the wall, some one million per city, who are coddled and looked after to within an inch of their carefully-moulded, highly-regimented lives by LeaderCorp, where inequality is rampant and where it’s not just the human beings are who situated along the perilous line of haves and have-nots.

Humanity, in its dubiously-evaluated, infinite wisdom has used its still-present though not equally-dispensed advanced technology, to resurrect the Neanderthals, or Neos as they are habitually-referred to, to act as grunt labour in everything from its factories to its security forces.

Seen as little more than fleshy robots with no feelings or intelligence, very much in line with now-outdated thinking about our evolutionary forebears, and at one time, contemporaries, the Neos are resources, and resources only, another utilitarian device for humanity to wield its misbegotten and misplace sense of superiority over.

But as with everything in life, what is assumed is not what is actually true, and the Neos, in this case security officer Shuqba and Ferrassie (and her unrequited admirer Amud) are as fully-formed and capable of love, intelligence and wise/poor decision-making as their sapien overlords, something that proves key in this impressively-told story.

The Shining Wall is an utterly-engaging tale, not simply because it shines a rather uncomfortable light on rampant injustice and economic inequality, societal ills that affect us today but carry on into the future, but because it does so with such insightful, affecting humanity.

Packed though it is with incisive messages, none of which are wielded with any kind of polemic clumsiness, and towards its thrilling but satisfying final act, edge-of-your-seat action, it remains first and foremost a story that focuses on what happens to people when society loses sight of the fact that they are people and treats them as easily-used and abused commodities.

We all know at our core that this kind of inequality is not sustainable, with history showing us again that empires always fall when they are founded on systems so hierarchical and manifestly unfair that only a few get to sit atop the shining wall of opportunity, but it is a lesson that it seems each generation, even those blighted by a world caught in ecological and societal free fall, have to sadly learn anew.

Ferguson fills The Shining Wall with these lessons at every turn but so beautifully embedded are they are in the stories of Alida, a young but determined woman from the Demi-Settlements and Shuqba, who defies her training to become more human that the Sapiens (or “little brains” as they pejoratively refer to their lords and masters behind their oblivious backs) , that we take them in anew, mulling over what happens to a society so unjust as the tide begins to turn, inevitably, against it.

“The Sapiens no longer had the power of numbers and she [Shuqba] no longer cared about Security Force protocol or upholding LeaderCorp’s laws. She was no longer their tool. Everything that had happened since she’d arrived in the city had proven Karain right. LeaderCorp was a corrupt slave-driving junta.” (P. 228)

The Shining Wall is that rare novel – one that has something vitally-important to say but which says it without hammering us over the head with a message which we would be likely to ignore were it not administered with a Mary Poppins-level spoonful of sugar.

Reading through the story, which captivates you from its emotionally-impactful first page through to its last sobering but fulfilling final words, is to take in a great deal, to have assumptions challenged and ideas provoked, to realise once again his perilous is the line that separates rack-and-ruin from prosperity, and to understand that one false step could lead to dystopian futures becoming the actual norm and not a literary concept.

But such is the strength and skill of Ferguson’s writing that The Shining Wall is also an exploration of the very best and worst of humanity, and that includes the Neos who are, in many ways, more human than we are and less tangled in some monstrous tangles of twisted morality, all wrapped up in a richly-spun story that is never less than utterly immersively, and consistently compelling.