When you love someone’s creation with the unvarnished innocence and enthusiasm of childhood, and yes, this can persist well into adulthood since it retains for perpetuity the shape and ardour with which it was formed, it’s hard to conceive of its creator as someone with raw, troubled humanity, in other words, as a real, living, breathing human being.

In our perfect mental mindmap of this person, everything is sweetness and light, their every move enshrouded with the same joy and liveliness they bring to their characters and the world they inhabit, and there is not a hint of sadness, longing or raw humanity.

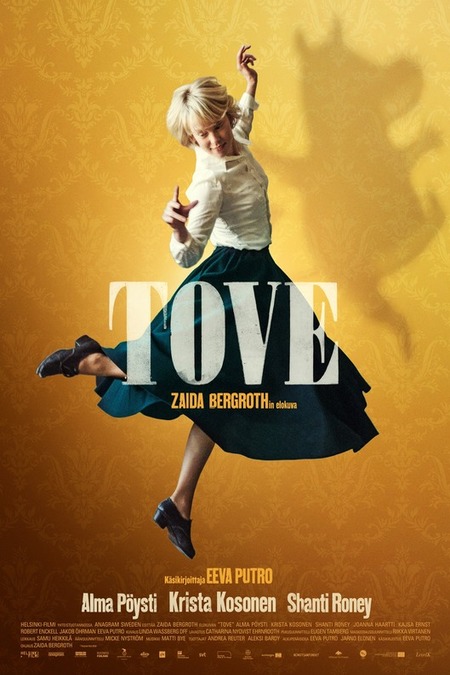

And while you might worry that a biography of the creator of such luminously untrammelled standing might tarnish their goodness in your eyes, the Zaida Bergroth-directed Tove, starring Alma Pöysti as Tove Jansson, the Swedish-speaking, Finnish creator of the much-loved Moomins, does triumphantly the opposite, bolstering Jansson as someone capable of so much wonder and thoughtfulness by letting be her beautiful, fallible self.

Set during the end of World War Two, and into the mid-Fifties when Jansson is coming to grips with what art means to her, and struggling to emerge from under the dominating shadow of mercurial, demanding sculptor father Viktor ‘Faffan’ Jansson (Robert Enckell), Tove is a adroit piece of filmmaking that affectingly balances Jansson’s quest for artistic realisation and fulfillment with her queer sexual identity which finds its voice when she meets larger-than-life theatre director Viveca Bandler (Krista Kosonen).

Living in a loft apartment without running water or heating – this doesn’t seem to bother the Bohemian sensibilities of Jansson who happily and messily creates, sleeps and eats in the same large open-plan space – Jansson simply wants the freedom to create art her way without her father’s constant disapproving presence.

Supported by her loving mother Signe ‘Ham’ Jansson (Kajsa Ernst), who does her best to ameliorate the constant tension between father and daughter – by way of contrast she and Tove’s brother Lasse (Wilhelm Enckell) work companionably side-by-side – Tove, for all her screw the establishment protestations, is keen to establish an art career in the more accepted realm of painting.

But while she does this, she is drawing and writing the story of the Moomins, a supportive family of hippopotamus-like characters who are trolls living in the aptly-named Moominvalley where they go on all kinds of magical adventures, loving and supporting each other and learning valuable life lessons along the way.

While many of us, this reviewer included, hold the Moomins tightly and with great affection in our hearts, and truth be told, Tove loved them too, with their presence a constant line running through the decade or so that the film covers, there is a considerable amount of angst on Jansson’s part about pursuing them as an artistic endeavour.

While she needs the money the Moomins bring in, she deems painting and the mainstream acceptance it brings, at least among the artistic community of which she is very much a part, to be true art and even towards the end of the film when the Moomins are a bona fide success, with plays, comic strips and books already circulating around the world, she laments to friends, painter Sam Vanni (Jakob Öhrman) and wife Maya (Eeva Putro) her failed status as a painting great.

Written with insightfulness and nuanced understanding by Eeva Putro, Tove observes that the creation of art in any form is not a linear or untroubled process, riven with the kind of angst non-artistic likely don’t even envisage being part of any kind of creation (their view is all bucolic fulfilment and creative bliss) and that it might end up altogether somewhere good and wonderful, which is certainly the case for Jansson, the journey there is not problem-free.

This is especially the case with her love life which has entangled in it, the aforementioned Vivica, who slept with a string of women so considerable that you can see Jansson reeling at the length and breadth of the list of past lovers, some of whom she awkwardly meets, and also dear, sweet Atos Wirtanen (Shanti Roney), a socialist politician in the Finnish parliament.

Jansson cares for both these people deeply but in entirely different ways and her struggle to come to grips with what matters to her most in the romantic sphere mirrors that which takes place in her artistic life where contrary indecisiveness is very much the order of the day.

The great joy of Tove, and it is a delight to watch from its quiet meandering narrative which belies a powerful, emotional punch through to its finely-realised period setting and Pöysti’s captivating performance as Jansson, is the way in which she brings humanity to the creator of the Moomins who for many has entered that halo-wrapped place in the pantheon of creators who can do wrong.

While it can be compelling and reassuring for some to leave their favourite creators in such a rarefied place, the truth is that there is a richness and power in finding out who they really are, because it can often inform how you view their creations for the better.

Some might argue this is not a good thing since the creation should be enjoyed separate from the creator, but when you watch Tove, and you see how meticulously, charmingly and honestly a light is shone on Jansson’s life, you come to appreciate how marvellously complex the genesis of the richly-layered Moomin characters are.

Tove reaffirms that no matter how highly you hold a creation aloft, that it comes always from a very human, often benignly flawed place and that by understanding who gave it life, you can appreciate its wonder, beauty and fun all the more.

Certainly that is the case with Jansson who comes across as a supremely thoughtful, deeply feeling and immensely talented person, someone as capable of writing a comic strip as painting breathtakingly beautiful art, but also a person who, like almost all of us, isn’t ever entirely happy with who she is, what she does and who she loves.

(Speaking of which watching her quietly meet the love of her life, Tuulikki Pietilä (Joanna Haartti) is done with such unhurried grace and touching understatement, that it will make you swoon with its appreciation of how the great and enduring things in life often arrive quite unspectacularly and without a grand entrance).

Far from robbing the Moomins of any childhood lustre, Tove burnishes them further, granting us rich and bolstering insight into the complex person of Tove Jansson, helping us to understand who she was, at least in part, why art mattered to her so much and why its creation was as much about fulfilment as inner conflict for her, and how uniquely wonderful it is that a place as uplifting good as Moominvalley came into place in the personally turbulent years of 1944 to about 1952 thanks to an artist who held so much promise and delivered in ways not even she saw coming.