At first glance, writing a wildly, hilariously satirical film about the death of one of the most brutal dictators of the twentieth history, and likely human history generally, would not seem like a first, best idea.

But then you’re not Armando Iannucci, the writer of The Thick of it and Veep, who penned the screenplay with David Schneider, Ian Martin and Peter Fellows, and the film you create and then direct to perfection, is not The Death of Stalin, his latest parodic masterpiece which it turns out, mines a period that is way more absurd than you might expect.

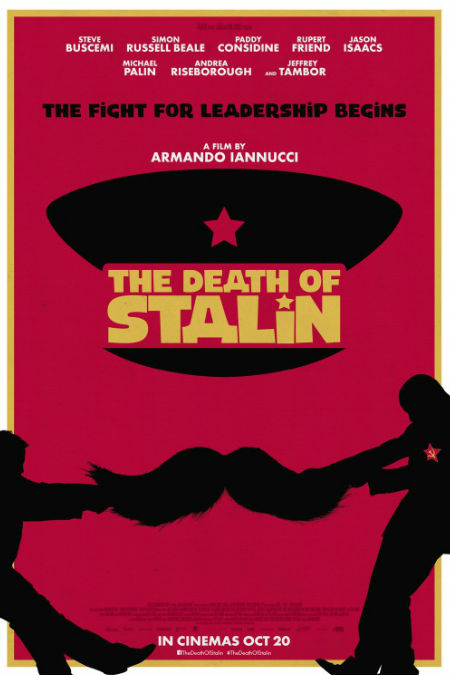

Starring some impressively heavyweight names including Steve Buscemi as Nikita Khrushchev, Jason Isaacs as Marshall Georgy Zhukov, Jeffrey Tambor as Georgy Malenkov as the Deputy General Secretary, and, of course Adrian McLoughlin as the titular tyrant, The Death of Stalin takes a true story that reveals much about Russia’s flawed and corrupted peoples’ revolution and how a once noble idea to be free of imperial tyranny simple result in the imposition of new more common, but no less deadly one.

What is so unashamedly brilliant about this typically-intelligent, devastatingly-insightful Iannucci creation, which brims with witty lines, lethal comebacks and unavoidable darkness, is that it doesn’t tip over into frivolous silliness at any point, rendering its satirical barbs, inert and dull.

Rather, the more farcical things become, and as Khrushchev, a ranking member of the Politburo, the ruling Communist Party’s highest decision-making body, and Simon Russell Beale as Lavrentiy Beria, brutal head of the repressive NKVD secret police, tussle for power, they become quite farcical indeed, the film keeps a sure and even footing, barely putting a foot, or word just as importantly wrong.

What many people won’t be aware of, since there is precious little about Stalin’s murderously paranoid regime that was even slightly funny, is how hilarious the events of his death were, but how, even more it underscored how the dictator’s virulent anti-semitism, mistrust of pretty much everyone, and heavy-handed rule played a significant role in his sudden demise.

When Stalin lay dying on the floor of his dacha in late February 1953 from a suspected brain aneurysm, no one dared to enter his rooms to which he had retreated as dinner and one of his favourite, ironically, American cowboy movies with his inner circle.

Under strict instructions that he was not to be disturbed once the doors to his private rooms were closed, his guards remained at their posts outside for almost a day before someone dared to enter the inner sanctum.

At that point Stalin wasn’t dead – his death didn’t come until 5 March – but his slow slide from the land of the living, and under his rule, the living were afraid to make a move lest they ended up on one of his infamous kill lists, was made all the more certain by the fact that it coincided with his anti-Semitic push against hundreds of Moscow’s most prominent doctors, many of whom were Jewish, and of of whom were locked up and being tortured in the NKVD’s holding cells and thus unable to make house calls to Stalin’s dacha.

In the midst of his lingering death, one which began with the dictator demanding a recording of a live classical music broadcast on Radio Moscow, setting in train a separate series of madcap, fear-generated events of a most absurd nature, the Politburo began scheming and planning for Stalin’s inevitable successor.

Initially it was Beria who emerged triumphant, the real power behind the throne of Malenkov, who for a week succeeded his old boss as Premier of the Soviet Union but he was soon out-manoeuvred by Khrushchev, man of humble origins from the Ukrainian/Russian border region who knew how to outsmart his rivals.

What all of this reveals, and Iannucci has admitted he had to tone some of the absurdity of these real-life events, is how once everyone stepped out from the fearfully-large shadow of Stalin, where free thinking was actively frowned upon, they felt emboldened to race for the levers of power with giddy abandon.

Absurdist it most certainly is, and Iannucci is content to mostly let the events of that momentous week stay ridiculously unadorned, but it shines a real and penetrating light on the dark nature of absolute power, a salient lesson when our once-vibrant democracies and world system founded on are not short of dictators and tyrants, and those vying to subvert carefully-constructed mechanisms of popularly-elected government.

The Death of Stalin is both an instructive history lesson and a riotously funny piece of political theatre, but more than that, it highlights, as only tautly-written, intelligent humour can do, how quickly once-great ideals, and the Russian Revolution was underpinned by some noble, if disastrously-executed ideals, can become nastily and destructively sullied, dragging some countries and people with them.

So while you’re laughing, and you will laugh a good deal at the inherent silliness of so many grown men resorting to such infantile antics to grab a morsel of power, it’s sobering to realise that in ways just as puerile and stupid that people these days in a wide variety of contexts are doing much the same.

The great tragedy is, and The Death of Stalin subtly but powerfully illuminates this truism is that absurd those the events may be, they reveal to an alarming degree how government, upon which so much of humanity’s welfare depends, is brought about by similar backroom machinations.

It mat may for grand, epic and thigh-slappingly funny theatre but it is also very serious with some dark and troubling, and at times, deadly consequences for those left to be governed by people who have exacted so much time and effort bringing about the lining of their own pockets of power.

But honestly, all this musing is for after-the-fact; for while The Death of Stalin doesn’t shy away from showing the darkness and hideous outworking of dictatorial government, and it’s all but inevitable messy succession struggles, it is gloriously, amazingly, wonderfully funny, filled with stinging bon mots and the wittiest of witty lines, delivered superbly by a stellar cast, such as that you will be recalling them in multitudinous abundance long after the cinema lights have come up.